Our family took a short civil rights tour through the southeast that included stops at a plantation in Louisiana and various sites and museums in Montgomery, Selma, and Birmingham, Alabama. As we look ahead to Martin Luther King Day, I’m thinking back on what our trip taught us about our history, our present moment, and how we can participate in love.

The Hub of Our Civil Rights Tour

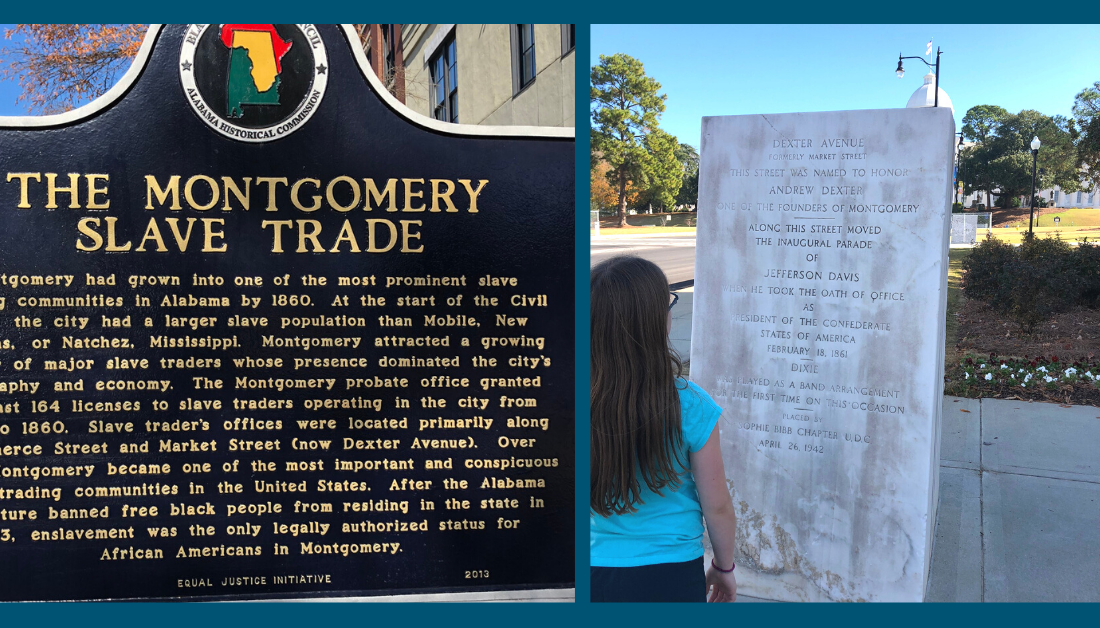

It was Saturday, November 30, and we were in Montgomery, the hub for our “Civil Rights tour” through the southeast. We set out with a guidebook and started reading placards that lined the sidewalk: Here is the site of the slave market. Here is the site of the bus stop where Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat. Here is the spot where a telegram was sent that began the Civil War. Here is a timeline of Civil Rights history. Here is the capital building, a mammoth structure of white marble at the head of the main street, to which protestors marched from Selma, 45 miles away, to advocate for voting rights. And here is Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Junior’s first pulpit, a small brick church one block away from the halls of power.

As we approached this church, Dexter Avenue Baptist, we noticed people gathered out front. We soon learned they were celebrating Rosa Parks’ Day. One woman invited us to join.

We stood among a crowd of mostly African American Christians and listened to a sermon about Esther (who, like Rosa Parks, was an unlikely hero, the concubine of the king of Persia risking her life on behalf of the Jewish people). We listened in awe to the powerful voice of a woman who initiated the march with the words of a mournful Negro spiritual, “Hold On.” This call to persevere carried into the street as a reminder that as much as there is to celebrate when it comes to civil rights in America, there is still a long way to go.

A Few Days Earlier – Whitney Plantation

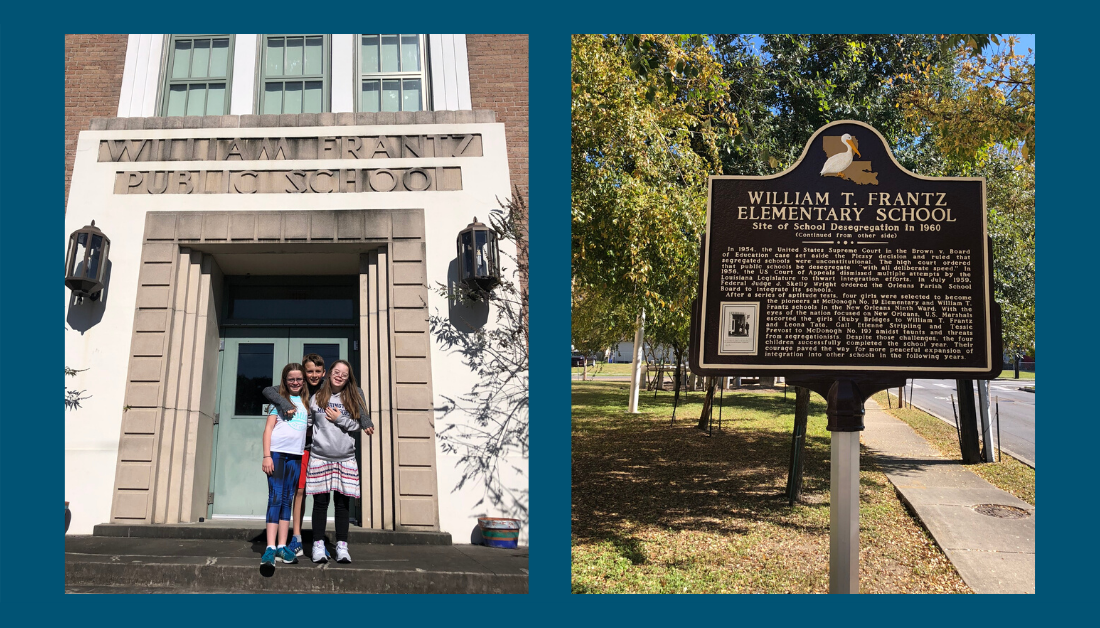

A few days earlier on our civil rights tour, we had visited the Whitney Plantation, a site 45 miles west of New Orleans designed to tell the story of the majority of the people who lived and worked there—enslaved African men and women for the first fifty years of its existence, then sharecropping African American farmers who remained for the next century.

I learned later that scholars have begun to call plantations “forced labor camps” because those words are more accurate ways to describe these sites and how they operated for hundreds of years. Still, many are now tourist attractions. Our hotel in New Orleans featured a brochure with a white woman in a white dress with a small hoop skirt and a white parasol. The image alone was an invitation into a fantasy land from long ago, when white masters enjoyed balls and parties and were waited on by polite and contented “servants.”

Marching in Montgomery

This march down the streets of Montgomery, with the tone of both celebration and mourning, was a fitting next step in introducing our family to the history of African American people within the United States. When Rosa Parks stayed in her seat in the 1950s, it was nearly one hundred years after emancipation, and African American people did not have the right to seats on public buses or to cast votes in local elections.

As we marched, a part of me felt like an imposter—who was I to stand shoulder to shoulder with these women and men? I was a white moderate from the North who had never marched for any cause. I was a woman who had never felt the sting of injustice or prejudice directed at me. We were a family whose history does not contain rejection or oppression.

The woman marching next to me struck up conversation. She had noticed William’s sweatshirt with the name of his Montessori school. This woman’s daughter had been in a Montessori school for years, so we shared stories about why we loved what it offered for our kids. I did not deserve to be on this street, honoring Rosa Parks, having this conversation. But we were included. We were welcomed.

Civil Rights Tour–Selma and Birmingham

That afternoon, we learned the history of the bus boycott. We drove to Selma and walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where the march for voting rights began, where men like John Lewis faced the brutality of a mob of policemen.

The next morning, we traveled to Birmingham on our civil rights tour and attended worship at the 16th Street Baptist church, site of the 1963 bombing that killed four young girls.

It all progressed like a story, from enslavement to Jim Crow and lynching, to the NAACP and Dr. King’s introduction of nonviolent resistance in the name of love, to the bus boycott and protests in Birmingham and Freedom Summer, and then this bombing.

Peter and I had learned all this history in school, and we had heard it repeated for years in articles and books, but it was different to be there in person. Yes, it was different because of what we saw: the black patent leather shoe of one of the girls who died, a stark reminder of her innocence in the face of hatred; the juxtaposition of the monument to Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy, and the monument to Martin Luther King and the Voting Rights March; the videos and timelines and testimonies that stitched together the disparate events into a story.

Civil Rights Tour–Being Physically Present

But it was also different because being physically present directed our attention. For four days, we paid attention to the story of African American people in Louisiana and Alabama, and it changed the way we see ourselves.

The Whitney Plantation allowed us to imagine the experience of enslaved Africans two hundred years ago. It prompted us to think about Peter’s family—white farmers in Louisiana who owned enslaved people. It was hard to deny the generational impact of those divergent stories, impossible to deny that we had received economic benefits from the brutal treatment of fellow human beings, and that those repercussions could be felt to this day. And then the monuments and museums articulating the struggle for basic equal rights as Americans reminded us of our shared humanity with these ordinary heroes, these men and women struggling in the name of Jesus, for freedom.

Trip Conclusion

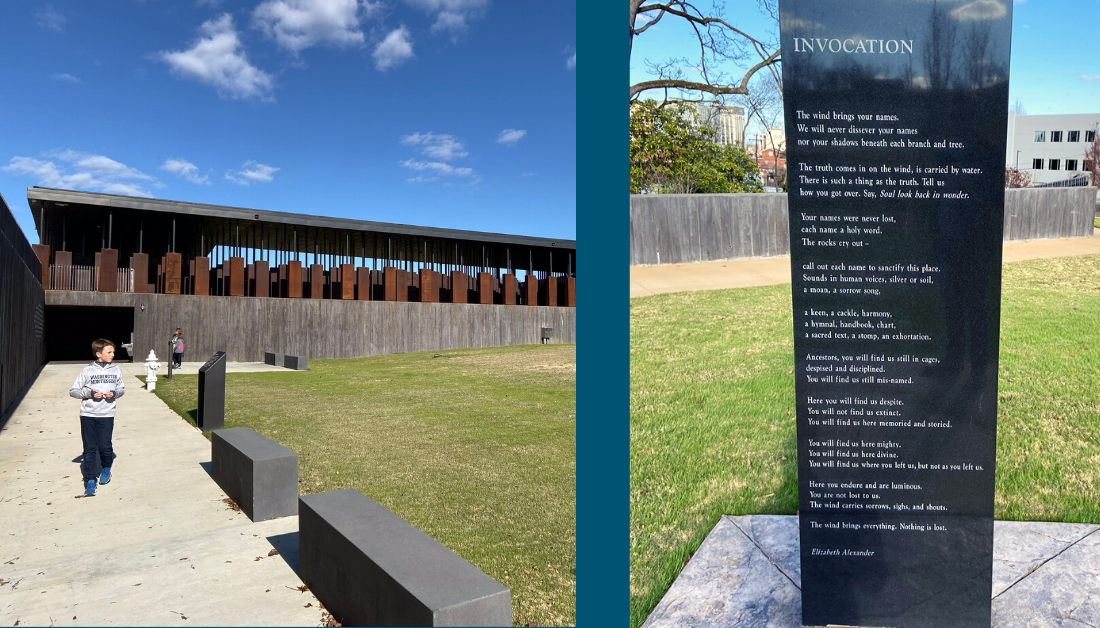

We concluded our civil rights tour at the Memorial for Peace and Justice, which commemorates the thousands of women and men who lost their lives to lynch mobs across the nation.

And we visited the Legacy Museum, which not only tells a complicated and disturbing history of enslavement but brings that legacy to the present day and specifically to the unjust workings of our criminal system.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. insisted repeatedly that the subjugation of African American people harmed everyone. Because it so violently and irrevocably demeaned and distorted the personhood of the black women and men and children in its grip—and because it did so purely for profit and power, out of fear—it also necessarily distorted and demeaned the white masters and the white onlookers. It warped everyone. With Peter’s heritage from Louisiana and mine from Connecticut, we represent both the masters and the onlookers.

We left not just acknowledging the harm of the past, but with a conviction that we need to reckon with that harm personally.

Justice is Love

In his speech about the Montgomery bus boycott, Dr. King said, “It is not enough for us to talk about love… There is another side called justice. And justice is really love in calculation. Justice is love correcting that which revolts against love.”

Justice is love correcting that which revolts against love.

Taking this trip was one step closer to correcting all that revolts against love in my own soul, in my own community, and in this nation. The call to seek justice, the call to acknowledge the brutal pain and evil of our past, the call to work against ongoing injustice, the call to give of time and money and energy towards healing–it is not a call for punishment, guilt, or shame. It is a call that invites us, much like the men and women marching through the streets of Montgomery, to participate in love.

If you haven’t already, please subscribe to receive regular updates and news. You can also follow me on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.