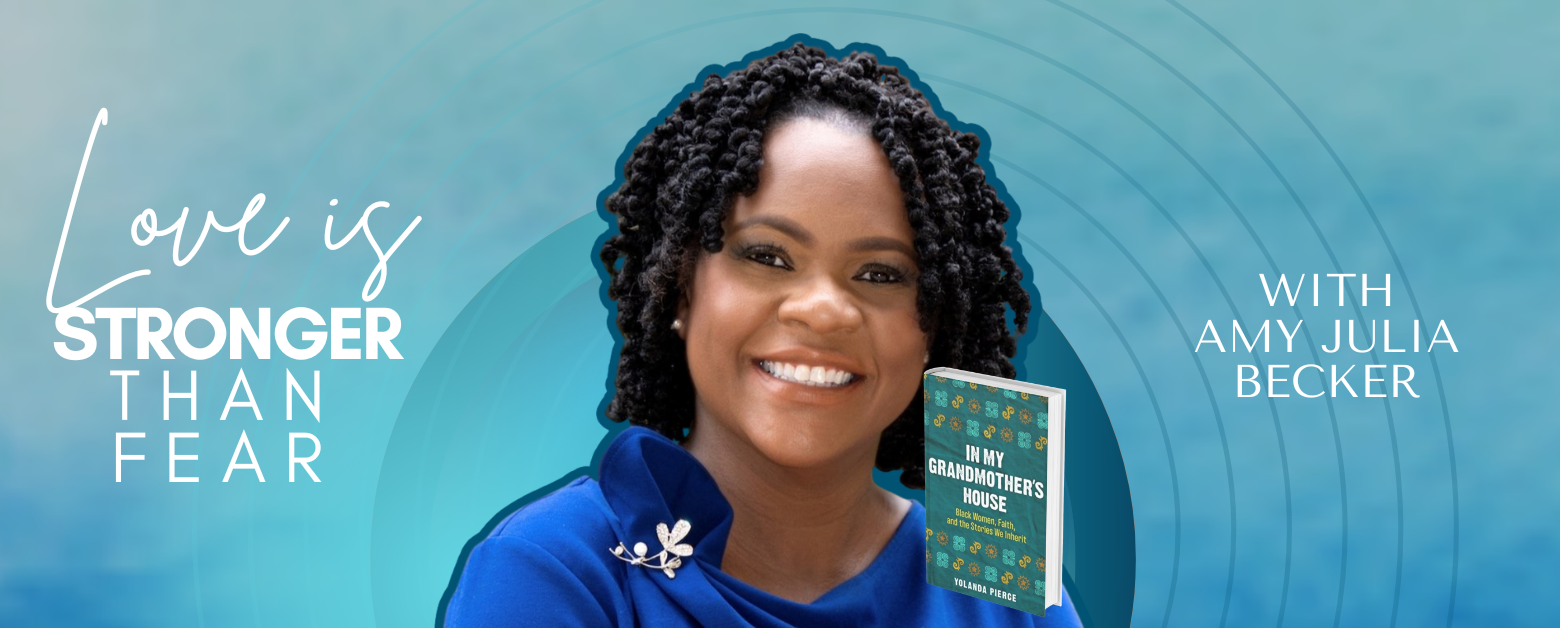

In an environment of deconstruction, how do we identify what needs to be torn down? And in the midst of the rubble, what are we rebuilding? Dr. Yolanda Pierce, author of In My Grandmother’s House, joins Amy Julia Becker for a conversation about:

- grandmother theology

- deconstructing Christian faith

- Black Jesus and unlearning racial hierarchies

- hope that something true and good and beautiful can be renewed and rebuilt within the church and within our world

Guest Bio:

“Yolanda Pierce, PhD, is a scholar, writer, womanist theologian, and accomplished administrator in higher education. She was appointed the Founding Director of the Center for African American Religious Life at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). And she currently serves as Professor and Dean of the Howard University School of Divinity.” Dr. Pierce will soon be Dean of Vanderbilt Divinity School.

Book: In My Grandmother’s House: Black Women, Faith, and the Stories We Inherit

Connect Online:

- Website: yolandapierce.com

- Twitter: @YNPierce

The transcript will be available within one business day on my website, and a video with closed captions will be available on my YouTube Channel.

Season 6 of the Love Is Stronger Than Fear podcast connects to themes in my latest book, To Be Made Well, which you can order here!

Note: This transcript is autogenerated using speech recognition software and does contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Yolanda (5s):

Within the Christian Church in particular, we are in, I think the best way I could really call it is an environment of deconstruction, which is tearing down, tearing apart and, and rightfully so. I think a lot of our tradition, a lot of our inherited values, as we have to rethink what it means to be people of faith. And that is important work. But for me, the work can’t stop at deconstruction because then you’re just left with this pile of rubble. What are you also building?

Amy Julia (39s):

Hi friends. I’m Amy Julia Becker, and this is Love is Stronger Than Fear, a podcast about pursuing hope and healing in the midst of personal pain and social division. And today I get to talk with Dr. Yolanda Pierce. Dr. Pierce is currently the dean of Howard Divinity School. She’s soon to be the dean of Vanderbilt Divinity School. And I got to know her initially when she was my professor at Princeton Seminary. So you can probably tell already that she is a scholar and a leader, but Dr. Pierce is also an author. She wrote a book called In My Grandmother’s House that we’re gonna talk about today. And she’s also a woman of deep faith who I really respect and admire for the ways in which she is holding on to the faith that she was given as a child and a young adult.

Amy Julia (1m 27s):

And also pushing some of the boundaries of that faith and thinking about what it means to pass it along to the next generation. I loved hearing her talk about what she calls grandmother theology. You’ll have to listen and learn what that means. And also her listening to her talk about black Jesus and what it meant for her to grow up within the racial hierarchy of our society, and yet also grow up with a deep understanding of the ways in which Jesus could be present to her and care for her. As a black woman, I love talking to her about our present era of deconstruction. For those of you who aren’t familiar with the term deconstruction, that’s something that a lot of people within the Christian Church in the West are talking about, a deconstruction of the Christian faith.

Amy Julia (2m 13s):

And Dr. Pierce talked about how important it is that while we are deconstructing, while we are tearing down the structures of our faith, traditions that have been oppressive and unjust and incomplete, rather than standing amidst the rubble and walking away to really ask whether something true and good and beautiful can be renewed and rebuilt within the church and within our world. Dr. Pierce is a rebuild, and I think that’s ultimately why I was just so grateful to talk with her today. And I think you’ll also really enjoy what she has to say. Oh, and I forgot to mention Yolanda. Dr. Pierce uses a big word a lot in this conversation.

Amy Julia (2m 55s):

The word is soteriology and what it means is the doctrine of salvation. Those are kind of other big religious words. So really when you’re thinking about from a religious perspective, how does someone get saved or rescued or delivered from sin, from death, from themselves, et cetera, how, how do we think about that from a religious perspective? That’s what soteriology is. So if you’re just wondering, as you go into this podcast and you hear that word thrown around, I wanted to give you a little bit of a cliff note since most of you who are listening here did not go to seminary like I did with Dr. Pierce.

Amy Julia (3m 35s):

All right, thanks so much. And now on to our conversation. I am here today with Dr. Yolanda Pierce, who is currently the dean of Howard University School of Divinity. But I just learned is also heading to Vanderbilt, so that’s pretty exciting. I’m also here because Dr. Pierce is the author of In My Grandmother’s House, black Women Faith and the Stories we Inherit. And As It Happens, she also was my professor in one of, if not my very favorite class when I was back many years ago as a student in Princeton Seminary. It was a faith and literature class, which I really, really loved.

Amy Julia (4m 16s):

So Dr. Pierce, I am so excited to see you and I just wanna thank you for being here today.

Yolanda (4m 20s):

Thank you so much. I am so excited to be here.

Amy Julia (4m 25s):

Well, so this book that you’ve written called In My Grandmother’s House, when I was reading the preface of it, I underlined that you called it a work of grandmother theology. And I just wanted to ask you to explain what you mean by grandmother theology, cuz I thought that might give us a little bit of your story and your grandmother’s role in your life and kind of how you got to the point of writing this book.

Yolanda (4m 48s):

Thank you. That’s a great question. So by training, I’m a womanist theologian and that’s an academic field, particularly for black women working in theology who work at the intersections of race and class and culture and all the, all the ways that you can think about intersectionality. But what I was most interested in, I think in that conversation, right, in that womanist conversation was about how in fact we talk across generations. I was raised by my grandparents, that is the privilege of a lifetime to be raised by grandparents.

Yolanda (5m 30s):

And so I was interested in what I was learning about faith, what I was inheriting about my own faith, not just from the generation right before me, right, my mother, my father, but from my grandparents, from the elders, from the older women in my community. So I come from a tradition in which we have an ecclesial office called the church mother. And while there’s no particular age requirement, these tend to be women in their seventies, eighties, and on these women, ye they, they wield a lot of power in our church. And so I was thinking about how these older women, despite not being trained in the way that you were trained, in the way that I was trained in terms of theological education, but living the faith, right?

Yolanda (6m 24s):

And so then I started thinking about this grandmother theology, which I’m just using as a way to talk about how we do theology through the generations, how narrative is passed from generation to generation, what legacy we wanna leave the next generation. But the impossibility, I think, of doing this work without a cross-generational conversation.

Amy Julia (6m 49s):

And one of the things I loved about your book was the way that you were both challenging some of the assumptions that your fore bears kind of brought to the table and yet really honoring them at the same time. And I just thought, gosh, so many of us right now could just learn from the way in which you didn’t say, well, because I honor you, I believe exactly what you’ve always believed. And yet you also didn’t say you are outdated and you don’t understand what it means to be a contemporary American or to have progressive values or whatever it is. And I thought that the story of Mother Johnson in your church, as she had comments to make about your appearance, could you tell that story and maybe talk a little bit about this balance of both honoring and challenging what you’re being given by those, you know, older generations?

Yolanda (7m 42s):

So I’ll say that within the Christian Church in particular, we are in, I think the best way I could really call it is an environment of deconstruction. Yes. Which is tearing down, tearing apart. And, and rightfully so. I think a lot of our tradition, a lot of our inherited values as we have to rethink what it means to be people of faith. And that is important work. But for me, the work can’t stop at deconstruction because then you’re just left with this pile of rubble. What are you also building? And so that’s really what I’m trying to respond to. There are traditions in which I was raised, there was a certain kind of legalism and conservatism there.

Yolanda (8m 29s):

There were things that I learned growing up that no longer a part of my faith, no longer a part of my values, I have to let them go because they are not life giving for me. And so one of the stories I share about Mother Johnson and some of the other mothers of the church is that they were certainly very fixated on our bodies as young women, as teenagers, what we wore, what we didn’t wear, how long our skirts were, the certain kind of policing of the body that has just really been a longstanding tradition in many religious communities. I wanted to just leave that behind and say, you know, that that, that’s just ridiculous.

Yolanda (9m 12s):

That’s what that generation of women did. They were just ridiculously concerned about what you wear and and how you present yourself. But the older I get, and then I became a mother, what I discovered is that we really need the gift of grace, the gift of grace to both allow ourselves space to accept what from our traditions we wanna retain what is life giving, what is still loving for us, and what are the things that we have to let go. I learned that these church mothers, even if their methodology was flawed, what they were trying to do was to protect me from the predators that we know exist within the church.

Yolanda (9m 58s):

And we know the predators that exist outside of the church. And so for this 13 year old girl or 15 year old girl, they were policing me, not in a way simply to say you’re a bad girl if you wear these skirts, but they were policing me in a way to say, we care about your safety. Those were the only tools that they had. Now I can say here, you know, generations later, I have other tools, but I have to have grace for women who loved me enough to wanna protect me, who loved me and cherished me enough to wanna admit that there were people who could do me harm even in this safe space of the sanctuary and that they wanted me to survive.

Yolanda (10m 44s):

And the grace I have for that is to accept that that was a act and demonstration of their love, even as I have to leave behind some of the legalism, right? And so we have to walk that balance in terms of our traditions. What do we inherit? What do we wanna keep, what do we accept as just a gift and a demonstration of their grace and God’s grace? And how do we build from the very things that we deconstruct? Because it’s not enough to just tear down. We have to be also in the work of actively reengaging and rebuilding something from that foundation.

Amy Julia (11m 21s):

Yeah. And I love the way you do. I mean, you told the story beautifully, just carry with you, okay, I’m not carrying with you the rules about the clothes I have to wear, but I’m, but I’m also not rejecting you or your theological care for me. Right. Or your grace. And, and so there is still a foundation of grace and care, even if there’s not, even if we’ve knocked down the rules about the skirt you’re wearing. And I just think that’s really beautiful.

Yolanda (11m 52s):

And what I really am trying to think demonstrate by using story and storytelling and what we would call narrative theology, is to suggest that I didn’t know enough about their stories to really understand why they approached, how they interpreted scripture, how they interpreted text, how they lived in this environment. There were stories that they never told me. There are some stories that they will never tell, right? Yeah, yeah. But once I understood that and acknowledged that we are the product of the things and experiences that have happened to us. And so for this particular group of women, descendants of sharecroppers who found their way here in Brooklyn, New York, but you know, throughout the country where these descendants of sharecroppers and enslaved people landed that their experiences, their stories, what had happened to them, what vulnerabilities of their own body they may have endured, had everything to do with how they then were reacting to me.

Yolanda (12m 55s):

And so that’s where the grace comes in and why the sharing of stories is incredibly important to me.

Amy Julia (13m 1s):

Yeah. This is just a line from that chapter you wrote that you kind of received this message, even though no one ever said it out loud, cover yourself because this world eats up little black girls and I want to spare you from some of the pain I know all too well. And the fact that you were able to get to the point of seeing what could just simply feel like oppressive legalism, seeing that as a desire to protect and care for you and keep you from pain just, I think speaks again to that process that so many people are going through right now, especially Christians as far as deconstruction. But again, wanting, I love what you’re saying about the building and, and retaining whatever is good and right and true about a foundation.

Amy Julia (13m 47s):

Obviously there are things even that seem kind of foundational that are being questioned right now and perhaps need to be turned into rubble. But that doesn’t mean there’s no foundation and it also doesn’t mean that we can’t rebuild. And that kind of brings me one of the other things that you write about as far as your grandmother in particularly, I’m gonna, these are just two quotations about your grandmother. One, she did not introduce me to religion. She gave me Jesus. And then two, she told me that Jesus consistently did three things, healed people, told stories and fed people. And that is all she as a follower of Jesus had to do in order to live a life pleasing to God. And I just was so taken by this person of your grandmother in terms of not of giving you Jesus.

Amy Julia (14m 32s):

And you also write about giving you black Jesus in particular, which maybe is something we could touch on, but also just that three things, heal, tell, stories, feed. And I would just wondered if you could talk again a little bit more about what it was that she was able to give you and what you’ve been able to build upon in terms of your own faith these days and what that looks like.

Yolanda (14m 56s):

I remember going to college in huge, huge main library on the campus. And this was literally back in the day when you were still actually looking up books, you know, using the, the Dewey decimal system. And, and, and there was an entire floor devoted to religion, right? Books and texts and tones about religion. And it was my first time actually thinking about how complicated religion was because I grew up with a grandmother who made the simplicity of faith so beautiful and so attractive to me.

Yolanda (15m 35s):

She fed people constantly. She told stories and she listened to other people’s stories and she visited the sick and shut in. And that was an expectation of our community. And, and that she said was what it meant to follow Jesus. So I just thought, okay, well this is easy enough. And it wasn’t until later that I really sort of encountered the complexity of it. But in that beauty, in that simplicity, what she was really introducing me to was that there is a difference between the structures and the systems of religious belief and what it meant for her to be an active follower of Jesus.

Yolanda (16m 18s):

This was a woman who had no formal education, had never finished high school, neither she nor my grandfather had ever finished high school. And what they knew and understood about who God is, was so real and so tangible. It was simple. And yet it encompassed everything. It was closer to what I as a scholar now really think about as cosmology more even than theology, which is that God was everywhere in our home. She was talking to Jesus in the kitchen as she was making biscuits. We were singing hymns in the house as we were cleaning up to get ready to receive company. That’s just where Jesus was everywhere.

Yolanda (16m 60s):

And so simplicity, I return to again and again. There are complicated issues in our faith. Denominations break up over issues of soteriology or baptismal formulas or what we believe about the eschaton, right? There are whole denominations, whole churches, whole other religious traditions born out of the minutia of how we kind of do this theological engagement. But I learned something about the essence of a God who loves a God, who cares, A God who needs you to have sweet tea and biscuits because that’s what you do when you love people.

Yolanda (17m 40s):

You, you feed them, you attend to their needs, their physical needs, their their, their day-to-day realities. And so I was learning something very powerful that later on I would have a whole theological framework influenced by writers like, you know, James Cone, you know, to to, to Luther, to Calvin, to Dolores Williams. But before I had ever encountered that, I had a praying grandmother and that really shaped and changed everything for me.

Amy Julia (18m 10s):

I love that so much, and I am curious to hear both as someone who has your particular story and you have, you know, a young daughter, 20 something daughter of your own. You are working with students who are presumably a lot of them in their twenties, and we have all this data, you know, kind of sociological data saying that this generation is leaving the church behind. Like whether that’s deconstruction or they never even grew up with it to begin with and aren’t that interested. And I know there are all sorts of sociological, you know, factors that play into this generation. Both, I think doing some really good work of asking questions and also what may end up being some really hard sad things for our nation if we come abandon faith altogether.

Amy Julia (18m 59s):

You know, and again, I don’t mean to say everyone should just go back to church, but I do wanna say, oh, this, the, the beauty you just described, that simplicity of understanding that a God loves you and will guide you and be with you both in a, you know, ephemeral way and also in the tangible reality of a praying grandmother. All of that, like, I want so badly to give that to my children and to this younger generation. So as you talk about and think about deconstruction and rebuilding, like what, what do you think, what do you think is going on right now and is there any hope for that rebuilding to happen again?

Amy Julia (19m 39s):

I’d just love to hear a little bit about what you’re seeing and what you think we might do to carry forward the faith that you’re describing, the one of a grandmother who says, feed the people, show up to the people who are sick and, you know, know that God loves you.

Yolanda (19m 55s):

So I love the question because I do work with 20 somethings all day, every day, and they give me a tremendous amount of hope. I think that I’m very fortunate to have a profession where I’m really engaged with the lives and the minds of the next generation of leaders at every level, but certainly religious leadership. What I’m seeing on the ground is that people don’t find joy, affirmation, connection in many of our formal structures that we call religious. They don’t necessarily wanna be in church as in the building.

Yolanda (20m 35s):

And many of them have been wounded by these institutions and by people who claim a religious identity. And we have to talk about that. We have to talk about those wounds. We have to talk about our failures. We have to talk about how religion and its theology has been used to hurt and to harm. But what gives me hope is that many of them have never abandoned spiritual practice. And that’s something we don’t talk a lot about. We, all of the data is about where people go. Do they go to church or do they not go to church or even what they believe? Do they believe in God or do they not believe in God?

Yolanda (21m 15s):

But I’m actually interested in practice, which is, as someone who grew up in the Pentecostal tradition, what do you do with your body? What, what do you do with your hands? What, what, what do you do? Not just what do you believe and think, but what do you do? And I think this generation gives me hope because they still care about spiritual practice and it just doesn’t take place inside of churches. Right? As someone who’s been deeply involved with the Black Lives Matter movement broadly, and especially here in Washington dc I think about the prayers at the beginning of marches and rallies, but they’re not being led by the minister. They’re not even being led by someone like me who might be wearing like my clergy collar or something like that.

Yolanda (21m 60s):

It, it’s the, it’s the 19 year old who has no formal Sunday school, doesn’t have the quote unquote language, but, but before the rally begins or the march begins, they, they stop because they realize this is a sacred moment. And so they pause. It doesn’t sound like the prayer that we’re used to, but it’s still prayer. And so I guess what I want us to really talk about and engage with, as we often talk about the decline as the church is to really say, but where is that deep rich spirituality embodied practice growing? And it may in fact not be our church buildings anymore.

Yolanda (22m 43s):

It may be the streets, it may be the rallies, it may be at protests. It, it may be when these young people are choosing to sit in at the, the courthouse, right? It, it may be these young folks in Tennessee who are like, we’re gonna shut down this legislative session. Right? When we start seeing that as the powerful reaction of what faith can do and what faith is, then we stop worrying about whether young people are religious and we really start engaging with the practices of justice, right? So if God calls us to do justice and these young people are doing justice, can we see that as religious practice?

Yolanda (23m 27s):

Yes. So that’s where my hope is. Hmm.

Amy Julia (23m 30s):

Yeah. And as a, I love the idea of religious practice, but also, again, whether it’s strengthening a foundation or rebuilding, you know, a structure that one of the things you write about, and this has been true to my experience as well, is going from kind of a privatized understanding of Jesus as a personal savior, which is not untrue, but is certainly incomplete, right? In terms of this bigger work that God is doing of mercy and justice and bringing truth and goodness into the world. And so not focusing quite so much on who is saved and what is hell, and you know, these, these questions, but rather like going back again to that, you know, what does it mean to feed the people?

Amy Julia (24m 15s):

And, and yes, to do that in my own kitchen, but also to think about the ways in which our structures and society are built to feed the people or to bring justice in terms of whether that’s representation or healthcare. Right? So I’m curious, again, if you could just tell a little bit of your own story in making that mo move from more of the privatized and worried about who’s saved and who’s not to a space of seeing something like protesting as an, an act of faith, as an act of religious practice.

Yolanda (24m 52s):

So that’s exactly, I think where I was trying to go, like most people, I grew up with what I stole to this day called the pocket Jesus rate of a very kind of privatized religion, personal faith, and, and, and devotional life. And that is a wonderful thing, and that is something that is still a very rich thing in my own life. But, but as I was considering this idea of salvation where we’re not saved, we are not safe, we are not whole if other people are incomplete or unsafe. Right? Or not saved. And, and so I had often heard that sociologically, it’s the story of Nicodemus asking Jesus, what must I do to be saved?

Yolanda (25m 39s):

Right? And, and that was a very narrow and restrictive definition of salvation that I had been exposed to in my early life, which is that if you believe these things, you say these things, you go get baptized, then you and Jesus are fine. Well, okay, but what about these other 7 billion people in the world? And not in a way of, I need all of these people to just learn about the Jesus in the way that I know Jesus. But am I caring about their safety? Am I caring about whether they are whole, whether they are well, whether they are healed? And those questions are the questions. This is, again, back to my grandmother’s Jesus, do, do you have food to eat when, when Jesus encounters people again and again and heals them, right?

Yolanda (26m 29s):

And, and does it make a big production of it? Just take up your bed and walk. You’re, you’re, you’re healed. That was the substance of ministry. That healing of the body, that healthcare, that being well in the body is absolutely crucial for functioning. So what we would say is hungry children can’t learn. And so we want schools where food should just be free because hungry children need to eat before they can learn. And so I started thinking about those real material needs that people have as being the way that we can really talk about wholeness and wellness and salvation, or as I suggest, an understanding of soteriology that is rooted and grounded in safety.

Yolanda (27m 15s):

Is the woman who is being battered by her spouse, is she safe? That’s the question we need to ask before we ask some sociological question about what happens in the eschaton? Will she meet Jesus? Will she go to heaven or hell, she’s living in hell. And so the question of her safety and her wholeness and her wellbeing, that’s the question we get to ask in this lifetime. And so those are the questions that, that are consuming me as I’m really trying to use my womanist framework to ask a different set of theological questions without negating the personal intimate salvific qualities of the crucified Jesus, who is a part of my tradition.

Yolanda (28m 2s):

And I still love that, but it can’t stop at the foot of the cross.

Amy Julia (28m 7s):

Well, and you write, this is about midway through the book, true salvation and healing for the soul are only possible when love overshadows fear, which is a great, you know, for this podcast, love is stronger than Fear is the name of the podcast. So only possible when love overshadows fear, when we embrace God’s saving work more out of a love for our neighbor than out of fear of hell and damnation, which I think is also speaking to that motivation. First of all, I want you to know safety and a sense of being saved, safe and saved right now for all the people who are living in those experiences of hell. Whether that’s physical or emotional or spiritual, you know, all those places.

Amy Julia (28m 49s):

And second of all, being motivated by love rather than fear in our own lives and in our world. And we do see, I think so much that emerges out of fear in our day-to-day, whether that’s, again, on the personal level, the anxiety that we are all experiencing around so many different things, or on a, on a much broader level, whether that’s, you know, fear of just what’s gonna happen in the future and getting things wrong and fear of other people not liking me. But just when our posture shifts from one of fear to one of love, I do think it can, can truly be a really, it’s a really healing, healing work.

Amy Julia (29m 34s):

Another thing you said you wrote was about a student who you really wanted to kind of, you wanted to give her all the answers and tell her all the reasons why she didn’t have to walk away from the church, essentially. But I think you basically decided not to, you just to sit with her. And you wrote, there’s a silence that is healing. And I wanted to just talk a little bit about that, the place for silence in healing. And again, the way, and I think there’s a, there’s a love in that silence as well in, in how you describe it. So could you just talk a little bit about, well, really, you can ping off of anything I just said. Cause I talked for a while. Thank you.

Yolanda (30m 12s):

No, no, I, I love that. My inclination as I think both a scholar, but also as, as a teacher, is that we love to talk and we love to explain things, and we love to teach. I love to teach. This is one of my joys and, and hopefully one of my gifts. And so of course over the years I’ve had students come to me with, with problems big and small per personal and, and, and academic. And my inclination is, is to solve, the problem is, is to figure it out, is to talk it through. I’m learning that sometimes people don’t need you to say anything at all.

Yolanda (30m 53s):

I’m learning about the beauty of silence. It is the healing of silence. It is the fact that whatever they say later for seven days job’s, friends sat with him in silence as a gesture of, I am present and I am here with you. The greatest thing that a theologian can say is, I don’t know. I don’t have all the answers. I, I’m, I’m doing theology and I’m learning theology, but I can’t ever expect to know the fullness of this God talk. And so I’m learning about that, about how to be with people, particularly around grief and grieving as, as someone who’s experienced grief and, and loss and, and the death of loved ones.

Yolanda (31m 43s):

The worst thing were the people who had things to say, but they were so cliched that they were actually actively harmful. They wanted to say something. And, and I get that they were well-meaning, but the things that they actually said were, were hurtful and harmful to me. And I remember the people who simply hugged me or held my hand and just sat with me as if to say, I don’t have the right things to say. What, what do you say to someone when a child dies? What do you say to someone when they, they, they have lost a parent? What do you say to, to the grieving widow?

Yolanda (32m 23s):

What, what do you say to the people who’ve experienced all of the atrocities of life? Sometimes you say nothing, and that is a healing gesture. That is a loving gesture, but that’s also a gesture of humility. Mm. I don’t have the answers. I can’t make this better for you. I can’t make this right. I can’t heal the sick. I can’t raise the dead. I can’t in this moment do the things that I wanna do, but I can sit with you. And I had a student where I, I wanted to, to say to her, no, no, no, come back to church. No, no, no. That was just one thing that happened over there. Church isn’t like that.

Yolanda (33m 3s):

And we, and, and something stopped me to simply say, even if all of those things that I was going to suggest were true, that the moment called for me to simply be silent. And it’s to encourage people to say, sometimes we just have to sit in that silence. And that is the most healing and loving thing that we can do.

Amy Julia (33m 24s):

Yeah, I love that. And I think also of how words can be a way of deflecting that, of, of ending the moment instead of saying, this is right now, the pain you’re experiencing feels endless. And I will sit there with you in it even if we don’t have a defined point. And of course there might be, and we might be the ones who carry that hope that that will not, you know, endure forever. But to be able to stay in that uncomfortable and undefined place of pain, I agree, is not only an aspect of healing, but takes just that deep humility. I have another question that

Yolanda (34m 3s):

You, oh, go ahead. Uncomfortable. Oh, it’s this, it’s this word uncomfortable because I think that’s exactly right. The speaker is trying to make himself or herself feel more comfortable, totally like, oh, well, you know, I’m so sorry, but this is, God has a plan and, you know, and they’re actually just trying to make themselves feel better. They’re actually not, in fact comforting the person who is grieving or the person who is wounded. And so we have to learn how to be uncomfortable in the silence. We have to learn how to sit in a space that feels like it, it doesn’t feel good. And there are no answers here. I don’t know how it will even conclude. It feels uncertain.

Yolanda (34m 44s):

That’s where faith actually shows up. Faith shows up in the doubt and the uncertainty and feeling uncomfortable, like not having any answers. That’s where God can do God’s work.

Amy Julia (34m 56s):

I, I agree. Yes, it is, and this is, so this, in some ways, to me, this links, my next question links up because of the, on a broader level, right? This is happening for individuals who are walking away from churches or who are experiencing that pain and grief of recognizing whether that’s actual direct abuse that’s been happening in churches, or even just really questioning some of what seemed like foundational beliefs, those types of things. But then there’s also, on this broader level in terms of church structures, there’s what we’ve been talking about at least publicly for the past couple years, the rise of white Christian nationalism, which again, has a long history, but has become this thing that’s being talked about and is very strange, right?

Amy Julia (35m 50s):

To embed, and this has been true again, for generations, but to embed a politics of hatred and oppression with a gospel of grace and love, right? That’s, that’s confusing, that’s hard. And you write about, and I know many people who are in this same position of saying, okay, I wanna be a part of a multiracial, a multiethnic church community because I believe that that is ultimately what God wants to do. God wants to bring us together. God wants to actually have every tribe and every nation, you know, in one, not one humanity in the sense that there’s nothing different about us, but in fact that there’s like a glorious diversity to who we are and what we bring. And yet also finding yourself in that context and saying, I have to walk away.

Amy Julia (36m 32s):

This is from your book. I still fear that the multiracial church movement simply replicates racist hierarchies, patterning itself after the white supremacist society in which it is lodged. And my question for you is, I think most of the listeners of this podcast are white, and most of us would like to be a part of dismantling and disrupting white supremacist structures and systems within the church and outside of it. But I’m wondering if you have any thoughts as someone who has said, I can’t stay here. Like, how does that disruption happen? How do we participate in making those spaces different? Like what, what needs, what needs to shift

Yolanda (37m 11s):

It? It’s a hard question because the answer is so big. Yeah. Which is that so much has to change. I share the story of a chi of being a child who grew up in a household where the pictures on the wall were pictures of black people, of course, but particularly black Jesus. Yeah. So in a lot of African American homes, we have pictures of Martin Luther King pictures of Malcolm Xes and like cultural heroes. These are religious heroes, but like in a lot of just religious households, you have pictures of Jesus or representations of Jesus or the Last Supper, or you know, whatever kind of religious art.

Yolanda (37m 52s):

Well, the religious art in my household was a picture of black Jesus. Now, how my grandparents born and raised in the south got this picture, I do not know. All I know is, is that I understood that that was a representation of Jesus. And this image had brown skin and the crown of thorns, he had very curly, textured hair. And that black Jesus looked like the black people in my neighborhood and the black people in my church, and the black people in my family. And so I just thought that’s what Jesus looked like. And, you know, just went on about my business. It wasn’t actually until I got to college and then traveled the world that I understood most representations of Jesus were white.

Yolanda (38m 38s):

Hmm. I talk about that because my grandparents gave me a powerful gift. I did not have to unlearn white supremacist practices of representations of Jesus as having blue eyes and having blonde hair, because given where he was born, that wasn’t likely. I didn’t have to unlearn this idea that Jesus was white, or everything about the church was white. Because what I saw was a representation of me. That is such a powerful tool because if we really truly talk about the Imago day, right?

Yolanda (39m 22s):

The idea that we are made in the image and likeness of God, then that little black girl growing up in Brooklyn, New York thought, of course, of course I’m a representation of God. Look at this picture. It looks like, you know, my uncle and I say that as one of the tools for how we can undo, unlearn white nationalist practices within Christianity, because that’s actually what it is. It’s about dismantling, unlearning, literally tearing down icons.

Yolanda (40m 2s):

That’s really hard work. People don’t want to give up. And here, I don’t mean actual physical representations of Jesus, but they don’t want to give up their sense of privilege. Meaning that somehow Jesus is more on their side than on someone else’s side. That, that, that somehow Jesus loves Americans more than Jesus loves Rwandan, right? Yeah. And the evidence of Jesus’ love is our prosperity and our money and the riches, right? The, the unlearning is actually harder than the learning.

Yolanda (40m 43s):

Hmm. And, and that is what makes this conversation about white supremacy, Christian nationalism, really, really difficult is because we have to unlearn racial ideologies, racial hierarchies, the ways in which we connote tangible financial success with us somehow being more blessed, more highly favored of God. We would have to dismantle all of this. People are in that process. I think there are people of goodwill who are trying to do that work, but it takes a very long time. It takes people acknowledging their privilege.

Yolanda (41m 26s):

That’s step one. Okay. So people do that, but the dismantling of their privilege much, much harder to do. So I think I was really very fortunate that I didn’t have to unlearn some things because unlearning is much harder than learning. I’m h is there hope? Sometimes. Yeah, sometimes Great. Because again, as somebody who educates younger folk, I said, okay, well they’re, they’re on the right track. But I also know that for me, it was a well thought out decision to say, even as I am called to this work, this dismantling work, this unlearning work, this helping us to think about the, the ways in which white supremacist practices have harmed us within the Christian Church.

Yolanda (42m 21s):

I’m, I’m called to do this work, but I also knew that I needed a space that was safe and that was loving for me. Hmm. And I was not finding that in this multicultural, multiracial church that at its root was still sort of practicing these kinds of same hierarchies. And so, so here’s a perfect example. I stopped singing songs about Jesus watching me white as snow. I grew up with hymn. I love hymns. To this day, I’m so old school, I, I love the hymns of the church, but there’s some things that I had to stop singing because those things were reinforcing this kind of racial hierarchy.

Yolanda (43m 10s):

That, that somehow, even saying that this must be washed, whiter than snow was the way in which we still use language of whiteness and lightness to equal that which is of God and darkness and blackness. And so not a leap then to black people as something that is apart from God. And so I had to stop singing even songs of the church that I loved, right? I had to really start saying to myself that the dismantling of these practices is work. Even as much as that work is, I won’t, I won’t sing those songs.

Yolanda (43m 55s):

I I won’t use those particular verses. I won’t reinforce agenda hierarchy by only referring to God as he, and that I’m making these as active choices to say that if I’m living into the kingdom, right, the, the, the kin folk, the kin of God, that I actually have to do that, certainly with the language that as a first and an important step to doing this work.

Amy Julia (44m 24s):

I think a lot about how language shape reflects reality and shapes reality. And I, I, I think a lot about that around issues related to disability, because we have all these terms and they keep changing. And I, I think that’s in some point in some ways because we just haven’t gotten comfortable with the idea of disability, or not the idea, the reality of disability that honestly will come to each of us in various ways, but still goes back to that place of discomfort. And one of the ways where I’ve been doing the same thing as you said, certainly when it comes to gender and race, but also when it comes to making, to being too quick to draw conclusions about disability and healing and wholeness from stories of disability in the scriptures, when you know, Jesus will heal a blind person.

Amy Julia (45m 18s):

And we will use language in our hymns again of, you know, I once was blind and now I see, and again, there might be some theological truth here that’s really important and good to explore. I don’t think we need to throw away the stories of Jesus doing the, that healing. But when we use it really fastly and can therefore put a person who is blind in the category of not as whole or close to Jesus as I am, right? Then we have lost, we’ve lost the whole, we’ve lost the thread, we’ve lost the message, and, and we’ve separated ourselves. And I think there’s some parallels there in terms of some of the work that you’re doing and have needed to do. And they’re all, they’re all related to, again, going back to that place of what does it mean to be motivated by love, to go back to a foundation of a simple but foundational truth, right?

Amy Julia (46m 9s):

About who we are and created in the imago day and connected to Jesus through caring for one another. And when we can keep returning to those foundations, I do think it allows us to build something that is stable and strong. And I guess this kind of brings me to my last question, and maybe you’ve already answered it, but one of the things you write again, is that black women are among the most faithful and religious Americans by any measure, measure. And there is, I think, a heartbeat to this book that on the one hand explains why that is. And yet also asks the question, how can that be in light of not only the oppression and abuse that black women have experienced throughout the generations from, you know, a white supremacist society, but even within the church itself.

Amy Julia (47m 1s):

But, you know, in all of these different ways, like why are black women among the most faithful and religious Americans by any measure? And, and again, like what might that, what might that have to say to people like me, you know, who have experienced so much more privilege and, and yet who also would say, yeah, I want that faith, I want that, I want your grandmother’s faith too. You know,

Yolanda (47m 26s):

That’s the question, trust me, that I try to answer almost every single day. It’s, it’s the, it’s a question of Mary, the how can this be? Mm. Right? Which was the question that Mary asked when the angel says, oh, by the way, she’s like, how can this be? So black women remain deeply engaged by every measure measure of religiosity, whether that is church attendance, whether that is giving, whether that is just the, the showing up. And, and I kept asking why. Right? I, I was asking that of myself like, what am I doing? I’m still showing up. Right? And I was certainly asking that of others around me.

Yolanda (48m 9s):

I I’m asking that as what it means to live as a black woman in the richest country and the world. And yet I and other black women, and I know so many who fear maternal outcomes, that that black women are three times more likely to die in childbirth in the United States, right. In 2023 than they’re white counterparts, even accounting for income and, and education. And, and what does it mean that I know black women with, with PhDs from the finest schools in the nation who have the best jobs in the country? And they say to me, I’m afraid that if I am in distress, that a doctor won’t care for me and might let me die.

Yolanda (48m 58s):

And, and the question for me is how do you continue to believe in God in the middle of all of this? Yeah. And the only answer, and, and it’s the one that I come to again and again, and, and it seems almost so simplistic, but it truly is the only answer that I have, is that we find something within the person of who Jesus is that draws us in so close that we’re not willing to let it go. I have to say, for me, it is the faith that I know would’ve sustained by ancestors as they crossed the Atlantic ocean and the hold of a slave ship.

Yolanda (49m 42s):

I’m just not willing to yield that faith, the faith that allowed them to survive that and enslavement and sharecropping and, and Jim Crow and, and, and the civil rights that that faith, I’m not willing to concede that it belongs to me. It is my heart’s song. And so because of that, I’m still trying to hold onto it even when it doesn’t make sense. And I think that’s the case for many other black women. It doesn’t necessarily have to make sense. I return again and again to the image of Jesus as friend, not as Savior, not as Lord, not reinforcing some kind of military hierarchy where Jesus is the general and, and where soldiers in the army that, that language for me personally is, is not life giving.

Yolanda (50m 32s):

I, I’m not a soldier. I’m not killing anyone. I’m not in an army, but, but the Jesus of, of being a friend, the, the Jesus who walks with me, sits with me, talks with me, cares about my material, need the way that I care about my friends, the, the Jesus who shows up in the kitchen, the Jesus who, when, when you are afraid at night, is there to comfort you, that Jesus I won’t let go of. And so I think that for many black women, the sense of a God who is present and who is near, who doesn’t demand our obedience and acquiescence as if we’re soldiers, but who, because of the friendship and love that God demonstrates, calls us to God’s self.

Yolanda (51m 24s):

That’s, that’s why we stay. That that is why we continue to believe not a God out there, but a God present close with the loving, tender, kindness of a friend.

Amy Julia (51m 36s):

And there is a sense in which amen to your description of that is bearing witness to the God who sits in the silence and who sits in that uncomfortable place and says, I’m with you again and again and again. And that I love the ways that you just both connected that to Jesus as friend and also to the generations of women and men, but women who have carried that insistence on the loving presence of God, even in the times and places and years, decades, you know, centuries that don’t make sense, that there’s still something that is deeper and broader and wider that we can return to and hold on to.

Amy Julia (52m 21s):

And going back to just that initial conversation we had about reconstruction that can provide a, a different, or a renewed, I guess is a better way of saying it, foundation to build on for the future. Well, Dr. Pierce, thank you so much for being here today. Thank you. Thank you for your book. Thank you so much. Yeah, I love it. Glad to have

Yolanda (52m 42s):

You. It’s been just a pleasure to have the conversation with you.

Amy Julia (52m 48s):

Thanks as always, for listening to this episode of Love is Stronger Than Fear. I will remind you that there are no advertisements on this podcast. There is no fancy marketing plan that is coming all out alongside it. So we rely on you to spread the word. And that happens every time you share this podcast. Every time you rate it or review it, it changes something in the algorithm so that a Apple and Spotify and all those other places tell more people that this podcast exists. So I’m gonna ask you to do that, just to give other people a heads up about this conversation if you feel like it might benefit or encourage them. Please also feel free to reach out to me.

Amy Julia (53m 29s):

I love hearing from you. My email is Amy Julia Becker writer gmail.com. As always, I wanna thank Jake Hanson for editing the podcast and Amber Beery, my social media coordinator for doing all the things that she needs to do to make sure that this happens. Finally, as you go into your day today, I hope you will carry with you the peace that comes from believing that love is stronger than fear.

Learn more with Amy Julia:

- To Be Made Well: An Invitation to Wholeness, Healing, and Hope

- S5 E12 | Racism: Can Learning History Bring Healing? with Lisa Sharon Harper

- S6 E17 | Questions for a Life Worth Living with Matt Croasmun

If you haven’t already, you can subscribe to receive regular updates and news. You can also follow me on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Pinterest, YouTube, and Goodreads, and you can subscribe to my Love Is Stronger Than Fear podcast on your favorite podcast platforms.