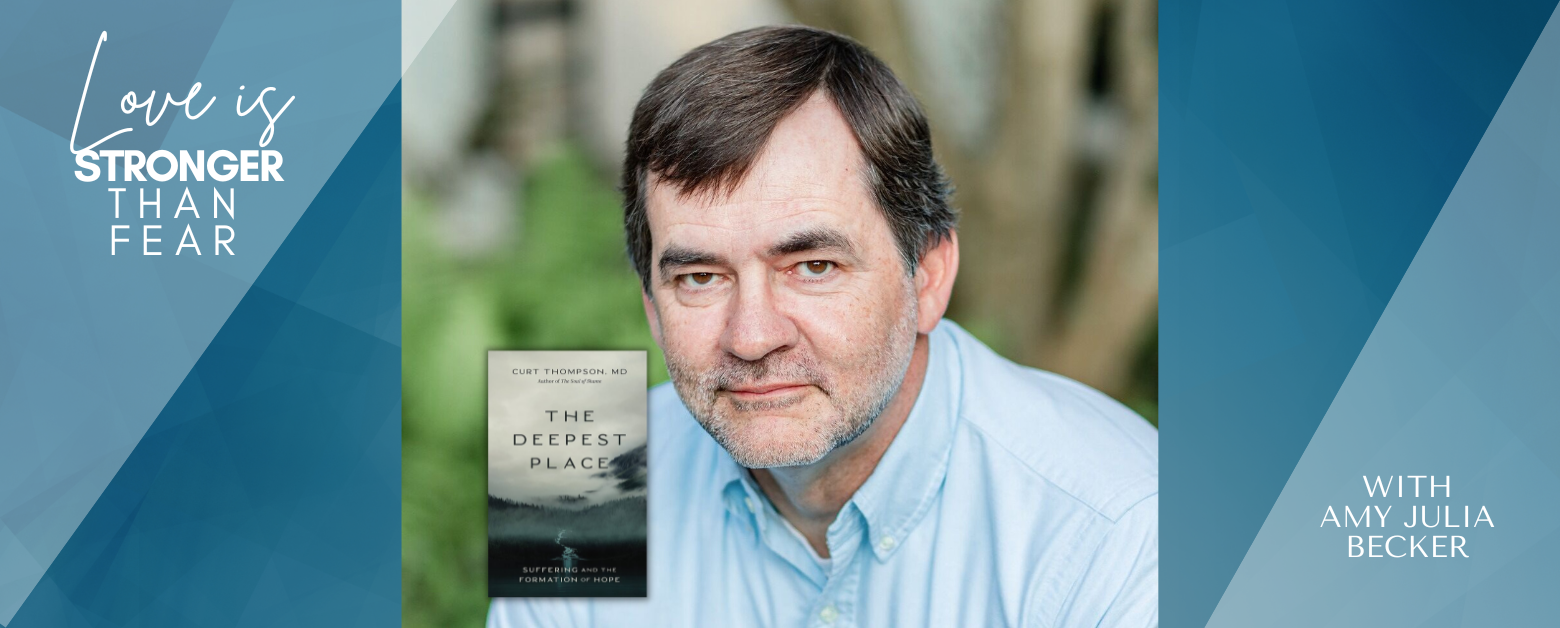

How do we show up for each other in the midst of pain? Is it possible to hope when we’re suffering? Psychiatrist Curt Thompson, author of The Deepest Place, joins Amy Julia Becker to talk about:

- How to identify the denial and shame we’ve connected to suffering

- How to form durable hope in the darkest places

- How to help a friend in the midst of suffering

Guest Bio:

“Inspired by deep compassion for others and informed from a Christian perspective, psychiatrist Curt Thompson shares fresh insights and practical applications for developing more authentic relationships and fully experiencing our deepest longing: to be known. He helps people process their longings, grief, identity, purpose, perspective of God, and perspective of humanity, inviting them to engage more authentically with their own stories and their relationships. Only then can they feel truly known and connected and live into the meaningful reality they desire to create. Curt and his wife, Phyllis, live outside of Washington DC and have two adult children.”

Connect Online:

- Website: curtthompsonmd.com

- Instagram: @curtthompsonmd

- Facebook: @CurtThompsonMD

- Twitter: @curt_thompsonmd

On the Podcast:

- The Deepest Place: Suffering and the Formation of Hope

- Amy Julia’s book: To Be Made Well: An Invitation to Wholeness, Healing, and Hope

- Hope Heals Camp

- Hebrews 12:1-3

- The Bible Project

- Genesis 2

- Genesis: The Story We Haven’t Heard by Paul Borgman

YouTube Channel: video with closed captions

Season 7 of the Love Is Stronger Than Fear podcast connects to themes in my latest book, To Be Made Well, which you can order here! Learn more about my writing and speaking at amyjuliabecker.com.

Note: This transcript is autogenerated using speech recognition software and does contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Amy Julia (5s):

Sometimes we feel like we tell the story of hurt and loss in our lives over and over again, and we wonder whether it will ever get better, whether we’ll ever have a new story to tell for anything like me. Maybe you even feel embarrassed to keep returning to the same problems, the same losses. Today I’m talking with psychiatrist Curt Thompson, about how Suffering can move us towards hope. And one of the most significant things that I took away from this conversation was the importance of repeating our stories, our in the presence of compassionate listeners who are willing to sit with us and hear it again and again until the Healing is complete.

Amy Julia (48s):

I’m Amy Julia Becker, and this is Love is Stronger Than. Fear. I’m so glad you’re here today for a conversation about Suffering and hope and healing and how we show up for each other in the midst of pain and how God shows up for us. I am here today with Dr. Curt Thompson and I, Dr. Thompson. Just wanna say, welcome to Love is Stronger Than Fear. We’re really, really excited to have you here.

Curt (1m 16s):

Amy Julia, it is a pleasure to be with you. I’ve been looking forward to this for some time, ever since I heard that we were gonna be doing this together. And so it’s an honor. I’m, I’m really thrilled to be with you, so thanks for having me on.

Amy Julia (1m 30s):

Well, you’re very welcome. And I’m gonna tell listeners what you and I have already talked about before we hit record, which is that I think our point of connection is Hope Heals Camp, and I don’t know that anyone will see the video of this, but I’m wearing my Hope Heals sweatshirt just to honor that reality. And I thought, you know, this book that we’re here to really talk about today, The Deepest Place is about hope and it’s about suffering. And so I really felt like that point of connection for us, even though we haven’t been at Hope Hills at the same time, we’ve both been in this camp experience, which some listeners will be familiar with, but others will not, in which there are all sorts of people who are experiencing pretty profound suffering and who are being, I guess, exhorted to hold onto hope without being exhorted to deny or dismiss their suffering.

Amy Julia (2m 33s):

And so I just thought maybe we could start there, because again, that’s a place where we have, you know, been connected at least through other people, is just like, could you talk about your own, I mean, give us a little bit of your background, but also like, how did you get to Hope Hill’s Camp and how does that experience, like, does that link to, in your own mind, like the work that you’ve done in this book, The Deepest Place. I’d just love to hear about that.

Curt (3m 3s):

Yeah. Well, my, my background is I was born and raised in Ohio. I was the youngest of four sons. My parents were in their forties when my brothers and my brothers were 18, 16, and 11 when I was born. Hmm. My father died when I was 17. I have lost all three of those brothers to cancer. Wow. I have been married for 37 years as of two days ago. Congratulations. Yeah, thank you. We have a daughter who’s 33 and a son who is 30. And all, all those things that I’ve just named have been extraordinarily formative for me.

Curt (3m 44s):

I grew up in a, in what, what we would call an evangelical Quaker tradition of spiritual Formation. Yeah. That look on your face is the same look that I get in me like, huh, how do we, what, wait, how do you connect those dots, please? So that’s, that’s a story in of itself. But was a, I I would say is, is a significant part of all that is good and rich about my life is because of that, because of that community. And then I, I, I, you know, went to a small Christian liberal arts school off to medical school and then residency training. That again, is also another story about how psychiatry, I, I, I tell people, I think Jesus has found me in a number of different ways over the years.

Curt (4m 27s):

One of the ways that he found me was through psychiatry. The psychiatry found me and not the other way around. And so I, I am grateful. I, I, I can’t believe that I get paid to do what I do and I don’t deserve my life. And this book emerged. I, I’ve written three other previous works that have one having to do with neuroscience and spiritual Formation. One having to do with shame, which is, in my sense, the primary affective state that is our, you know, leads to our undoing. The third work was on how longing and beauty in the context of vulnerable community really are a response to the violence of shame.

Curt (5m 11s):

That is, you know, not just in small ways, but in large ways kind of devouring us and has been devouring us. We, we Christians would say from the beginning Yeah. Or attempting to, attempting to devour, because all of this, all this, this notion of longing and beauty and presence to respond to violence shows up in the person of life, death, resurrection, ascension of Jesus And. that then brings us to this last work, this most recent work on shame. And I’ll just say a word about hope Heals camp to, to this regard. Because anybody, if you, if you have a pulse, you suffer. Hmm.

Curt (5m 51s):

For those of us in the West, for most of us in the West, if, if, if our listeners are here, like I, I don’t, I don’t believe suffer, I, I can’t remember say, then I would say it is probably the case that you have enough accessories in your life to protect you from yourself, such that that’s the only reason you think you don’t. There will always be something, there’s some part of us that suffers and we do all kinds of things to avoid it. And we’ve been doing this from the very beginning of time. This is not a new, this is not a new thing for us. One of the things that the pandemic did was it pulled the curtain back on our ultimate inability to avoid it. Right. It just kind of pulled the curtain back and there we are and, and we’re exposed to ourselves is what we, we weren’t just exposed to a virus, we were exposed to ourselves.

Curt (6m 33s):

And one of the things that hope, heal camp, hope Heals camp does, when you said at that camp, we are exhorted to hope in the middle of hard things. One of the beautiful things about it is that when we, when we think about that, we think, oh, I, I’m to be exhorted is I’m, I’m, I’m told something right? I am, I hear words that say, Curt, you, you should be hopeful. And I’m like, great. That, and a cup of coffee does what for me. Yeah. But the thing that happens at this camp is that people have embodied encounters with other people who care for them in ways that they’ve never been cared for, who attuned to them in ways that have never been attuned to who celebrate with them, all the while acknowledging the reality of their pain.

Curt (7m 24s):

We’re not pretending that this is not here. I mean, this is like, this is the news of the gospel, right. With crucifixion. God is saying, I’m not gonna pretend that the world is a pain-free place in play. In fact, I’m gonna wade right into it and put it on myself, and I’m gonna carry it. I’m gonna be with you in this space. And one of the things that we, that we talk about, I, I try to recognize and like the whole notion of hope in and of itself, we often don’t think about it until we’re in trouble. Hmm. And then I think, oh, I, I now, I, I need some hope because I’m in trouble when the reality is Amy Julia is that we actually employ hope all day every day.

Curt (8m 5s):

We just don’t know that we’re doing it. I hope that my car starts now. I don’t think that I’m hoping my car starts, but I go with the anticipation that it’ll, and what I’m really doing is hoping that my car starts, and lo and behold it does. Yeah. Most times. But you see what I mean? Like, we’re doing it all the time. Yeah. It’s just a matter of, well, we’re, when we find ourselves unable to escape our pain, which is when, then the question becomes how does, how do we form durable hope? And that’s really the question, how do we form durable hope? And I would suggest that it is in the face of suffering, that it is the durable hope is most durably formed.

Curt (8m 48s):

And we do it And that Yeah. Yeah. Not that’s,

Amy Julia (8m 53s):

Sorry, it was just that, that connection between suffering and hope, because that’s really what this book is all about. And I’ll, I’ll quote you to you and then ask you to just talk about it a little bit. This is something you wrote, we will become increasingly hopeful, not as a function of simply attempting to be hopeful, rather it will develop indirectly as a byproduct of the persevering work we do in response to suffering. So there is a sense of like suffering catalyzing hope That’s right. In that definition. Right. That, and so could you just, and I know this is the whole book, so we’re getting a little bit of a synopsis of it, but how is it that HopeHope can be, because it’s not the only byproduct of suffering.

Amy Julia (9m 35s):

It’s not the inevitable one, but it is a possible one. And and why, how is that even possible?

Curt (9m 40s):

Yeah. Well, I think as one of the reasons why we explored the particular text from St. Paul’s letter to the church at Rome, the reason we explored this text is because there is an on-ramp to hope. There’s an on-ramp to suffering, actually, even. And so there are some, you know, we have to actually examine what my assumptions are that I’m living with. I’m, we’re all living with a bunch of assumptions about the way the world is and the way the world should be. Yeah. And some of those assumptions that are significant include that I should be able to be master of my universe. I should be able to take care of my own problems.

Curt (10m 20s):

I should be able to, you know, and all the things about the individualistic silos that we have been yeah. Formed to believe that we are, when in fact, that’s not what neuroscience would tell us. That’s not what the material world would tell us. And so we’re actually living lives that fight against the way we’re actually like, made to live. So we’ve got our own set of anxieties already ready to go with this. And so we don’t recognize that in order for me to be hopeful, I form it most deeply in the context of a deeply connected, vulnerable community. That’s how newborns and infants and toddlers form it. They don’t know that that’s what they’re doing, but that’s exactly what they’re doing.

Curt (11m 2s):

They’re forming HopeHope. Yeah. And they’re form most durable hope in the middle of the hardest places in their lives, even as little ones. That’s what they’re doing. And then when we get to places, whether it’s either, you know, chronic medical and physical infirmities, or whether it’s emotional infirmities, whatever, whatever the, the pain is to which we’re responding over time, which is what we call suffering, the real question is, with whom will I dwell as I encounter this pain such that I have the opportunity to practice over and over and over again, sensing others’ presence with me, being present with me, with loving kindness in the middle of my pain, such that my experience of my pain is being transformed because of the attunement that I’m allowing myself to be receptive to from others who are here in this space to love me.

Curt (11m 58s):

And, you know, hope, as we say, is a function. The, you know, the, the mind. We like to say that we anticipate our future based on what we remember. I remember my future. Right. I don’t ever, I don’t ever anticipate a future that is not based on some kind of past experience I’ve had, good, bad, or otherwise hope being a future state. I’m hopeful for something either five minutes from now or years from now or whatever, is always going to be based on what I’m encoding that I’m experiencing in the present moment. And so, if I’m in a present moment in which I am in distress, in pain, and you are being present for me and with me, even if you can’t solve my problem, your presence becomes something that literally begins to, in the best possible way and entangle itself with my pain such that my pain, my, the, the quality of and the nature of how I experience my pain is transformed because of your presence.

Curt (12m 59s):

And if I practice this over and over and over again, what I begin to do is to anticipate a future in which when my pain comes, so will Amy Julia when my pain comes, so will my, so will my community. So will the people who love me, when my pain comes, I’ll begin to anticipate that I’m to be loved. Not that I’ll be left alone in isolation with my distress. Right. But yeah.

Amy Julia (13m 23s):

Well, that’s, I was, so, I wanted get to community because that’s, that’s so crucial, not just to the book and the, and well, I’ll, I’ll say more about community in a minute, but before we get there, back to your point about the individualistic silos, right? We, we don’t live in a culture that put, there are two things I think that push us away from what you are talking about in this book. And the first is the sur being surprised by suffering. That sense of life shouldn’t be this way, which does seem new, right. In human history. Like the idea that we are not supposed to, I, and I don’t mean that people 200 years ago were like, I’m supposed to suffer because I’m bad.

Amy Julia (14m 4s):

It was just an inevitable aspect of life. And so what I’m supposed to do is learn how to do that and learn how to do that well. And so, so there’s that individualistic sense of, or that I guess there’s an individualistic sense of, I’m supposed to figure this out by myself, and second of all, I’m supposed to figure it out and it’s not supposed to be happening. So I’m curious if you could talk about like, the things that we do under that illusion that we’re not supposed to be suffering. Right. ’cause I think we need to admit the suffering before we can even get to the hope. And so if we’re denying suffering, if we’re feeling shame because of Suffering, if like, we get, so I’m wondering if you can just talk about that and then we can talk about if we are able to acknowledge that suffering, what can happen?

Amy Julia (14m 47s):

That’s good.

Curt (14m 48s):

Yeah. Yeah. Well, I, I think a couple things. I don’t think there’s much or anything in the culture. I mean, because evil is very smart. You know, evil doesn’t come to your door at three o’clock in the afternoon and say, Amy, Julia, let’s go rob a bank. Right? Doesn’t do that. It, it’s very, it’s very subtle. And so we don’t have the culture saying, with a bullhorn, nobody should have to suffer. It’s not doing that. It does other things. It, it’s like at and t it says UBU right at UBU, which means you can be anything that you wanna be and nothing should get in your way. And if something gets in your way, then there’s something wrong with the way if you’re in distress, because something’s like there’s a problem.

Curt (15m 28s):

Right? Or we have the little supercomputers that we walk around with in our pockets that make it accessible for us to distract ourselves. Anytime the least bit of distress emerges. I’ll just keep scrolling. Now, this is great for Facebook and for Instagram and for Google and meta. And so this is not great for the human soul. This is not great for human beings. Yeah. And so we’re doing things all the time that are subtly and implicitly training us to believe that we should not have to suffer. Hmm. Right. And, and, and there has been a somewhat exponential advance, especially with the development of the internet in which this has just become the case.

Curt (16m 12s):

But we’ve been 500 years of this in the making modernity. Right. And the, and progress and so forth and so on. When we think about progress, we think about the elimination of pain. So we, in the West, we have a metaphysic in which we wanna eliminate it in the East, we wanna like act as if it doesn’t exist, we’re gonna look, it’s, it, it, it’s here, but we’re gonna do whatever we need to do to like live in the world that’s not material and so forth and so on. Right. And, and this is where I say that the, that the Christian story is the only story on the planet that actually honors shame. I, I mean, I’m sorry, honors Suffering, it’s the only story that honors suffering. Mm. That says about Suffering, that suffering is the expected response, not just of, you know, of human beings, but the entire world to what we humans have done to the world and to ourselves.

Curt (17m 4s):

And, but we’re, but we’re not shaming ourselves because we suffer. And so you’re right, we have all these ways in which we are subtly being trained to avoid it, to pretend it doesn’t exist, So, that when it does show up, we think there’s something wrong with us. We think that there’s a problem in the world. And so naming our suffering is one of the most important crucial elements of it in order for us to be able to take action in response to it.

Amy Julia (17m 31s):

Yeah. I’m reminded, and I’m sure you’ve written about this somewhere, but of that there’s a verse in the Bible where it talks about Jesus enduring the cross and scorning its shame. So even though he endured the suffering of it, he did not actually receive the shame of it in the, you know, and I think, right. That to me was really important in terms of divorcing suffering from shame and recognizing the, that they don’t have to be the same. That’s right. And I think that I, it’s interesting. I mean, my experience of suffering has all been, well, not all, but my most profound experiences of Suffering have been in relation to people I love who are suffering.

Amy Julia (18m 16s):

So whether that is, you know, my best friend’s younger brother died in a car accident. My husband’s mom died of liver cancer and we were her primary caregivers. So we were right there in the thick of it. And then when our daughter was born with Down syndrome, that felt like suffering for a while. It did not continue to feel like Suffering. And I’m really grateful for that. But through her, we have been certainly in relationship with a lot of families who do have diagnoses, where suffering is a part of it. But for me, that experience, especially when Penny was first born, I do think some of my perceived suffering, which it wasn’t really actually, we had a healthy baby who, you know, has lived a really good life, but had to do with shame and had to do with actually thinking that we were going to be in some way outcast because of having a child with an intellectual disability and naming the truth of the situation in our case, which was, in our case, there was not Suffering or shame that needed to be what we were living into.

Amy Julia (19m 21s):

In other cases, I think it’s more that separation of this does not need to be shameful, it’s just about suffering. But I think that’s really, it’s helpful to talk about what does it mean to like name suffering and the power that comes in that, in being honest. And then I guess the, the other thing, and listeners to this podcast will have heard me say this before, but I did, I, my most recent book is about healing. And in it, I came to a place of thinking, you know, honesty, humility, and hope are the movements of healing. That when we, we can’t heal if we’re not honest about our pain, about our woundedness.

Amy Julia (20m 2s):

And if we’re not humble in the sense of asking for help, like if we try to do it alone, even if we know we’re there, but we’re trying to deal with it without telling anyone or talking about it. And if we don’t have any hope that there actually is healing that’s possible, that we tend to get stuck. So I wonder if we could maybe move from that honesty piece to the humility piece is what I call it, but, which is that community aspect, because Yeah, what I love about your book is that you’re really not saying pray, and you are going to be able to move from suffering to hope. Right. And not to say prayer couldn’t be a part of that, but there’s so much emphasis on like other people in the flesh.

Amy Julia (20m 44s):

Could you just like speak to why that is so crucially important?

Curt (20m 48s):

Yeah. Well, you know, as I as our, our, our friends at the Bible Project, like to say everything you need to know about human beings, you could learn by reading the first six chapters of Genesis. You don’t really need to. So true. You don’t have to read anything, anything past that. Like, everything you need to know. It’s, it’s right there. And one of the first things that we see on the second page of the Bible, which is what, as I hear you, which is really what you’re really coming back to, this is a recapitulation like God, God doesn’t appear to be changing his methodology or his intention for the creation, just because we’re pretty broken. He’s still going back to his, those first two pages of the Bible and say like, folks, this is how we’re gonna do it. And so even when we’re broken and it comes to then our, our longing for a need for healing, your notion of humility as the Jews would say that to be a person of humility is to know who we are and to know who we are not, and who we are are vulnerable creatures.

Curt (21m 43s):

That that’s who we are. The man and his wife were naked and unashamed, right? They were naked in this, in, in, in Genesis two. This notion the Hebrew would, are emphasizing nakedness not just as a physical reality, but as this, this state of vulnerability that to be naked means I actually need your help. I like, I need you in order for me to be okay. I, I don’t need you. Like, I don’t it, it’s not because I’m broken. Do I need your help? Like, I’ve needed your help from the beginning when things were great, I need your help. And I, I need your help and I need your protection. And vice versa. This is what we need in order for us to flourish. This is required. And of course, part of what shame does is it locks me into this place where I worry about needing you.

Curt (22m 28s):

Because at some point you’re gonna say or do something that’s gonna humiliate me, that’s gonna shame where you’re gonna, you know, something’s gonna happen and you’re gonna leave. So it’s hard to trust. So how am I gonna be able to be vulnerable? But this is the point, our naming things actually to, to name that I need help is a, is a powerful way of saying, oh, I’m actually going to live the way I was made to live from the beginning in the, in the best possible world. That’s now in our world, that can feel scary. But once we start to practice that we begin to recognize, and this is, you know, coming back to Hope HEAL’s camp.

Curt (23m 9s):

You know, people show up and they’re like all these people who’s like, oh my gosh, like, we’re so different and you’re just like me. Like I, I feel like I’m being seen literally in the flesh for the first time in a way that I’m never seen in the world that I typically occupy in, you know, where, where I live. And so this is not, so, you’re right, hope is not a thing I conjure in my own head. Hope is a thing that I form by literally being in the room with other human beings, by whom I’m being deeply seen, as we say, seen sooth safe, secure in an embodied way. Not in some just abstract way about abstract notion of ideas, but an embodied way in which I feel the comfort of your gaze, of the tone, of your voice, of the embrace of and embrace all the things even in the face of me just having said to you things about myself that I hate.

Curt (24m 5s):

Or even after I just told you my story, what happened to me or what happened to my child. And as we have these experiences of being loved, my experience of my suffering of my pain is transformed because I have a story that I have told about my pain. And as we say, as we talk about in the book, you know, we suffer for these, these three reasons, things that happen to us, things that we do to ourselves, and we suffer because we are running to the light. We suffer when we are gonna work toward growth and integration, so forth. But it’s that second category, the things that we do to ourselves that, you know, by volume is the most common way that we suffer without our knowing it.

Curt (24m 51s):

And so I have these stories that I tell myself that I subject myself to. And it’s not until someone else walks in the room and starts asking me a set of questions out of curiosity, and not with condemnation, not with shame, that I can begin to imagine a different story that I can’t tell if you don’t help me imagine it ahead of time. Because I’m so stuck in my imaginative processes of brokenness. We like to, as we know at the Hope Hills Camp, you know, Jay and Catherine like to talk about, you know, everybody has a disability. Some are more obvious than others. Yeah. And, you know, we, we, we can say, gosh, it’s pretty plain that one of our disabilities is that we’re not very good at loving one another.

Curt (25m 32s):

That’s pretty plain, but like, just look at our world. But there is a disability that’s actually greater than that. And this is what evil counts on And. that is my inability, my disability in being able to be receptive to being loved.

Amy Julia (25m 47s):

Yeah.

Curt (25m 49s):

And it is in these embodied spaces that I let myself take the risk of doing that

Amy Julia (25m 60s):

My mind is going in multiple directions and I’m trying to decide what, which one I’m gonna say next. I’m just thinking about our daughter Penny and the ways in which, although she has much more visible disabilities, both in terms of some physical, you know, fine motor skills and certainly some intellectual disabilities. she is, I think I can say, without being sentimental about it, more able to love and be loved than most of the other people in my life. And I’m thinking about this moment I had at Hope Hill’s Camp, where one of the adults who was there said, pulled me aside and said, oh my gosh, I’m so sorry.

Amy Julia (26m 45s):

I feel like I am just like monopolizing Penny’s time. I keep seeking her out because I just want to be with her. She makes me feel so loved. And I essentially started crying because I said, no one has ever said what you have said to me before. She truly was apologizing to me for the time she spent with Penny. ’cause she saw it as like, I’m just like taking the love that this young girl, young adult wants to give me. And I was like, please keep going. I mean, this is, She’s very happy And this is great. That’s, but that’s awesome.

Amy Julia (27m 26s):

I just am so struck by that, that sense of when we are in a place where we’re able to be vulnerable and where we start to see that naming our suffering, that living in that place like that, all those things are actually happening and real, then we are more able to receive it too. Like there’s a mutuality to the giving and receiving that can begin to happen Right. When we put our, our armor down. And that’s, I’d love, well, you just described, ’cause you do this so beautifully in the book, we’ve got there a lot of different kind of case studies almost, although that makes it sound more clinical. There’s stories you tell of men and women who are parts of confessional communities.

Amy Julia (28m 6s):

Could you describe a confessional community? Because most people are listening to this and they’re like, well, I’m never going to hope heal camp. But like,

Curt (28m 14s):

What,

Amy Julia (28m 14s):

You know, what is a confessional community and how could people even find one or access that? Yeah.

Curt (28m 20s):

Well, first thing I would say is by all means, if you think you’re not going to hope Hill’s Camp, you can always volunteer. You can always do that So. that, that’s one thing to consider. I, I would say first and foremost that as we like to say, the brain can do a lot of hard things for a really long time. As it, as long as it doesn’t have to do it by itself. Hmm. We are, you know, we, this is common kind of communal lingo now. We, we were made for connection. We’re, we’re like, we live, we, we, we were made. And yet we actually do live kind of against that grain. We tend to do things that keep us separate from one another.

Curt (29m 3s):

So we really do believe, you know, and this, this came outta the work in our practice, but it’s now being extended in other domains. This, it’s confessional community is number one. It is by any other name group psychotherapy. So it works with the dynamics of group, inter, inter, you know, group psychotherapy dynamics. But it, it also explicitly sits within an understanding of what it means to be human from a Christian perspective. So it means that we believe that we are created, that we’re not making ourselves. It means that we were created to be loved and to love. It means that we were created to create things, create beauty and goodness in the world.

Curt (29m 44s):

It also means that we, we acknowledge that we are broken. And my tendency is not to love and be loved and to create beauty and goodness in the world without my messing it up. I need help in this regard. And it also accesses the principles of this field that I work in called interpersonal neurobiology. So it’s this, how does brain science, brain and relational science attachment and so forth, how do these things work together to shape one another? What are lots of different ways that we insert and include language and practices that have to do with that way of kind of implementing neuroscience into the present moment that’s happening.

Curt (30m 24s):

And you know, one of the things that we, that we say Amy Julia in these, in these spaces, when people think about, you know, psychotherapy, let alone group psychotherapy, you know, people have ideas about what that means and what happens, you know, in the office behind the door, like all these like strange things, right? And to which I say, look, everything that happens in these confessional communities is actually happening outside these walls in your church pews, at Safeway, in your bedroom, in your boardroom, in your kitchen, on the playground. It’s all happening. Every, what separates what we do in this space is that we are explicit about what actually is happening.

Curt (31m 6s):

We’re actually naming the things that are taking place in the room. And we’re not taking, we’re not just naming them as abstractions, we’re naming them in terms of like, we, we don’t just, people don’t just come into these groups simply eventually to talk just about the things that are happening outside the room. I’m gonna talk about ’em in marriage or my parents or my child or my work or my this or my that. All those things are like portals. Those are like doorways into what happens when the community starts to talk with themselves about themselves, about what’s happening in the room between each other. And of course, this is what’s, you know, we are, we are having things that are happening between us and other people all the time that we don’t name because there’s way too much fear and shame in the room.

Curt (31m 52s):

It happens between us, you know, at the checkout counter at our hotel when we leave because our room wasn’t okay. It happens in, again, in all these other places. And I think one of the things that, you know, this book was really kind, kind of emerged as an acknowledgement of all the Suffering that people bring into this space. It is a kind of distilled space where Suffering comes. But what makes it a space of Healing is that people are practicing naming their suffering and they’re naming what, like how does that show up in real time and space? And how is it showing up right now? How many times in these groups, for instance, will a person say like, well no, I don’t, I don’t wanna talk about that anymore because you guys have already heard that part of my story.

Curt (32m 38s):

Like, like 10 times. Like, oh. And so it’s not okay for us to hear at the 11th. I mean, this is part of how it is that we ma many of us, like we have all kinds of stories that are about our Suffering that we assume nobody wants to hear. Nobody’s gonna want to hear this because this is too much, this is too big, so forth and so on. And so I simply pile on my suffering by not naming it. Hmm. But it is in these confessional communities where we’re not just talking to each other, but we’re also inviting into this space what we hear and learn and pray about in the texts that we’re hearing from outside. Because my suffering is not a thing, as you rightly said earlier, I can’t just hope on my own.

Curt (33m 23s):

I’m going to have to borrow your hope for me. Yeah. Until mine can catch up. And that’s the way that I form it. As we like to say, at the end of the day, I don’t form HopeHope for me, we form hope HopeAmy. And that’s the only way hope is ever formed. Because that’s how the human brain only ever grows and thrives and flourishes in a context of this rhythm between I and we and I and we back and forth and back and forth as we were made to do from the beginning.

Amy Julia (33m 57s):

Hmm. I love that idea of forming hope for each other. And I think, again, one of the really important pieces of this book for me was that sense of this is not simply about going to therapy or knowing God, both of which are great aspects of a Healing process, but without other people who will persevere with you in the midst of suffering. You won’t really know actually what it means for God to love you because there is just this embodied reality that we are meant to give one another that reflects I that idea of like glorifying God and you have a chapter on glory as well, but the, that what we glorify God when we reflect back to God, who God is, right.

Amy Julia (34m 50s):

That that is actually what we’re able to do in loving each other and in loving each other in that patient way of sitting in the suffering together and saying, I’m not gonna leave. I had a, a woman write to me this week and say, you know, I have in people in my family who have a child with, you know, terminal diagnosis and what what do I do? You know, and I wrote her back and talked about your book and I said, you know, you just stay and sure. Bring the meal. Absolutely. If they need an errand, like that’s a part of staying, but like more than anything else, you stay.

Amy Julia (35m 32s):

And she said, you’re right, I wanna fix it. And that’s not the answer. The answer is just to be there and bear witness with them to the pain of this. Because I, and I think that’s this other important thing, especially in Christian circles, although there’s probably a kind of secular version of it too, with the idea of toxic positivity that like HopeHope is not toxic positivity in which we just say everything’s gonna work out fine, or everything happens for a reason. Like there’s a depth to it that actually can still hold the reality of pain and loss. Yeah.

Curt (36m 5s):

Right.

Amy Julia (36m 6s):

And yet still hold onto hope. And I do think that somehow the, the being with one another is a part of that.

Curt (36m 14s):

Yeah. I mean, I think it, it’s true that it, it’s like a lot of things Amy Julia as humans that, that happen to us in that I don’t become a really good piano player by becoming a good piano player. I become a good piano player. Becoming a good piano player is a byproduct of hours and hours and hours and hours of practice. Right. I don’t form hope because I set out to form hope. I form hope as a byproduct of persevering, practicing allowing myself to be loved in the middle of my suffering.

Curt (36m 55s):

And that perseverance which leads to character, which is a word that’s also crucially important. Character, implying the durable qualities and characteristics of how I am in the world, how I comport myself in the world. Am I a person of patience, my person of kindness, or am I person irritability? Am I person who’s short-tempered? Those are things that are durable and as we say, hope becomes this extended way that I imagine the future based on the things that I’m practicing right here and now, over and over and over and over again. And the beautiful thing is that because I imagine a future that is hopeful, that imagined future circles back around into my present moment and continues to support my willingness to continue to be present then for others.

Curt (37m 53s):

I think this is also part of it. It’s, you know, one of the things that that’s also true about these confessional communities, that is, that is different if, if you, if you’re going to see a counselor, for example, in for, so a for our audience, many of our in our audience might have gone to see an in a counselor who sees them for their individual particular issues that they’re gonna see them for. And that’s helpful. And it’s, it’s, it’s a, it’s a, it’s a lovely thing that we have this in our day and age, these, this opportunity for Healing to do this. But there is something that does not happen in an individual counseling setting that does happen in a confessional community setting, And. that is that if you’re my therapist and I’m telling you my story and this being extraordinarily helpful for me as you help me do this, you would find along the way that the work that we do together is also going to speak to your own story.

Curt (38m 46s):

It’s gonna speak to things in your own life and it’s gonna be helpful for you as we like to say. And any, any therapist worth their assault will say, my greatest teachers are my patients. Right. And this is how I ima things about my own story come up and I work on this. But what you’re probably not going to do very often is that you’re not going to tell me every now and then, well, Curt, let me just, lemme I just wanna share some things from my own story about, about how your story is transforming me. But in a confessional community, one of the things that every member gets to experience is how they’re being vulnerable actually becomes transformational for other people in the room.

Curt (39m 26s):

And a significant part of our healing that we often weigh underestimate, which doesn’t really, we don’t really, we’re not really able to access in individual psychotherapy settings, is the way I give myself away to others in vulnerability. Not, I, I I’ll tell patients who, who I’m wanting to join these, I say, look, I, I don’t just think that this group is gonna be helpful for you. I think you are gonna be helpful for the group, but not because of your witt and your wisdom, not because of the way that you solve people’s problems. You are gonna be helpful counterintuitively by virtue of being vulnerable with the parts of you that you hate the most. Right. Of course. People find this really quite distressing at first And that they, they, they’re not really sure this is a very good idea.

Curt (40m 14s):

And it is, it, it, it it is, it is consistently striking to watch the way others ex people experience Healing when they hear the way that their own suffering and their own sorrow and their own vulnerability and their brokenness and their revealing of that creates opportunity for others to come into the room and say, oh my gosh, I don’t think I ever would’ve been able to name what I’m about to name. If you hadn’t said what you just said, thank you. So, and you’re like, I I, and, and we would say like, this is, this is good Friday writ large.

Curt (40m 55s):

Right. Because this is, we are healed by his stripes. We are healed. We are healed counterintuitively not because God comes and magically changes all of our stuff. It’s because God comes and suffers with us and dies with us. And we point to that and say, that’s me. but we also point to that and say, I’m him and I’m not alone with this and with resurrection, we then say, oh, and I’m, he’s, he didn’t just come to be with me. He came to be with me fully So that I can fully go with him where he wants to take me.

Curt (41m 36s):

Yeah. But I can’t, I I I, it’ll be, I’ll be hard pressed to let to, for all of me to go if there are still parts that are suffering that I don’t wanna name.

Amy Julia (41m 46s):

Right.

Curt (41m 47s):

Yeah.

Amy Julia (41m 51s):

And I think that sense of one of the huge barriers being our inability to be loved again in the broken place, it’s kind of one thing I loved your saying, why, why wouldn’t we listen 11 times? If you need to say it 11 times, we’ll listen 11 times. Like that’s, that’s why we’re here. But I I, that is where again, like that word shame comes up the thought of like, I, and I, I’ve, this is another thing I’ve thought about with healing because so often I feel like whether it’s me personally, but also especially in relationships where I’m like, how are my husband and I back in the same place? Like, how are we having the same argument?

Amy Julia (42m 33s):

We are not getting anywhere. I can’t believe this. And I finally,

Curt (42m 37s):

Have you been, have you been in my kitchen? Well,

Amy Julia (42m 40s):

You did say 37 years, so I only imagine

Curt (42m 43s):

Yes.

Amy Julia (42m 44s):

But, but what I’ve started to believe is that we are spiraling upwards. And so yes, we’re going back to the same territory, but it’s actually not exactly the same. That’s right. It’s not a straight line. There’s nothing linear about it. That’s right. And yet, even the fact that I’m noticing we’re here again, you know, what happened last time? Is there anything that we can do to repair more quickly or to acknowledge hurt or whatever it is And that has really helped me in my own coming back to the same thing. And I can imagine the 11th time telling the story is not the same as the 10th or as the first, even though it feels like the same story, it’s actually not the same because there’s been some Healing that has been happening along the way.

Amy Julia (43m 28s):

It’s just not done yet. Right. And so you gotta tell the story again. And that’s a part of, but I love that idea that the persevering is being, is allowing, it’s persevering in allowing myself to be loved. Not persevering in the sense of like, like gritting my teeth and bearing the pain for a longer period of time. Those, that’s what I think I’ve thought of as like persevering through suffering is like simply continuing to bear pain as opposed to in the midst of this vulnerable, humble, sometimes what feels like a humiliating place, I’m going to continue to allow myself to be loved and not think I have to fix it and not think I have to defend it or pretend that I’m better than I am.

Amy Julia (44m 13s):

Right. Better by which I mean like feeling better than I am, but I’m just going to allow myself to be loved here. I think that’s really beautiful and yeah. Makes sense that that would actually lead to

Curt (44m 24s):

HopeHope. Yeah. We interestingly enough, we, this is where neuroscience can actually be helpful in shifting people’s imaginations. So you want to be a better pianist. And so you are practicing and you think I’m just practicing the same scales over and over. It’s the same scale. And until we say, well, actually as far as your brain is concerned, even though the keys on the piano that you’re playing are the same keys as far as your brain is concerned, it’s not at all the same scale as it was last week or as it was a month ago, or as it was six months ago or 10 years ago. And you’ll find virtuoso penis that are doing the same workout scales after 15 years of professional work that they were doing when they first started to play.

Curt (45m 17s):

But every time they do, as far as their brain is concerned, it is a different scale because they are strengthening the neural networks in their mind are being changed, they’re being transformed. And so even though outside my skin, it looks like I’m doing the same thing inside, I am not doing the same thing at all. Which is why we say to people, when you are truly being seen through safe, secure, when you’re, when when your story is being truly received, you never tell your story story. You never tell the same story twice. You never do.

Amy Julia (45m 52s):

Yeah. Yeah. That, I mean, that’s really helpful to me. And there’s so much more we could say, but I want to make sure that before we go, the the last thing I wanted to ask was for people who are listening to this podcast and maybe they’re kind of feeling a little bit of that vulnerability and like, oh gosh, I’m right at the beginning of this. There is suffering that I haven’t named. There is shame that I’ve tried to cover up. Like I’m, I’m right at the beginning and I, you know, don’t have a confessional community and I maybe I don’t even have a therapist, you know, maybe I don’t even have, I like where do you start in terms of practicing, right?

Amy Julia (46m 32s):

I mean, like what is that first scale? How do people begin that process of moving towards HopeHope?

Curt (46m 42s):

Well, it’s a great question. And Amy, Julia, I think it’s one of the more, it’s probably one of the most common questions that I’m asked, like, where can I find this? Where can I go, where, where can I and right. And where can I get a confessional community? Where can I get whatever, which is completely reasonable to which my response is often, it is not a thing that you find, it is a thing that you work to create. And it is a risky proposition. And I would say make a list of three people that you can think of that you would like to begin to tell your story to And that you would like to hear from them, their story. Now of course when people do this, they’re like, well, yeah, but no, these, these people won’t do this.

Curt (47m 26s):

Like, well, we’re not gonna know until we try. Right? And it’s possible that we would say, we tried and they thought I was crazy and this person I tried and they didn’t have time and this and so forth. And then I would say, then gimme three more names and when those are done, then gimme three more names. Because I can tell you the world is waiting for you to find them. The people that you’re talking to that say they don’t have time or they think you’re crazy, are people who are afraid to tell their stories.

Amy Julia (48m 3s):

Yeah.

Curt (48m 4s):

And it simply means you haven’t found the right person or persons yet to begin to do this.

Amy Julia (48m 9s):

Yep.

Curt (48m 12s):

We, Christians would say that in the first place. God knows all about this. As Paul Borgman says in his beautiful book, Genesis, the Story we haven’t Heard, he makes the observation, who knows how many people God asks to go with him, to Canaan before he finally found someone in Abraham who said yes. Right. Because we don’t have any stories about it. We do know that Jesus asked all kinds of people who said no. So we know that God knows that this is not easy to get people to cooperate with him. Like he’s he, like he wants to, he partners with like, yeah, after the second page of the Bible, there’s nothing that God does in the Bible that does not include or require the participation of human beings.

Curt (48m 53s):

And so if we’re gonna do this, we have to do this with other people. Yes. People are afraid. And I want to encourage us to know that yes, it might feel, there’s no question, it’ll feel hard, it’s no question. But our choices to remain in our shame and our suffering, that’s our choice. We like to say, look, you can work hard and stay in prison, or you can work hard and go free. Hard work is not an option. If we’re gonna work hard in the effort of doing, of, of, of forming durable hope, I can tell you that it, will it be risk-free.

Curt (49m 33s):

No. But it will be the most glorious work that you ever do in your life.

Amy Julia (49m 39s):

Hmm. Well I love that. That’s a really beautiful place to end this conversation because it is something that all of us can do. So thank you so much for all of these words. And I do just really, I’m really grateful for your books and the very, your podcast and the various ways in which you speak and serve other people. I mean, just tirelessly. So thank you, thank you, thank you. And thank you for sharing with us today.

Curt (50m 8s):

Oh my gosh. Amy Julia, my pleasure. I-I-I-I-I don’t deserve my life and this will be yet one more reason for why That’s true. So thank you.

Amy Julia (50m 22s):

Thanks as always for listening to this episode of Love is Stronger Than Fear. You will definitely wanna check out the show notes So that you can find Curt’s latest book, The Deepest Place And, that will offer an even deeper dive into what we were talking about today. I also wanna let you know that Sissy Goff will be here with me next time. We are talking about her book Worry-Free Parenting, and I’m sure you’ll wanna hear that too. It’s, yeah, it’s been quite something to read and think about that book. Also, if you go over to Amy Julia Becker dot com slash newsletter, you can join my email list, And, that email list does include reminders about these podcast episodes.

Amy Julia (51m 2s):

I would love for you to catch everyone. I will also note that on the day this episode drops, it is Halloween and also the final day of down Syndrome Awareness month. So if you are looking for more content related to down Syndrome awareness, the past two episodes of this podcast were related to down Syndrome and topics related. There you can also find even more writing information, some essays I’ve written, some things that our daughter Penny has written about her own life, or on my social media pages or on my website, Amy Julia Becker dot com. I also love to hear from you. My email is Amy Julia Becker [email protected]. So please be in touch and I’d like to say thank you.

Amy Julia (51m 45s):

Thank you to Jake Hanson for editing the Podcast to Amber Beery, my social media coordinator, because she makes everything happen and I really, I mean really and truly would not be here without her. And finally, as you go into your day today, I’m thankful for you that you’re here, that you’re listening, and I hope that you’ll carry with you the peace that comes from believing that love is Stronger Than, Fear.

Learn more with Amy Julia:

- S6 E4 | The Beauty of Life Together with Willie James Jennings

- To Be Made Well: An Invitation to Wholeness, Healing, and Hope

- S6 E20 | Strong Like Water with Aundi Kolber

If you haven’t already, you can subscribe to receive regular updates and news. You can also follow me on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Pinterest, YouTube, and Goodreads, and you can subscribe to my Love Is Stronger Than Fear podcast on your favorite podcast platforms.