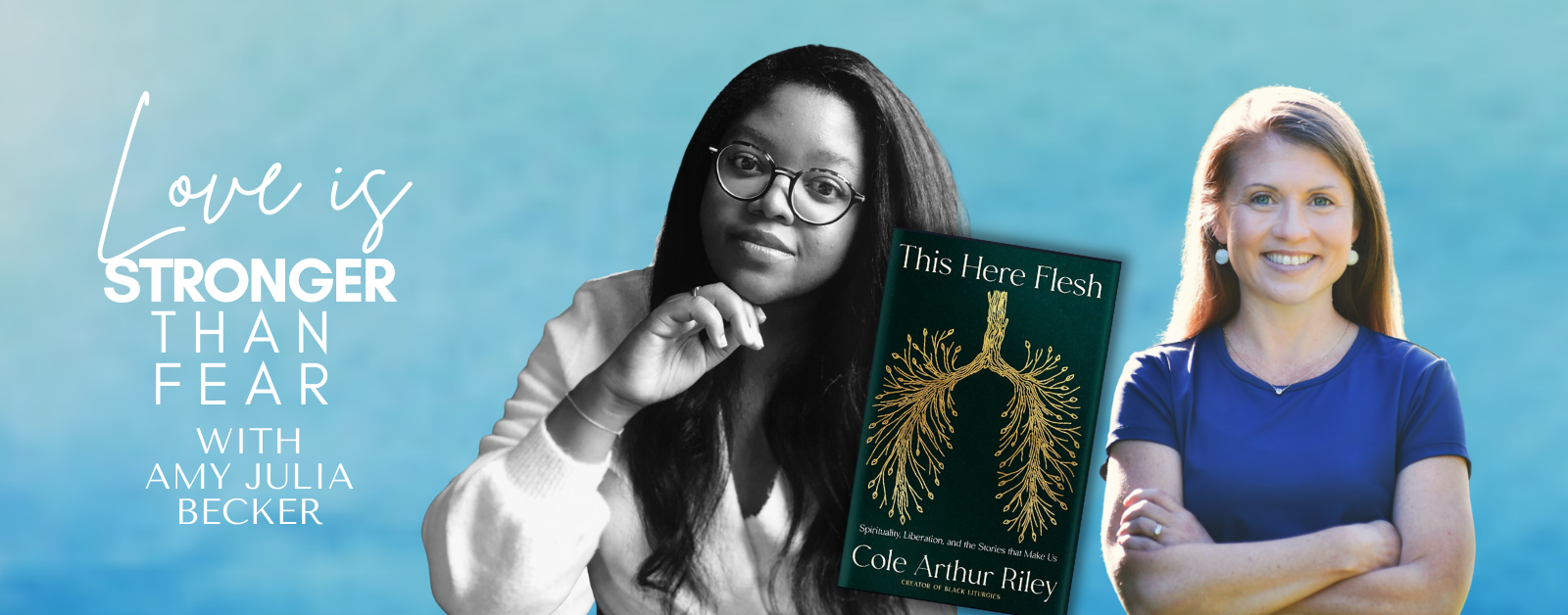

The effects of trauma often surface in our embodied existence. What about hope? Cole Arthur Riley, author of This Here Flesh and creator of Black Liturgies, talks with Amy Julia Becker about bearing witness to the pain of the world through our bodies, the healing found in belonging, and the importance of weaving together self-care and community-care for social healing.

Guest Bio:

“Cole Arthur Riley is a writer, liturgist, and speaker seeking a deeply contemplative life marked by embodiment and emotion. She is the founder and writer of Black Liturgies, a project seeking to integrate concepts of dignity, lament, rage, justice, rest, and liberation with the practice of written prayer.”

Connect Online:

- Website: colearthurriley.com

- Instagram: @blackliturgies

- Facebook: @blackliturgist

- Twitter: @blackliturgist

On the Podcast:

- Cole’s Book: THIS HERE FLESH: Spirituality, Liberation, & the Stories that Make Us

- Black Liturgies on Instagram

- Beloved by Toni Morrison

- The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois

Interview Quotes

We can learn from the disabled and chronically ill community because they’ve had to learn what it means to survive a culture that really succeeds by us being disconnected from our bodies. We’re a lot better at being tools for capitalism, for production…if [we’re] disconnected from the pain, from the aches, from the joints, from [our] needs.

Trauma can certainly be passed down—the effects of trauma—but I also think a lot of beauty can be passed down… hope and habits of hope.

Finding a community of belonging that…will not reject me…even if I come to different conclusions than them….a community that gives you the freedom to explore and question and resist I think is the path to young people in this time, it’s the path to young people who feel so skeptical and so trapped and smothered.

When my belonging depended on believing in a white God, depended on believing in a God who was indifferent to Black suffering or who didn’t center Black suffering or all of these things, my faith and my experience of God was so small…I was more so experiencing this desire to belong, to fit into these spaces that ultimately didn’t love me or care for me.

Find people you feel safe to ask questions with.

We’re trying to find this one-size-fits-all path to healing for so many people…It’s just not true.

I hope that we as humans can learn to be more acquainted with the not-yet and the waiting and that fact that we’re healing as we’re constantly being wounded and we’re healing as we’re constantly remembering old wounds that we have forgotten about.

Whenever I am giving myself the freedom to experience pain, to name aches, to name my anger, I also can point it in the direction of hope and to use my lament to claim, “I want more for myself.”

Lament is not about the world being bad…it’s about believing that the world is worthy of goodness, that my neighbor is worthy of goodness. That’s where the sadness comes from, and if we shift that, I think those emotions can be experienced as a form of hope.

We have to be inclusive of language of community-care as well. Self-care is just never going to be sufficient. Self-awareness is never going to be sufficient. I think we were made for a lot more than that. We were made for this kind of communal care, communal attunement.

Out of the community-care, out of the care of the individual for the individual, we can expand into social healing. We can expand into policies, into infrastructure. The self-care and the collective-care—community-care—that’s where things begin. They’re the groundworks for social imagination in general.

Season 5 of the Love Is Stronger Than Fear podcast connects to themes in my newest book, To Be Made Well, releasing Spring 2022…you can pre-order here! Learn more about my writing and speaking at amyjuliabecker.com.

*A transcript of this episode will be available within one business day, as well as a video with closed captions on my YouTube Channel.

This post contains affiliate links.

Note: This transcript is autogenerated using speech recognition software and does contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Cole (5s):

Lament, it’s not about the world being bad. You know, I think that’s the people say it’s like, you’re just saying the world is all bad. It’s no, it’s about, it’s about believing that the world is worthy of goodness that my neighbor it’s worthy of goodness. That’s where the sadness comes from. And if we shift that, I think those emotions can be experienced as a form of hope.

Amy Julia (27s):

Hi friends, I’m Amy, Julia Becker. And this is love is stronger than fear. A podcast about pursuing hope and healing in the midst of personal pain and social division. And before I get to today’s episode, I do want to let you know that my next book to be made well, an invitation to wholeness, healing and hope is about to be released. It comes out on March 15th and for anyone who’s listening to this podcast, I mean, I just said it, it’s a podcast about pursuing hope and healing in the midst of personal pain and social division. That’s what this book is about too. So I think you’d really love it. And I would certainly love for you to head over to my website, Amy, Julia becker.com, where you can read an excerpt.

Amy Julia (1m 7s):

You can pre-order it. If you pre-order it before March 15th, you should have it on your doorstep on March 15th. And you also could let other people know about it because I would love for this book to be a part of the healing work that God wants to do in our broken world. All right, onto today’s episode today, I get to talk with Cole Arthur Riley. Cole is the creator of the black liturgies on Instagram. She is also the author of the newly released book. This here flesh, it’s a beautiful book. We are going to be hosting a giveaway for it. So check out the show notes for details. It’s, it’s really quite something. And I highly recommend it. Cole and I had a chance to talk about what it means to be spiritual creatures who live in bodies about bearing witness to the pain of the world, through our bodies about the role of anger and sadness in hope about faith and mystery and contemplation about the relationship between personal communal and social healing.

Amy Julia (2m 6s):

So there’s a lot of good stuff ahead, and I’m glad you’re here. Well today, you’re in for a treat because I have the privilege of talking with Cole, Arthur Riley, and we’re going to talk about her beautiful new book. This here, flesh. I highly recommend it. I’m just going to say that from the top. I hope everyone will read it honestly more than once and spend some good time with it. But before I explain why I think that I’m just going to say Cole, thank you for being here.

Cole (2m 38s):

Thanks for having me.

Amy Julia (2m 40s):

Well, I really do want to talk all about your new book today, but before we do that, I feel like I need to introduce the listeners who are here to the work that you do on Instagram. Probably some of them are already well aware of it and others are not. But just to introduce you through this lens, you are also the creator of black liturgies. And I thought that rather than having me try to describe what you do in that space, could you just tell us the story of how this account, this black liturgies space on Instagram came to be

Cole (3m 14s):

Sure I began black liturgies in at the end of June of 2020. So, you know, it was during the period where a lot more people were reckoning with the murders of Ahmad Arbery and George Floyd and the resurfacing of the murders of Briana Taylor and Elijah McClain. And I had been in liturgical spaces for a while at that point, maybe five to eight years and have found a lot of comfort in written prayer and contemplative spirituality.

Cole (3m 55s):

But yeah, just at that time, felt like I was in a lot of Christian spaces that weren’t really capable of fielding and understanding my sadness, my anger in a way that was helpful to me and I, so I, I really, when I’m being most honest, I say I started black liturgies out of anger. You know, I float there with some righteous anger in there, but yeah, that’s how it began. And I was truly envisioning kind of like this small intimate little community. I was just laying in bed. I said, I think I’m going to start this thing called black liturgies. Maybe there are some other kind of like-minded black people interested in this kind of thing.

Cole (4m 40s):

And it, it quickly became a lot bigger than that.

Amy Julia (4m 46s):

I mean, yes. And so are so many people including this white person who reads your words almost daily. But what I will say is I was thinking about the, the growth of black liturgies, which is unusual. It seems to me, or surprising to me in a couple of different ways, like one, you are unapologetically embracing blackness and writing, not only from the perspective, obviously of being a black woman, but also with a commitment to a spiritual practice, a commitment to naming truth about our political and historical moment when it comes to race and justice and injustice.

Amy Julia (5m 28s):

And you’re also doing it through words on a image based platform. And it’s a beautiful, like you, you choose your fonts very well, but it’s not, there’s nothing flashy or there are no shiny objects. You know what I mean? Which it seems to me is often what we gravitate to on social media. And so the combination of those things to have, I mean, over a hundred thousand, I think it’s almost 150,000 people who are following this account. I’m sure they’re even more who are blessed by these words every single day. Were you surprised by the growth of this site? And I’m just curious if you kind of, what do you make of that?

Amy Julia (6m 8s):

Why are people responding to your words in this way?

Cole (6m 12s):

Yeah, I mean, absolutely absolutely surprised for the reasons that you’ve said, like when you zoom in with that level of particularity, you know, womanness, blackness, Christian newness, like language and especially, you know, I think in a lot of progressive Christian spaces, there can be resistance to like to written liturgy because there’s, there’s something kind of scary about the organization of it, about believing and some kind of authority in it even. And, you know, like when I first encountered liturgy, I often would kind of be like, you know, I I’ll choose my words.

Cole (6m 57s):

You know, I don’t, I don’t, I don’t want, I don’t want to pray in unison. Like, you know, I want the independence. And I think a lot of that comes from a level of distrust and having, you know, voices, particular voices be suppressed for so long that when you enter a spiritual space and you’re being told what to say, it can be really problematic. So I just, I didn’t have an imagination for so many people being interested in that kind of spirituality where I’m using we language, at least in the prayer portion of the person in this we language. And it’s like, you, hopefully people are reading that with the we in mind. So yeah, I, I didn’t have an imagination for it, but in hindsight, some of it makes sense to me, you know, the, the, the timing where I think a lot of black Christians, a lot of black spiritual people were just kind of feeling burnt out and frankly afraid to be fully themselves and fully in their pain and evangelical Christian spaces because of, you know, police brutality because of the election season and all of that.

Cole (8m 9s):

So I think there was something kind of timely that spoke to a loaning that people had, like maybe I don’t feel safe in church right now, but is there a space for me still to encounter the divine, to encounter God in somewhat of a community? Yeah.

Amy Julia (8m 27s):

Yeah. I mean, again, it’s been amazing to watch the influence and the growth of that space. And I think just to see, it’s interesting, cause you speak about any right about like what comes out of anger, but also that what comes out of sadness. And yet I think there’s a quality of beauty and hopefulness that maybe we’ll get a chance to talk about in all of your writing. That’s true. These written prayers, it’s also very much true in your book and there’s, I guess an honesty as well as a commitment to, there’s just a, there’s a, an attention and a care that you are giving in all of the writing that you do.

Amy Julia (9m 12s):

And I really appreciate that and I’m sure people resonate with it that, you know, even if it, I don’t know sparks questions or, Hmm, I’m not sure I do think that or feel that I think there it’s hard not to be drawn to the sincerity and honesty and vulnerability and power of the words that you’re putting out into the world. So first of all, just thank you for that before we get too much into this year flash, I did want to hear about your own spiritual journey. So you’ve mentioned being in liturgical spaces in recent years, there’s a scene in the book where you write about visiting a Baptist church for a few months as a middle-schooler, and I’m gonna quote you, you say it was your first encounter with a spirituality that demanded your death far more often than it ever advocated for your life.

Amy Julia (10m 3s):

So I was just struck by this picture of a middle schooler who is kind of giggling in the pews with her sister and not quite on board with like the message that’s being proclaimed and not there for that long. And now as a grown woman in a liturgical space, writing prayers for hundreds of thousands of people every day, like how, how did that happen?

Cole (10m 24s):

Yeah, it’s so funny because my sister who is somewhat of a spiritual person, but certainly wouldn’t identify as a Christian. Like we always laugh about kind of my like career trajectory and like you’ve never would have thought I would go from, you know, that small Baptist church where I did not feel cared for. And I felt a lot of confusion. So I’ll speak to that. You know, I was, I was a kid, we were kids and I think people who were born into Christian spaces and like evangelical Christian spaces, but I would say the same is true otherwise, but specifically even Christian spaces, like you can kind of be, at least in speaking with my friends, you can kind of become numb to like the strangeness of it, the strangest of the language and the messages being communicated.

Cole (11m 20s):

And so I wanted to be sure to communicate faith as I first encountered it, which was just terrifying and hilarious and, you know, strange in, you know, I went to this, this black Friday service and we have this pastor sweating and like pounding his chest and, you know, pretending to jam nails in his hands. And it’s like, I’m a kid. And I’m like, what is happening? You know, like when we, when we sing that song, nothing but the blood of Jesus and, you know, think about, you know, an 11 year old encountering that concept for the first time. Like nothing but the blood of this man, like it’s grotesque, it’s, it’s grotesque.

Cole (12m 4s):

It’s strange. And I really think it’s, it’s good and right to put ourselves back into that, that space, because there are people still in that space of like confusion and terror when they encounter Christian spaces. But yes. So I did not go to that church for long and really in high school because of some conversations in an English class began thinking more about truth than what is truth, which led me to think about religion and God. And I started asking these big questions of, you know, like where, where are we from? And, and is there a truth and can I know it, and I’ve always been a skeptic.

Cole (12m 48s):

Anyone in my, my, my family always says, you know, Cole was born a skeptic, you were born, a squeaky, came out a skeptic and it’s true. And so I entered religion with this. Like the skepticism is kind of, you know, a researcher as, as good of a researcher as a 17 year old can be. And I think I just needed to encounter God in a way that made, made sense to me and made me feel like I was intellectually in control. And so I made it about these books and, you know, and like uncovering, you know, these different faith traditions, but really it was, I think a path to God for me, because I could do it in this kind of contemplative and literary way.

Cole (13m 35s):

There was a lot of bad in it, but there was a lot of good in it. And when I, by the time I went to college, I was like, I I’m really interested in, in Christ. I think, you know, maybe the story of him being divine is a true story is a story that contains truth. Then I started to go to this, this predominantly white, what do you call them? Not a youth group para church ministry ministry, something like that. Yes, the language is escaping me. So I started to go to a predominantly white campus ministry group and continued to ask questions. And after college worked for collegiate ministry organization and eventually worked for an Episcopal church outside of Philly.

Cole (14m 24s):

And that’s where I, I really encountered liturgy for the first time and the, the kind of the solemn nature of a church service and, and liturgy. And I was really drawn to it and have, have been ever since, although I’ll say I haven’t always felt, you know, the greatest sense of belonging in those spaces because I’m because I’m black.

Amy Julia (14m 52s):

Yeah. It’s an interesting contrast between, I mean, I’m thinking about the earthiness or like tan, what you can often a more evangelical and less kind of liturgical space is at least characterized as being more about like an intimate or personal and individual relationship with God and more liturgical spaces are associated with more of that emphasis on some of the abstract qualities of God, the transcendence, the grand jury, the mystery. And one of the things that I find so interesting about your writing and this comes up even in the title of your book is the earthiness and the fleshiness of your understanding, particularly of your Christian faith, not just of, of who God is, but of Christianity.

Amy Julia (15m 44s):

And I would love to hear you talk a little bit about the title, how you came upon the title, but also the way in which you see the words this year flash, which are kind of coming from somewhere. You can tell us about that, but also obviously linked to an experience even of this like bloody scary right. Image of God on a cross. So can you just talk about that a bit?

Cole (16m 9s):

Yeah. So one of my favorite novels of all time is beloved by Toni Morrison and there’s this scene, or are we in, in the novel? We, we continue to go back to the space of the clearing, where there’s this matriarch of all of the people, this black female matriarch, and she’s preaching to all of these women and children and the men who are kind of waiting for her at the perimeters of the clearing. And if you read it, I’m not going to do it justice, but it’s a really beautiful scene because there’s so many unspoken cues and so much embodiment and kind of intuition, but the matriarchs, the matriarch baby Suggs says, you know, children come to the center and then the children come in and she says, you know, let your, let your, mother’s hear you laugh.

Cole (17m 4s):

And, and then they laugh. And then she says women or the men come to the center, you know, like, let your wives, do you dance or let your children see you dance. And, and the men dance and just like women come to the center, you know, and, and cry for the living and the dead just cry. And the women all participate in this weeping moment. And she says, you know, these different generations, all kind of come together and, you know, get tangled up in one another. And the men are weeping and the women are laughing and the children are crying and it’s this emotional embodied spiritual moment. And they clapped in the grass and then baby Suggs gives a sermon.

Cole (17m 44s):

And she says, in this here place, we flesh flesh that weeps laughs flush that dances on bare feet and grass love it. And she goes into this beautiful monologue about the resistance and the necessity of caring for caring for the body and that being a way to care for the soul. So anyways, I, I chose this here flush as a nod to that moment and knowing that my book was going to be this intergenerational storytelling and knowing that I want my spirituality to contain some of what baby Suggs was doing in that clearing.

Cole (18m 27s):

I want that for myself. And I want that for my children and my elders to have that kind of spirituality. I thought that that’s a good place to start, you know, so,

Amy Julia (18m 37s):

Mm. I love it so much. And I, I read beloved for the first time when I was in high school and an English class. And it was actually my favorite book that we read, this was junior year English. And so I went on to take an African-American literature class in college, really, because that was on the syllabus. And I wanted to read it again and I’ve read it a couple of times since then. And I feel like as a white person coming into Toni Morrison’s work in general, maybe beloved in particular, but maybe just in her work in general, I feel like there’s still just a many, many layers for me to continue to understand and puzzle through.

Amy Julia (19m 19s):

And I think some of it is as a Christian, the fleshiness. And I think like that sense of what does it mean to be embodied and to love this body. And on the one hand, I think there’s not a history of hatred related to white bodies, right. In this country. And on the other hand, there can be this like dismissiveness of the body in at least the spirituality that I’ve been raised with. And so for different reasons, I think it’s also been really important for me to understand what it means to have a body before God and to be a body like, yes, I have a soul, but it’s not as though that is in any way, separate from my body.

Amy Julia (20m 7s):

And I don’t even have language to talk about my soul and body being the same. Right. Like being connected. So intimately to one another, that I shouldn’t even have to talk about them as separate entities, but a lot of your book I think is really, and a lot of your work in general is dealing with this sense of what does it mean to be a spiritual body, a, an embodied spirit, like the, these two, what we talk about as aspects of our being, but actually being integrate integrally, linked to each other. And there’s a place where you’re writing about some of your own physical struggles, like in your body and learning how to be friend your body again. So I’d love for you to talk a little bit about what does it mean to be friend our bodies.

Amy Julia (20m 50s):

You can take that in whatever direction you want. Cause I think there are lots of ways it could go.

Cole (20m 55s):

Yeah. I, if you, if you read the book, you’ll, you’ll hear more about this, but I’ve struggled with chronic illness for about five years now and recently more acute issues with my eyes and my retinas in particular. And so I explore what that means, what it means to, to care for, and pay attention to a body that’s in pain a lot. And I think even if you’re not someone who, you know, is chronically ill struggles with chronic pain or is in the disability community, there’s so much you, we, we can learn from, I think the disabled and chronically ill community, because they’ve had to learn what it means to what it means to survive a culture that really succeeds by us being disconnected from our bodies.

Cole (21m 51s):

You know, we’re a lot better being tools for capitalism, for production. What have you, we’re a lot better at that. You make a better tool if you’re disconnected from the pain, from the aches, from the joints, from your needs. And I, I think I can’t afford to disconnect in that same way anymore. And I think you’re right. I mean, you mentioned, you know, the hatred of white bodies has not been as prominent, you know, in the history of our country, but it’s about black bodies, but has everything to do with white bodies too. And I think something I’ve been thinking about, especially in the past few months is what an embodied spirituality could mean for, for white people and, and why the resistance, why the resistance to an embodied faith.

Cole (22m 41s):

And I think frankly, a lot of it has to do with guilt. And when you have to remember your body, when you, as a white person, when you have to remember your body, and when you have to remember your grandma’s body, your great-great grandma’s body and the color of her skin, like that’s going to do something to you. And I think guilt and shame especially is such a driver of what is, you know, motivating people to want to brush quickly over our embodied existence over the, the work and the, the energy of our bodies. Because we, we so much change. Shame is trapped in them, you know, and I can only imagine what that shame would be like for a white person to have that trapped in your body every day and have to remember that.

Cole (23m 26s):

But there, you know, there’s obviously a lot of beauty in our bodies and, and that’s, that’s part of the sermon that baby Suggs is given. She’s saying, you know, like yonder, they don’t, they don’t love your neck on new stint straight. You know, they don’t love that. They don’t love your neck on news. You gotta love it, like stroke your hand on it. And it’s this way of saying, you know, you’re going, this is inherently in resistance to the ideals of the world and the people that want to use you. So, so let’s reclaim it, you know, they’re not going to do it for you. Does that, am I making sense,

Amy Julia (24m 0s):

So much sense? It just, you’re just giving me too many questions because I have to decide on one to go with Nick. No, I I’d love to hear, I’m thinking about the sense of the generational connections, because that’s some work that you do in this book, particularly about your grandma and your dad. That’s really tender and beautiful and filled with grief. Also the stories that you tell of your family. And I wonder how you see that in terms of connection to your own body. And I, and yeah, I think that is one thing that at least in many of the books I’m reading right now, I’ve also been reading the love songs of WB Dubois and it’s, you know, novel, but nevertheless, it is a story of generations and of generations of both beauty and trauma.

Amy Julia (24m 52s):

In fact, it was very interesting reading your book alongside that, because there are so many overlaps, both in terms of the beauty of the writing and the storytelling. But, but I just have been thinking about, in what ways as a white person, do I connect my body, as you were just saying to the bodies of those who’ve gone before. So you don’t need to answer that for me, but I’m curious for you, in what ways do you yeah. Do you connect your body to the bodies of those who’ve gone before you?

Cole (25m 22s):

Yeah, I think I haven’t always, I haven’t always thought about it and the way that I’ve learned to, but it really, when I went to write this book, I, I was planning on writing just this contemplative, you know, like just contemplative meditations on, you know, lament and rage. And, and I, I, I know, well for one, my strength as a writer is in storytelling. It’s was the spirituality of my household growing up. It was stories. And so I, I knew that there was some tension there, but I also realized, I just was incapable of talking about these concepts without talking about stories.

Cole (26m 4s):

And so, you know, I started and then eventually found I’m incapable of talking about, you know, my story of Wilmette without talking about how it relates to my dad’s story of Womack and about, I don’t know, a few years ago I had started interviewing people in my family and my, my father, my stepmother, and my grandma, really just as a family project to continue to, to try to curate some of our collective story and history since that hasn’t been done for us, or I should say that’s a lot of that has been taken from us. And through that, I realized so many threads in our stories that are, that work connected, but I don’t even think my father and my grandmother ever talked about and recognize in themselves these threads of, of stinking, of expanding, of, of hunger, for connection, and then alienation.

Cole (26m 60s):

And there’s a ton of research, more and more research coming out about how, you know, previous generations can affect our DNA. And I suspect it’s just going to continue to come out. I think even before we had the research, we all have known to a certain extent, you know, you know, these personalities, these fears shape us. You know, we pass down our fears from generation to generation, a child sees what their parent is afraid of. And it’s like, you don’t know that that spider is scary until you see someone else, you know, like flinch from it. And so I think we’ve always known it, but now we’re having more and more research to help us give language to what’s happening.

Cole (27m 43s):

I think trauma can be certainly passed down from traumatic the effects of trauma. But I also think a lot of beauty can be passed down in a lot of, a lot of hope and patterns and habits of hope. And, and so, so yeah, and writing this book, I’m uncovering more and more of like how, how, how much I’ve been given, how much I’ve received from both my father and my grandma. Well, then

Amy Julia (28m 7s):

That’s one of the beautiful things about the book is this, at one point when I was reflecting on the book, I wanted to call your dad the hero of the book and he is in many ways, and you even call him a magical hero, I think at some point. And he’s also so very vulnerable and human, right? Like, and, and Fe fallible. That’s the word I’m looking for? Like he is, he is not a perfect person and, and he’s broken in many ways and, and you hold that so well so that you don’t come to the end with any sense of condemnation or of putting him on a pedestal, you know, and just, it’s really, it’s not easy to do that with, you know, characters, whether that’s in fiction or nonfiction.

Amy Julia (28m 56s):

And I think that does hold on to both the, really the breadth of our humanity in the beauty and the brokenness that we all embody in some ways, in various ways. I want to ask a little bit about healing, but before we do, I want to ask one more question, that’s a little more pertaining to spirituality and race early on in the book, you, right. It takes time to undo the whiteness of God. And I was really struck by that sentence and would love to hear you reflect on what it has meant for you to undo or begin on doing the whiteness of God. Yeah.

Cole (29m 34s):

Yeah. I’m glad that you, you paused at that sentence. Cause I, it was a sentence that I thought, should I just take this out? And I I’m, you know, so I was raised most of my life and not an inherently religious home. You know, I started possessed a kind of spirituality, but not a Christian, an overtly Christian spirituality and somehow, and in between, you know, that, that white Baptist church I attended and that predominantly white campus ministry that I attended at some point, the image of a white God was injected in me. And you would think, you know, you weren’t raised with this, you weren’t raised with this image.

Cole (30m 17s):

I wasn’t even raised thinking about Jesus. So like, why is this so like stuck in you? And I think once it’s in you, it takes time. It’s more than me just saying, you know, you know, God is, God is black. God is black. And I in the book, I say, you know, even still after years of trying to deconstruct, and I know that word is difficult for some people. So me vision youth deconstruct, but even after years of trying to reclaim my sense of spirituality and who God is and telling people, person after person called and after college student, you know, God is not white. God is not white. I still sometimes think often think of Jesus as white. What does that mean? It’s like, I it’s, it’s really, it’s really sinister image that it’s, it’s difficult to get out of you, especially when so much in art and other things can affirm that.

Cole (31m 6s):

Or at least the art that we elevate can affirm that. And so what it’s looked like for me is finding a community of belonging that will not let me go. Even if will not reject me, I should say, even if I come to different conclusions than them, even if yeah, I community that gives you the freedom to explore and question and resist, I think is it’s frankly, the path to young people in this time, it’s the path to young people who feel so skeptical and so trapped in smothered by Christians telling them what to think and believe about everything, as opposed to letting them experience their belief and experience God and give them time to work out what God means for them.

Cole (31m 59s):

So when my belonging depended on believing in a white God depended on believing in a God who was indifferent to black suffering or who didn’t center black suffering or all of these things, you know, my faith, my faith and my experience of God was so small. I would say I w I was barely experiencing God. I was more so experiencing this desire to belong, to fit into these spaces that ultimately didn’t love me or care for me being in spaces of true belonging that say, regardless of what you w you know, belief you reach, regardless of what doctrine you come to, like we need you.

Cole (32m 39s):

And, you know, and it’s this community of mutuality and tenderness. That’s how it happens. You know, people say, read this book, read that book, and I’m a reader. So I’m never going to say don’t do that. But I think more than that, it’s like find people who you feel safe to ask questions with. You know,

Amy Julia (33m 0s):

That’s really interesting. And I love that. I’m thinking too, because I think it’s actually important for different, again, for different reasons, but for white Christians also to undo the whiteness of God. And I th in all of these conversations, there’s a sense of the incarnation of God in Jesus, does affirm the ability to find God in people who look like you, whoever you are, right? Like there is some, whether you’re white or black, that’s not what we’re talking about in terms of like undoing the whiteness of God.

Amy Julia (33m 40s):

But in terms of undoing the idea that a God is only represented in a physical whiteness, but also all that whiteness has come to represent historically, as far as power. And even within our culture, like some idea of goodness or beauty, or, you know, any of those types of things. And recognizing that, in fact, where the God of the Bible introduces, I mean, in the Psalms, God says, you know, essentially let me introduce myself. I am the God of the poor and the oppressed and the widows and the orphans and the strangers, the people who are not Israelites.

Amy Julia (34m 22s):

And you’re like, wait, what, that’s how you, that’s your calling card? You know, and I think there there’s so many facets, at least to what it means to actually understand the vastness of who God is and the mystery, and also that particular intimate experience of a God who knows you as you are. And anyway, I appreciate your willingness to wrestle a little bit with that. That’s certainly something I’ve been wrestling with as well. I’ve also wrestled with, and I think this also goes back to artwork, but I remember the first time I had the thought that Adam and Eve, whether we think of them as like into individual humans, or even in some sort of representative state, we’re not white, I literally was like, oh, I mean, of course, like even just geographically, that makes absolutely no sense.

Amy Julia (35m 17s):

But I was so like when I came to that thought, and it’s such a good thought exercise in terms of just UN peeling back my own unspoken assumptions about who belongs right. And who is represented and who God sees and who God cares for, which is again much farther and wider and broader and deeper than I might even be able to imagine. Yeah,

Cole (35m 44s):

That’s good.

Amy Julia (35m 46s):

Well, I do want to make sure I get a chance to talk to you a little bit about healing, because you write about woundedness and you write about trauma and you write about pain, but you’re also writing about healing. And I’m curious to hear just ways in which you say you have experienced healing and also where there might still be some longing for healing where healing has not been kind of neat and tidy or complete.

Cole (36m 13s):

Yeah, absolutely. I think I’ve experienced a lot of healing in, well, I’ll speak to me personally, and then maybe I’ll try to apply it to more people, but, but I personally have experienced a lot of healing in literature and people that have gone before me and novels and fiction, I found so much, so much healing and the imagination of, of black people for kinds of healing. And I think that speaks to me because of there’s something true about my interior life, about myself hood, you know, like I, I am a person who loves literature. So, you know, it makes sense for me to experience healing in that way.

Cole (36m 57s):

I think it’s, yeah. I feel like we’re in this kind of space a lot. So social media space where we’re trying to find this kind of one fits one size fits all path to healing for, for so many people. And it’s, I don’t want to be too hard on it, but I think it really can. It can a be kind of lazy, a lazy form of caring and, you know, helping people towards healing. But, but also it’s, it’s just not true. And sometimes I just want to, like, I use my, I don’t have a smart phone. I use my husband’s phone and sometimes I just want to throw his phone and be like, this is, this is not going to work.

Cole (37m 41s):

Like you can’t just take five. Not everyone can take five deep breaths. And like, you know, it feels like there and drink a glass of water and feel like they’re ready to go. Like it’s different for different people. And certainly I think everyone can glean something from like breath and caring for your bodies through water. I’m not saying that, but I’m just saying, allow your path to healing to be nuanced and to make sense with your true selfhood. And that requires some interrogation of the self, that it requires a lot of interrogation of your interior life to say what the desires are in me. You know, what fears are in me. And, and one of, I felt one of, I felt connection. I feel connection in books, you know, encountering these characters or talking to other people about books.

Cole (38m 26s):

And so if that’s the path for me, that’s, it’s going to be literature, but it might be something else for, for someone else. I also think you’re completely right. This kind of tension of knowing, like there’s always more healing that can happen, and that can lead to really dissatisfied souls. If you’re expecting to just like, be fully healed. Like, I, I, I say, you know, I’m moving toward liberation. I want us to move toward healing, move toward liberation because I’m just really not certain if I’ll ever experience a sensation of like full healing. And I think that’s okay. And I don’t mean that to sound despairing.

Cole (39m 8s):

I just mean that I hope that we, as humans can learn to be more acquainted with like the, not yet, you know, and, and the waiting and the fact that we’re, we’re healing as we’re constantly being wounded and we’re healing as we’re constantly remembering old wounds that we have forgotten about my grandma she’s since passed since writing the book. But one of the last conversations we had, we had been talking about healing. We had been talking about each other’s stories and she said, this that I think will stay with me forever.

Cole (39m 48s):

She’s she, she, she might not even remember what you were saying or known what she was saying, but she’s talking about our story. She’s talking about my story and like using we and I, and you interchangeably. So I didn’t even know who exactly she was talking about. And then she just looked at me and said, we did good. We did good. We took the sweetest part of the fruit and we cut it off. Wow. I know I walked out of that hospital room. I was like, I looked at my husband and I’m like, did you just, did you hear what she said? And I looked it up because I thought there’s no way she just thought of that in that moment. But she did, we did good. We took the sweetest part of the fruit and we cut it off.

Cole (40m 30s):

And so there’s so much mystery in those words, but also something, something very incomplete. Like we, we, we shouldn’t say we did our best, you know, she didn’t say like, we’ve made it, it wasn’t like a triumphant, it wasn’t triumphant language of healing. It was just like, we did good. We took the sweetest part of their fruit, which means that, you know, that that’s an acknowledgement that some of that fruit was poison. You know, we shouldn’t take the poison fruit. We took the sweetest part of the fruit and we cut it off. And we said, you know, what does it look like to, to also behold the beautiful and be able to understand that like your fruit might contain both a strangeness and a beauty and a goodness.

Cole (41m 15s):

And so that’s, that’s wisdom from Phyllis, Phyllis, Marie, Arthur, not from Kohler, but I definitely have been past. Yeah.

Amy Julia (41m 25s):

Yeah, absolutely. I, you know, it’s interesting cause I’ve, I’ve been thinking a lot about the idea that our body can tell us, like, Hey, pay attention. Like that ache in your back is actually a signal of the, you know, stress that you’re feeling about such and such, or, you know, there are ways in which we can, if we pay attention to physical hurt, actually get to some emotional and spiritual woundedness and be healed of it. But also I’ve been thinking about chronic pain and that there can be this easy narrative of like, oh, you just haven’t paid attention to the wounds that need to be healed and your inner being. And so it’s essentially your fault that it hurts. And like, I’m like, okay, that, and, and yet I do think there’s some measure of, there is always pain in the world.

Amy Julia (42m 12s):

And our bodies sometimes reflect that in such a way that it can come up for healing, so to speak. And sometimes we are bearing witness in our very bodies to that, which is wrong. And that might be wrong. Something that has literally happened to us that is wrong, but it also might be something that is just like wrong in the universe, like wrong in the world, at least for the time being and carrying pain and acknowledging that and not, and not pretending that it’s gotten all better, might be a way of saying, yeah, it’s not all, it’s not all. Okay. I think even in your book, you write about Jesus weeping for Lazarus. And I wrote down this quote to, you said, if Christ wept for Lazarus, he must have done.

Amy Julia (42m 56s):

So not out of an absence of hope or faith, but out of love, it was an honoring when we weep for the conditions of this world, we become truth-tellers in its defense. And I think about pain sometimes being similar, like it could be an, it could be an alert like, Hey, you need to pay attention and do something. But what if it’s also sometimes an honoring and a weeping for the conditions of this world that comes out in our bodies. So within all of that, I think you write about the role of sorrow, the role of lament, the role of rage, essentially in healing, like as a part of an honest expression of faith, but also as a part of a necessary pulling back, if it’s going to be a time to actually allow God in to healing.

Amy Julia (43m 49s):

So I’m curious if you could just speak a little bit to yeah. Sorrow, rage, lament, hope, healing, all those things.

Cole (43m 58s):

Yeah. I think all of when I think about hope, at least I think it means that you have an imagination for something different. And whenever we weep, whenever we’re angry, I think there’s some kind of, it’s, it’s some kind of inherent acknowledgement that you expected, or you desired something different that you had an imagination for a different way. You know, I’m angry whenever, you know, someone, I don’t mean this to sound trite, but it’s just an example. I’m angry when someone cuts me off in traffic because I have hope, and I have this imagination and expectation that people will, you know, be caring and, you know, tender on the roads or however you want to look at it.

Cole (44m 40s):

But there’s, there’s something of that emotion that I think is inherently rooted in, in hope. I mean, despair and violence, you know, those are different. That’s when you know, the little meant in the rage kind of flip into something that’s degenerative as opposed to something that is leading toward a better way or pointing toward a better desire or a more whole desire. So I think they’re really important and they’re, you know, frightening and all obviously always going to threaten people who hold way too much power who want us to focus on positivity all the time.

Cole (45m 23s):

But I, I try to remind myself as much as possible that, you know, whenever I am giving myself the freedom to experience pain, to name, aches, to name my anger, I also can make it, you know, pointed in the direction of hope and, and to, to claim, to, to use my limit, to claim. I want more for myself. I thought, I, you know, I, I say, you know, lament, it’s, it’s, it’s not about the world being bad. You know, I think that’s the people say, it’s like, you’re just saying the world is all bad. It’s no, it’s about, it’s about believing that the world is worthy of goodness that my neighbor it’s worthy of goodness. That’s where the sadness comes from.

Cole (46m 3s):

And if we shift that, I think those emotions can be experienced as a form of hope.

Amy Julia (46m 9s):

I really appreciated your words along those lines in the book as well. Thank you for sharing that here. And I’m as we come kind of to the end of our time, the last question I wanted to ask you is just the way in which you see a relationship between personal or individual healing and caring for the body and like kind of accepting the body’s limitations as, and beauty and goodness and social healing, the work of justice and of activism and yeah. Bringing that healing into the world. How do you see those things as related to each other?

Cole (46m 46s):

I, I think that we’re reaching a point where we’re putting a lot of weight on self-care and self-awareness, which I think has value. There’s the Audre Lorde quote that, you know, people post all the time or share all the diamond, these dogs about self care, being an act of, you know, political resistance and that, and I, that’s a beautiful thing. Don’t stop sharing that quote. But at the same time, I think we have to reach a point or we have to be inclusive of language of community care as well. There’s, you know, sometime not sometimes self care is just never going to be sufficient.

Cole (47m 25s):

Self-awareness is never going to be sufficient. I think we were made for a lot more than that. We are made for this kind of communal care, communal attunement, and I can care for myself all, you know, all I want, but if, if my neighbor doesn’t love me, I’m still going to be wounded and wounded and wounded. And then what am I supposed to do? Take a bubble bath. And then the next day I get w like, that’s not how we’re going to get free. You know, that’s not the path to liberation. I, I fully believe we need to have, you know, an imagination for the individual and the collective and to not alienate them from each other to know that, you know, receiving community care can be a form of self care and to kind of have those things like intermix in, in a more meaningful way.

Cole (48m 13s):

And then I think that expands out of the community care out of the individual, the care for the individual, for the individual, we can expand into social healing. You know, we can expand into, into policies into infrastructure, but I, I think that this, the self care and the collective care community care, that’s where things begin. They’re kind of like these groundworks for social imagination in general, at least as I think about it. I’m curious how you think about it.

Amy Julia (48m 44s):

Well, yeah, I do think so. I guess I’ll say two things. One, what I’m hearing you say is that actually connecting with other humans is in an intimate and loving way, right? Like is an act of self care like that. There’s actually not, I mean, we might distinguish them because of the way self-care is written about and spoken about, which is take a bubble bath or take your deep breaths or whatever it’s like seen as this solitary endeavor. And not to say it shouldn’t be, I think you and I both are people who will take care of ourselves by curling up with a book almost daily, but at the same time, that sense of like, no, no, you need other people.

Amy Julia (49m 25s):

And that’s an aspect of self care. And when I’ve also my own experience of yes, like participation in the work that I believe God is wanting to do through us in the world has almost never been solitary. Like, I mean, I’m trying to think of an example. It’s like when I’ve committed to praying with someone else that I’ve even had the eyes to see places where I might be able to be involved or have had the courage to go to March or have had the wisdom to talk to my children in a different way about what events we’re seeing on the news. I mean, whether it’s these very little things within our home or much broader political participation, I also, some of the work I’ve been doing around healing has been looking at Jesus in the gospels and his healing work always is sending people back into their communities for the, with a blessing that involves the idea of Shalom.

Amy Julia (50m 29s):

So, you know, the bleeding woman, he says, go in peace. Like he literally sends her publicly proclaimed, her healed. So her community can receive her. And then those words that can seem kind of trite to us, go in peace. I mean, he is as a Jewish man saying, bring, show them with you where you go bring the healing of the healing dream of God, right with you as you go back into your community. So I think that there is always a connection for true healing to be taking place. There’s always going to be a connection between that self community and society and an even broader way. That’s beautiful.

Amy Julia (51m 10s):

We’ll call your words are beautiful and powerful. And that is true both in terms of black liturgies on Instagram, as well as in your book this year flash, which I am just really grateful to have been able to read and talk to you about. So thank you for joining us here today. Thank you for having me. This has been great. Thanks so much for listening to love is stronger than fear. Remember to check the show notes, to learn how you can enter for a chance to win a copy of this here, flesh, and to visit my website. I’d love for you to read an excerpt from my book to be made well and check out the gifts that I can send you.

Amy Julia (51m 51s):

If you order the book before March 15th, when it comes out and as always, I would love for you to share this episode, subscribe to this podcast, give it a quick rating or review so that more people can benefit from these conversations. Thank you to Jake Hansen, for editing to Amber Berry for doing all of the social media coordination. And thank you to you for listening as you go into your day to day, I hope and pray that you will carry with you. The peace that comes from believing that love is stronger than fear.

[podcast_subscribe id=”15006″]

We’re giving away a copy of THIS HERE FLESH: Spirituality, Liberation, & the Stories that Make Us. To enter, complete the following 2 steps:

- Follow Amy Julia Becker on Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter.

- Share this podcast episode on one of those social media platforms and tag Amy Julia when you share OR find this episode’s post on one of Amy Julia’s social media accounts and comment about why you would like to win this book or tag a friend!

Thank you to Convergent Books for the giveaway. Shipping to continental US addresses only. This giveaway ends on Saturday, March 12, 2022, at 11:59 pm EST.