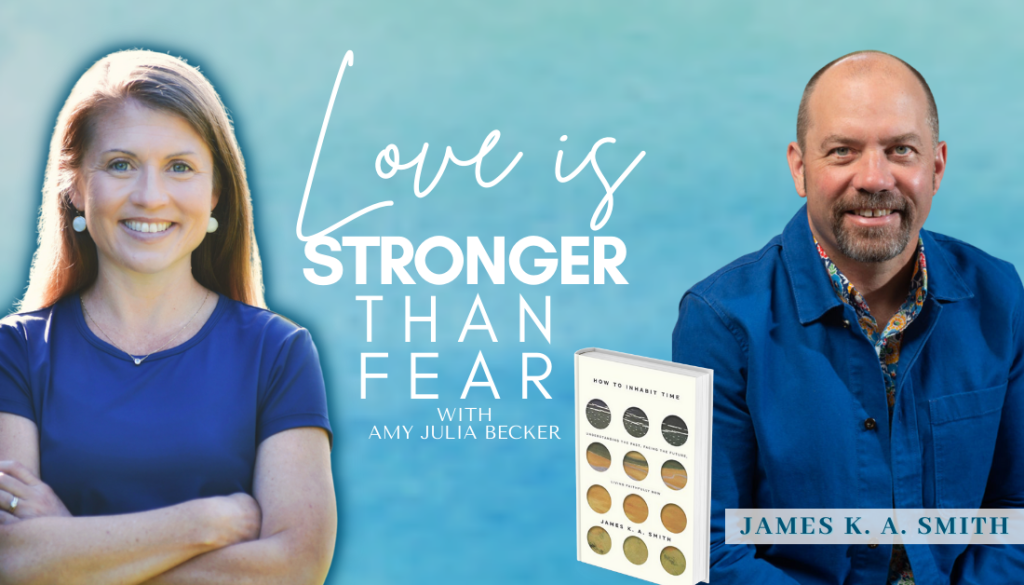

Do you feel like there isn’t enough time or wish you could just get a better hold on time? This episode is a chance to enter into a way of greater freedom with time. Professor and author James K. A. Smith talks with me about history, contingency, limitations, Black Lives Matter, hope, and his latest book, How to Inhabit Time: Understanding the Past, Facing the Future, Living Faithfully Now.

Guest Bio:

“James K. A. Smith is professor of philosophy at Calvin University and serves as editor in chief of Image journal, a quarterly devoted to ‘art, mystery, and faith.’ Trained as a philosopher with a focus on contemporary French thought, Smith has expanded on that scholarly platform to become an engaged public intellectual and cultural critic. An award-winning author and widely traveled speaker, he has emerged as a thought leader with a unique gift of translation, building bridges between the academy, society, and the church.”

Connect Online:

- Website: jameskasmith.com

- Twitter: @james_ka_smith

On the Podcast:

- Latest book: How to Inhabit Time: Understanding the Past, Facing the Future, Living Faithfully Now

- Christianity Today interview with Bono

- Bono’s book Surrender

- Midnight Library by Matt Haig

- Repetition by Kierkegaard

- Plough Essay | When Merit Drives Out Grace

- A Royal Waste of Time: The Splendor of Worshiping God and Being Church for the World by Marva Dawn

Interview Quotes

Quotes are edited for clarity…

Lament is lament because it’s haunted by hope.

Time management treats time primarily as a commodity and also treats it as if time is just something that is out there for me to control and master. Whereas what I’m talking about when I talk about spiritual timekeeping is really starting to recognize the histories that live within us and becoming aware of the sort of body clock, if you will, in an incarnate sense of the fact that we are these creatures who are shaped by time, immersed in time. That it’s precisely why time is never something that you could just manage because it’s not something out there over which you could be master. Instead, time is like the water we swim in as creatures. So we need to learn how to swim, not how to control. And I think that means accepting a lot of things about our creaturehood.

If I was going to be whole and healed, I needed to reckon with my past.

The whole point of the reckoning is to be able to live forward in hope. And I do think that that is part of where a Christian or redemptive imagination has a gift to offer our wider culture. I think there are versions of looking to the past that basically think that we are only, entirely victims of what has come before, whereas there has to be a possibility of a self-transcendence of that history. And I would say that’s the mystery and gift of the possibility of grace. I do think reckoning with our past is confronting the shadows and the things that we’ve buried, but it is also turning back to receive the gifts that have been handed down to us as possibilities, even if they have been latent or we haven’t picked them up.

One feature of this kind of spiritual timekeeping is an awareness that to be human is to inevitably be the kind of creature who remembers and is indebted to a past and also a creature who lives leaning forward and is in some way oriented to a future. So we’re always stretched between these, but how we remember and how we live forwards is what’s at issue. Nostalgia is such a powerful narcotic in our culture right now.

If Christians wanted to be gifts to their neighbors, we could try to live out how and why it looks different to live hopefully, which is a lot harder than it sounds.

The intimacy and specificity of God’s being with us to gather up each of our particular wounds and to reckon with, by grace, the traumas that we’ve endured. And so that grace and redemption are not just these reset buttons so that you erase what’s gone before…It’s not that we all start now as these generic Christians who have this new life. It’s in fact me, with all my particular hurts and harms and histories and gifts and talents and the history that I have lived through, is part of what God gathers up now and rereleases.

Here are all the gifts that have been handed down to you. And the question now is what are you going to do, how are you going to pick those up gratefully in such a way that you accept limitation? I really do think to remember the distinction between creature and creator is to accept our finitude, to accept our mortality, to live with our limitations and to then realize still how much is possible within those limitations.

When we’re talking about wasting time…we’re talking about wasting time relative to what a cult of efficiency tells you. And we’re always talking about wasting time with others. The more we imagine our timekeeping tethered to friendship tending, the more we will…learn how to inhabit time faithfully.

Season 6 of the Love Is Stronger Than Fear podcast connects to themes in my latest book, To Be Made Well, which you can order here! Learn more about my writing and speaking at amyjuliabecker.com.

*A transcript of this episode will be available within one business day on my website, and a video with closed captions will be available on my YouTube Channel.

Note: This transcript is autogenerated using speech recognition software and does contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

James (4s):

When we’re talking about wasting time, Marva Marva Dawn wrote a book on worship called A Royal Waste of Time, which I, i, I think is really, really brilliant. We’re talking about wasting time relative to what a cult of efficiency tells you. And we’re always talking about wasting time with others. The more we imagine our Timekeeping tethered to friendship tending, the more we will sort of learn How to Inhabit Time Faithfully.

Amy Julia (40s):

Hi, Friends. I’m Amy Julia Becker, and This is, Love is Stronger than Fear A podcast about pursuing hope and healing in the midst of personal pain and social division. Today I am talking with Jamie Smith about Spiritual Timekeeping. You may know Jamie Smith. He goes by James K A Smith on his many, many books. But the book that he’s just written is all about time. And so it seemed fitting to have this conversation at the end of the calendar year and near the beginning of the liturgical year. And if you aren’t familiar with the idea of a liturgical year, it’s something we’ll talk about on the Podcast. But the reason I wanted to have this conversation now is for any of you who are like me, often feeling that there isn’t enough time and you wish you could just get a better hold on time.

Amy Julia (1m 29s):

This episode, as we enter into a new year, is a chance to also enter into a way of greater freedom with time. We talk about history and contingency and limitations and Black, Lives, Matter and hope and disability and slowness and love, and so many other good things. I hope you enjoy this conversation as much as I did. Well, I am sitting here today with Professor James K, a Smith, also known as Jamie, and the author of a number of books, a number of books that I have read and valued and really appreciated. Although today we are just here to talk about the most recent book that I have read and appreciated.

Amy Julia (2m 10s):

and that one is called How to Inhabit. Time Understanding the Past Facing the Future Living Faithfully Now. So Jamie, thank you so much for being here with us today. Oh,

James (2m 20s):

It’s my pleasure. It’s great to see you again. Good to chat. Thank you. Hmm.

Amy Julia (2m 23s):

Well, I was so intrigued by your book because you’re pretty clear really quickly in the opening pages that yes, this is a book about time, but it is not a book about time management. And in fact, it’s a time about what you ca a book about, excuse me, what you call Spiritual Timekeeping. And I would really love to have, just to jump in with a definition or an explanation of Spiritual Timekeeping and also how is that different from time management? Yeah. Like why, why need, why do we need to really almost divorce those things, concepts from one another so quickly in this book?

James (2m 58s):

Yeah, that’s, that’s a great place to start. I think. I, I think time management assumes a way of relating to time that I want to challenge. So that’s why I want to do something else. And I, and I think time management is, it sort of treats time primarily as a commodity and also treats it as if time is just something that is kind of out there for me to control and master. Yeah. Whereas what, what I’m talking about when I talk about Spiritual, Timekeeping is really starting to recognize the, the histories that live within us and becoming aware of the, the sort of body clock, if you will, in an incarnate sense of the fact that we are these creatures who are shaped by time, immersed in time.

James (4m 2s):

That, that it’s precisely why time is never something that you could just manage because it’s not something out there over which you could be master. Instead, time is like the water we swim in as creatures. Hmm. And so we need to learn how to swim, not how to control. And I think that means accepting a lot of things about our creature hood, really.

Amy Julia (4m 30s):

And I am struck by a quotation early on in the book you wrote, we don’t need coaches who will help us manage our time. We need prophets who make us face our histories. And I wonder if you could speak a little bit to that, that it’s that sense of facing our history as a really essential aspect of swimming in time.

James (4m 51s):

Yeah. And this is, and and you, you will have seen in the book, I don’t know if I’m a little greedy in what I try to do in the book, but I try to, I, I, I think all of this holds true both on a personal and individual level and on a collective and communal level. So all the same dynamics, sort of like I can, I can grapple with these things for myself, but I think we, yeah, this us, whatever that us might be, needs to grapple with these things. So in, in my case, You know, a real catalyst for thinking about these matters was my own experience in therapy and counseling and what I discover, which, which turned out to be a really intense and significant Spiritual journey.

James (5m 42s):

And I would say the, the thing that I maybe learned the most significantly was that if I was going to be whole and healed, I needed to reckon with my past. I needed to sort of face and grapple with and reckon with the history that I had un undergone as, as a person, as a son, as an individual. And so that, that sense of the prophetic moment, I think is about this reckoning with our past, which means that sometimes we need people to show it to us because we happily turned a blind eye to the parts that we don’t want to face.

James (6m 24s):

So the, the other thing that was going on when I was really starting to work on this book was the murder of George Floyd by police. Yeah. and that was such a, a catalyst. Again, we said, You know this always has to keep happening over and over and over again, the United States. but it was a catalyst again for a kind of collective, even national reckoning, again, with a past that I think we all too happily would bury in the basement and ignore. And it was sort of prophetic voices that were calling us to, to face that past. So that’s the sense of, and and it’s interesting, I do think that that’s sort of a biblical notion of the prophetic as well, the right that the pro often what the prophets do is sort of call God’s people to confront what they would rather not.

James (7m 17s):

And often that’s about You know where they have gone and how they have gone astray, but it can also be how they’ve been harmed and delivered. And recalling that too. I don’t know. I, I feel like I’m, I, I don’t want to ramble too long about that, but does that help?

Amy Julia (7m 32s):

No, it totally helps. And there are a couple threads I wanna pull on a little bit because I agree with you that they’re, for me, and maybe this is because we live in such an individualistic society, understanding, healing, healing on a personal level, which kind of inevitably involves the past and reckoning with the hardest things, things that you, that I had wanted to cover for so long because it felt like, why would I ever go back there? I, it hurt. I don’t wanna go back there. And yet, going back to that pain and, and really essentially bringing it into the light of God’s healing is the only way for that pain to not just continue to be carried within, not even just my spirit, but my body.

Amy Julia (8m 12s):

And you write about this as well, how much we literally carry these things. And that’s been really helpful for me. And thinking about our collective pain as a nation that is so embedded in our history, especially as it pertains to both indigenous peoples and You know the African American beginning obviously with enslavement and then continuing to this day. And I think that’s similar, just as I say, well, I don’t wanna look at what hurt when I was in high school because who would relive something if you don’t have to, I You know and yet needing to do that. I think that’s really similar to what we need to do on a conscious collective level, especially as white people.

Amy Julia (8m 52s):

Although it’s true, I think for all of us in the sense that whether you have been on the side of kind of perpetrating harm or receiving harm, everyone’s been harmed in that process. There’s, there’s a, a pain that needs to be reckoned with. And yet I think one of the, the reason that being prophetic about it is important is essentially the, the hope of redemption, the hope of healing, the idea that facing our history is actually a hopeful forward looking possibility You know realm of possibility. And I think you write to that, speak to that in your book as well, just that that sense of this is not for the sake of feeling bad about what happened in the past, but actually for the sake of the healing or redemptive work that might be able to happen.

James (9m 38s):

I’m glad, I’m so glad you sensed that because that’s exactly right. That, that the whole point of the reckoning is to be able to live forward in hope. And and I do think that that is part of where a kind of Christian or redemptive imagination has a gift to offer our wider culture. Cuz I think there, there, I think there are versions of looking to the past that basically think that we are only in entirely victims of what has come before, whereas there has to be a possibility of a self-transcendence of, of that history.

James (10m 22s):

And I would say that’s, that’s the mystery and gift of the possibility of grace. I mean, it’s interesting, I do think reckoning with our past is confronting You know the shadows and the things that we’ve buried, but it is also turning back and to receive the gifts that have been handed down to us as possibilities, even if they have been latent or You know we haven’t picked them up. And in that respect, I mean, I really do think that, say Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. Is an exemplar of this dynamic that you’re talking about, which is, on the one hand, You know prophetically needs the United States to confront its history, but it’s not actually to just sort of wallow in guilt or even sort of like get a perverse pleasure out of how guilty we feel, which is a strange dynamic today.

James (11m 18s):

Yep. The whole point is to say there’s also possibilities here. You know there have been checks that have been signed that we haven’t been able to cash yet. And so I think that that’s precisely why you can then imagine a different future. And I, I think that’s true on a personal level too. Like you You know someone who, who’s suffering from, from really darkened depression, which I can recall. One of, one of the things that’s so paralyzing about that is it’s so almost impossible to imagine that the world could ever be otherwise when you’re in the midst of it.

James (11m 59s):

Yeah. Whereas the gift of therapy, counseling, You know this kind of reckoning is that it also cracks open the presence so that you can start to imagine a different future.

Amy Julia (12m 11s):

Yeah. and that, I mean, that really speaks to the nature of hope, right? That there is some sense of being able to tether something in the present to a future promise. And, and even You know, I’m thinking of light in the darkness where it’s not, everything is Bright light right now. Actually everything is dark right now, but there is a light in the darkness and yeah. There’s something, there’s something to that. I’d love, actually, I wanna skip ahead in my own notes here based on what you just said, because something I found so compelling was when you were writing about nostalgia as a false view of history and progress as a false understanding of the future.

Amy Julia (12m 52s):

So I i maybe we can start there with just both of those kind of the problems with nostalgia and the idea of progress, but then also what’s a, what’s a proper, like, what’s a corrective in terms of how we think about the past and the future?

James (13m 7s):

Yeah. So one, one, let’s say feature of this kind of Spiritual Timekeeping is an awareness that to be human is to inevitably be the kind of creature who remembers and is indebted to a past and also a creature who lives leaning forward and is, and is in some way oriented to a future. Right? So we’re, we’re always stretched between these, but how we remember and how we live forwards is kind of what’s at issue. And yeah, nostalgia. I, I think nostalgia is such a powerful narcotic in our culture right now.

James (13m 48s):

And the problem with nostalgia is not that it remembers remembering is not that we’re enjoined to remember. I think it’s crucial to remember. Yeah. The problem with nostalgia is what it very actively forgets it. Nostalgia is always this highly edited version of the past. It’s this kind of romanticization of some history and usually someone’s history and some version of a history where some benefited and others didn’t. Yeah. Or even in my personal life, I can engage in a kind of Spiritual nostalgia where it’s like, well, I remember You know when I was 20 and going to college worship services and I was so close to God.

James (14m 33s):

Yeah. But you’re also forgetting like how immature and foolish you were. So you can, you can a again, you can romanticize the past. Yeah. I, I think that’s a problem with nostalgia. I think a kind of, sort of overconfident progressivism Yeah. Is a way of imagining a future which is also kind of disordered. Because what happens now is you, you project a future entirely confident in your own ingenuity and what you think you see right now. And I just, I, I, I’m a, I’m a devotee of St.

James (15m 15s):

Augustine. I think Anytime, we get overconfident in ourselves is usually a recipe for not, not just disappointment, but actually it’s gonna be dangerous for somebody because we think we see the way it’s supposed to go, and now we’re going to make it happen. And I think we should all get a little bit nervous about that. So, so the contrast then between, let’s say, what does healthy remembering look like? Healthy remembering is this reckoning we were talking about. It’s this, this sort of recalling and realizing the way that the i I am today is the product of a story and a history that I have undergone and to, and to realize that God has been with me in all of that, even if God has to pick up the, the fragments in order to make a mosaic in the future.

James (16m 7s):

But in the same way, I think hope as you, as you mentioned, I think hope is so different from optimism. Hope is so different from just confidence in progress. Because hope, hope is an expectation of the future that is not indexed to our ingenuity or our purity or our moral superiority. It’s completely dependent upon a God who can raise the dead. Mm. You, you, you’ve probably heard the Leslie Negan line, I am neither an optimist nor a pessimist. Jesus Christ is risen from the dead. And I think that gets at Yeah.

James (16m 46s):

Something that’s distinct about hope. Yes. And I do think it’s difficult to be hopeful without some sense of a transcendence that’s gifting us something that’s, that’s probably a different conversation. But I I I do think one of the reasons that our culture struggles with despair. Yeah. And I understand it, like I get it, but I, I think we are more prone to fall into despair when, well, when we get burned out on our misplaced confidence in progress, but also when we don’t really have a sense that there’s anyone outside of us to whom we could entrust ourselves.

James (17m 27s):

And I think this is another way in which if, if, if Christians wanted to be gifts to their neighbors, we could try to live out how and why it, it looks different to live hopefully, which is, which is a lot harder than it sounds, by the way.

Amy Julia (17m 46s):

Yeah. I read, I think this was, I, yes. I read an interview in Christianity today with Mike Kos and Bono recently, and they were, I don’t remember which one of them said it, I think it was Mike Ko who said to Bono that he realized that many of their u two’s songs, even though they are laments because they are laments, they’re messages of hope because they are not despair. They’re not saying, here’s how it is and it will never change. They’re saying, here’s how it is, and it should not be that way. And so we are crying out against it because we know that there is something You know that sense of kind of tethering our hope to a promised future that’s different.

Amy Julia (18m 31s):

and that was a really helpful distinction for me to recognize lament as an aspect of hope. And I think, again, that’s so different than optimism that’s so different than toxic positivity. We just have to have a good attitude or a good mindset naming what is wrong right now, recognizing what has led to that in our past. And yet instead of that making us be people of cynicism, despair, or rage, it can instead actually be a part of turning us into hopeful people towards the future. That to me seems actually like this. I don’t know, great redemptive arc. Yeah. That is kind of miraculous, I guess,

James (19m 13s):

By the way, I have never heard the phrase toxic positivity before. Oh. But oh my gosh, does that make sense of so many things that I loathe? It’s absolutely true. And, and I thi I’m, I’m in the middle of bono’s memoir surrender right now. And it’s, it’s absolutely marvelous, especially for like a, a white dude of a certain age, even

Amy Julia (19m 38s):

A white girl of a certain age. So I I, I just read it

James (19m 43s):

And, and I think that’s exactly right. The sense of it’s, it is lament is lament because it’s haunted by hope. And it’s, and it’s also why lament is not just protest. It is protest. Right. It’s a confrontation and it’s a confrontation with God that’s honest and, and, and un veneered. but it is, you’re coming to God, which is what makes it a posture of trust and faith and hope and love.

Amy Julia (20m 14s):

Yeah. Well, one other thing I wanna just kind of pick up from something you’ve already said and that you write about in the book as well, is this idea of the fragments and pieces ultimately coming together in a way that is a mark of God’s faithfulness and essentially of, of God being the Lord of time. Right. Like that we are not like we cannot be masters of time. And I do think idolatry of time is one of the things that can come alongside time management. And I am very much convicted regularly of my own participation in that. And I have to remind myself, God is the Lord of time and I am not. And so when I do that, I think one of the ways in which the biblical story, and particularly the story of Jesus helps me, is that sense of these scars that were your death.

Amy Julia (21m 9s):

I mean, the, the symbols of your death become the symbols you demonstrate. I mean, you say to your disciples, like, look at this. This is what identifies me as the risen Lord is my scars. And so that sense of that brutal past being swept up somehow, and you, and you get here by the You, know at the very end of the book, especially into a story that not only, I don’t know if makes sense is the right word for it, but that can be beautiful and particular and again, hopeful and true. Yeah. I just, that seems like an important part of all of this.

James (21m 45s):

No, absolutely. And I, and by the way, I think what you say about the particularity of all this is really, really important. In other words, the intimacy and specificity of God’s being with us to, to, to gather up each of our particular wounds. Yeah. To, to gather up and to, and to reckon with by grace the, the traumas that we’ve endured. And so that, so that grace and redemption are not just these reset buttons so that you sort of erase what’s gone before.

James (22m 27s):

And now I’m a new creation because I’m a blank slate, or I’m a You know I’m a new character in the video game. It, that’s not how God’s redemption works. And Christ, Christ exemplifies that God’s redemption is in. I think this is more miraculous, right? It’s not that we all start now as these generic Christians who, who have this new life. It’s no, it’s in fact me with all my particular hurts and harms and histories and gifts and talents and the history that I have lived through is part of what God gathers up now and sort of rereleases. It’s, it’s like a digitally remastered version of a U2 album.

James (23m 10s):

Right. So you, there’s, and, and so it comes with all of that specificity about it. And, and God is going to use what I have undergone as almost like a lever or a, a You know. It, it, it will be part of my mission in the world. Right. Because I have lived this particular history. This is why I, I think as You know, I emphasize discernment a lot as sort of You know, the pivot point between reckoning with our past and hoping for a different future is discerning, okay, what am I called to now? And, and listening for the spirit’s guidance in that regard is also being attuned to the particularities of my story.

James (23m 58s):

And to say, this is, this is what God has sort of brought me to. And this is what maybe only I could do in the world because only I have lived this history. I, I find it intimate and restorative in ways that other versions of redemption sort of, I think fall flat.

Amy Julia (24m 18s):

Yeah. Because I, I mean, again, back to that particularity, and I think we, we don’t wanna go in the direction of God doing the wounding, but in the direction of God being able to always overcome like to, to hold all of that. And I think this actually like leads me to some questions I have around the idea of regret. Because one of the things you write about is contingency and just that sense of knowing, I think you get to a certain point, again, we’re kind of admitting our middle-aged status here. Yes, I’m a little younger than you, but both of us have gotten to a point in our life when we can look back and say, oh, I didn’t even know I was closing the doors I was closing.

Amy Julia (25m 1s):

I didn’t even know I was making the choices I was making. But now here I am. And like there are possibilities that honestly, 10 or 20 years ago were still open to me and they aren’t anymore. And I certainly found myself in this period, I don’t know, maybe five years ago, in the last three to five years, where I felt a sense of deep regret over some of the choices that I had made. And I was again, really convicted and, and comforted too, I think by this idea that the, that God is the Lord of time. and that means the past, the present and the future. And So, If, even if I did make, I don’t know, bad choices along the way, that doesn’t mean that God was not present and cannot redeem that.

Amy Julia (25m 43s):

And some of those choices were necessary ones, even if they narrowed my life. Right. And so it feels less filled with endless possibilities. There still are particular possibilities ahead for me. And so I just thought I’d ask you to talk about the idea of contingency, but maybe also where, where regret and faithfulness fit into it. Yeah,

James (26m 5s):

Yeah. No, absolutely. I do think this is a, this is a feature of accepting our mortality and accepting our creature hood, which I just think middle age and later is sort of the season of your life that you get to a place where you can accept that in, in a way. I, I don’t want somebody in their twenties to imagine all the possibilities that have been shut down, do You know what I mean? Like, like be ambitious and dream and You know there are so many doors that’s that’s exactly what somebody in that season of a life should be doing. But I, I think, I think it’s worth saying too that it’s okay if we still sort of, I, I expect to actually in an ongoing way still have sort of twangs of, if only do You know what I mean?

James (26m 56s):

And, and that’s just a, that’s just confession, right? That’s just confession to say that might also be a natural part of being, like, in my experience, what I find is You know, I’m, I’m in my fifties now and I still feel like the world is, I’m still learning so much about the world. And so, and learning about like whole new kind of corners of the world. And then you, so then all of a sudden You know you’re, you’re 52 and you learn about this whole other sort of sphere of culture or something like that, and you’re like, I’m kind of mad. Nobody told me about this when I was like, if I had known this was yes, I think I would’ve done some things different. And then inevitably, Deanna, my wife will be like, but, but here’s your story, right?

James (27m 38s):

And here’s, here are all the gifts that have been handed down to you. And the question now is what are you going to, how are you gonna pick those up gratefully in such a way that you accept limitation? I mean, I I I really do think to remember the distinction between creature and creator Yeah. Is to sort of accept our finitude, to accept our mortality, to live with our limitations and to then realize still how much is possible within those limitations. Right? Yeah. It doesn’t mean my future just looks like my past. It just means, okay, it can be liberating to know these are my, this is my repertoire.

James (28m 24s):

This is, this is where, this is my corner of the field to till, and now let’s dig deep, let’s You know go long, and to be faithful along obedience in, in one direction. I think as Eugene Peterson quoting Nietzche, I think that can be liberating because then I’m not constantly, I don’t have sort of fomo, vocational fomo about like, oh, if I could have done this, if I could have done this, that’s also exhausting and paralyzing. Right? And so I think there’s gifts to be found in the accept.

Amy Julia (28m 59s):

Do You know the novel, the Midnight Library?

James (29m 2s):

I don’t.

Amy Julia (29m 3s):

So it, I mean, you might have fun with it. You could read it in like two days. Yeah. It, my son weirdly was assigned to read it in eighth grade as kind of a bonus reading thing. And he gave it to me, and it’s a woman in her, I think she’s actually in her mid thirties who tries to take her life and swallows a lot of pills. And it’s then she kind of enters into this mis it’s kind, I mean, it’s not really sci-fi, it’s like, anyway, she ends up in this library where she’s in a liminal space between death and life, and she gets the opportunity to live all the lives that she wishes she had lived. And so, and Anne, if she finds one that she actually would like to, to stay in, she gets to.

Amy Julia (29m 43s):

So it’s kind of a metaverse thing happening. You know, interesting. but it’s really a meditation, I think, on these themes of regret and of wait, what would it mean to actually receive the life that I have been given, the mistakes that I have made? And there’s no God in this book. But I don’t know, I found it so compelling from, in thinking through, from just a very You know fictionalized Yeah. Place all of these types of questions and really saying, what if I am supposed to be living the life I’m living? And, and all of the messiness of it and the giftedness of it is actually making me even today who I am.

Amy Julia (30m 25s):

And, and I really, I really enjoyed it. And I

James (30m 27s):

Yeah. No, that’s great. No, that’s a, that is a great setup for exactly what we’re talking about. Yeah. And, and I know in, in, when I am sort of in my spiritually healthiest place, which is not always, I know that this is bound up with gratitude, so it’s mostly I I, and I don’t know what’s the chicken and what’s the egg in this regard. Yeah. I don’t know if cultivating gratitude is what helps me come to these places of acceptance and focus or if it’s working on the acceptance and focus. And then when I have that posture, I realize, oh my gosh, I can’t believe this is my life. You know. Right. I, I think content

Amy Julia (31m 9s):

Well and ah, all right. Two directions I wanna go. One is in talk to talk about the present moment, cuz we’ve talked a lot about like what we need to do to understand the past and the future. And then there is this question of what it means to live Faithfully in the present. And I wanna link that to some of the ways that I have learned a lot and grown a lot in these areas is by having a daughter with Down syndrome. So this, and it’s not to say, I mean, penny absolutely thinks about the future and remembers the past, but she also has a different relationship to time than I do. There’s an abstraction to the future in the past that is truly hard for her intellectually to understand.

Amy Julia (31m 51s):

And I do think that actually enables her to live more Faithfully in the present than I do a lot of the time. So that’s something that she offers to me and invites me into. And having her in my life has helped me just think a little more differently about people who, who have dementia for example, and who are much more fully in the present than I am. And, and the ways that can obviously be a problem in and of itself to only live in the present, but it also how it can be a gift. So I’m curious, like, just to hear some of your thoughts on what it means to live Faithfully in the present in time before God,

James (32m 27s):

I feel like I should be listening to you here because I, I mean that I, I think that that strikes me as really a powerful way in, in a sense you’ve experienced the discipline of a way of attending to time that has, has maybe because I, I think mostly what living Faithfully in the present looks like, maybe not mostly significantly, is a mode of learning what to let go of. Yeah. Right. It, it’s all, it’s almost like there’s a sense in which to live Faithfully in any now is always suffused with a certain Sabbath like quality.

James (33m 10s):

In this sense, I think the, the, the, the heart of Sabbath is learning that we’re not in control. Yeah. And so the reason why you can take a day off is precisely cuz You know the world doesn’t depend on you. Right. And, and you can let it go. And I, I think that’s really an intensification of what living Faithfully in the now always looks like. It always has this tenor of an openhandedness a kind of a kind of attention to what is given. where you realize I’m never gonna master everything.

James (33m 52s):

I’m never going to accomplish everything and I’m not in control, thank God, therefore, alright, what am I released to attend to right now? Yeah. Does that make sense? I mean, how does that play out in your experience?

Amy Julia (34m 4s):

No, that really, I I I really, I think that idea of being released to attend, especially knowing that our attention is so fragmented as humans, but also as particular humans in our moment, there’s so much distraction, which like absolutely on the one hand keeps us kind of on the surface of the present moment, but it also distracts us from the present moment. Yes. Right. And from attending really to the work of love, which is what we’re called to I think all the time. And Yes. And yet when our attention gets Yeah. Turned to the wrong things, then that love gets distorted.

James (34m 39s):

The the the tyranny of the urgent Yeah. Is so different than being present to the present. Right. And I think you’re right that we, we, we do need to just name and recognize that there are so many kind of cultural forces and cultural liturgies I would say that, that are really trying to mitigate against our capacity to be present to the present and instead are just trying to sort of honestly purchase our attention incessantly so that we’re never really fully present. We’re just scattered, distracted. And I, I think, I mean there’s a, there’s a weird sense in which, cuz you, you said it too, that that what we don’t mean, it’s not like follow your bliss, do You know it’s not, it’s not unthinking given over to hedonism or something like that.

James (35m 31s):

There’s, we have responsibilities that that and covenants and promises we make that transcend the now. But there there’s another sense in which I think my being faithful in the present is probably always a little microcosmic call within the season of a life. And so this is another theme that I talk about a bit in the book, which is I find it liberating and helpful to imagine that I don’t just experience time as a chronological sequence of TikTok or talks for that matter, but I, I experience it as You know.

James (36m 15s):

It kind of congeals into chunks of a life that we might think of as seasons. And and depending on the season in which you might find yourself, you’re sort of default attention in the present could be a little bit different. Right. Like it could be, it could mean that you’re just sort of primed to give yourself over to a kind of attention because you’re in this season of your life as opposed to another season. So You know the, the college student versus the young parent versus the the aged partner who’s caring for a spouse with dementia.

James (36m 56s):

I mean, those are just such radically different seasons of a life and the kind of way that I’ll be faithful in the now will be different because of the season in which I find myself.

Amy Julia (37m 6s):

Well, and what you’re talking about makes me think about a couple different things. And again, back to kind of the individual and the collective. Yeah. So on the individual level, I’m thinking about, I was interested cuz you wrote about time as being either neither linear nor cyclical, or both linear and cyclical. Right? Like that we tend to think of it in these terms that might not actually work if we think about a timeline. But if we think about a cycle that always repeats back to the same place, that also is not even what we’re talking about. Right. And, and I’ve been writing a lot about healing as a spiral where there’s a sense of great, you’re coming back to the same place and yet you’re actually, and I think by the grace of God might be spiraling upward.

Amy Julia (37m 54s):

Right? So it’s like, oh my gosh, we’re having the same fight again, and yet it’s actually different because I’m aware of whatever it is, You know, even the awareness that it feels the same. Right. And so I thought when I was reading, I was like at that, that sense of seasons, which again, I’m coming You know even just the winter, fall, spring, summer, right. Like I’m, yeah, there’s a place of return and yet there’s also differences in the land and in the air and in the climate You know all of these things. And I do think that as an individual to recognize, as you said, to discern the season, to recognize the limitations inherent within that, to not see those as necessarily permanent.

Amy Julia (38m 38s):

and that can be a hopeful posture. But then I’m, the other thing I’m thinking about this is also early in the book you write about knowing when we are and not just knowing where we are. And specifically one of the examples you’d give is the Black Lives Matter debate and why the historical moment really when we are comes to bear so much on whether or not we say Black, Lives Matter. Could you just speak to that a little bit? Because that again, I think is kind of that collective knowing what season we’re in really matters.

James (39m 9s):

Right, right. And and this is where I, I do think that there are different kinds of theologies honestly, or spirituality that, that really are just don’t take history seriously. Yeah. So they think You know time is flat because all we care about is eternity. And so therefore they’re not really primed to read and appreciate the textures and specificity of histories that we are, we have lived through and that we are living in. And so, so when You know in, in, in the face of, again, just systemic police brutality against black people in the United States, when when people started saying as a protest that Black Lives Matter, you kind of heard, and and I think sadly it came mostly from Christians, it seemed to me who said, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa.

James (40m 1s):

Wait, wait, wait, wait, wait. All lives matter. All lives matter. Which I didn’t hear them saying that before people started saying Black, Lives Matter. Right. So that’s, that in itself is interesting. And so what I, what I think is that’s another example where, oh, we retreat to this kind of generic pseudo eternity and don’t realize that in a sense, to say that all lives matter in this moment, in this place at this time, given the history that we have lived through is really false. I mean, you could say it’s kind of like theoretically and, and right. Universally true. But, but to say it now, given our history and given this moment is really false witness, I would say.

James (40m 50s):

So we have to take our histories seriously. And and this is where I, I do think Americans maybe broadly, but I also think Christians in a particular kind of way, were not comfortable facing the specificity of the histories that have been handed down to us. and that to me, that’s an example of our blinders. That’s an example of our, like we don’t wanna face and, and we have illusions that we aren’t heirs and inheritors of sort of accumulated ways of being that have been handed down to us, which I didn’t choose to inherit, but I’ve benefited from do You know what I mean?

James (41m 36s):

I, I’m a I’m a a white man who gets to move in the world in a particular way because the world has been constructed in certain ways to benefit me. Yeah. And in that sense, the world didn’t have to be that way. Right. And by the way, the world is not going to be that way in the kingdom of God. Right. So I think facing the specificity and particularity of our history is a huge part of it. I mean, when, when you were talking earlier too about You know cyclical versus linear, I think your notion of the spiral is exactly right. In fact, there’s a, there’s a 19th century Danish philosopher, not that your listeners care about this, but kard.

James (42m 17s):

So in kard that’s, he has a whole book called Repetition, which is exactly about that way in which we experience time as this sort of, it is a, a return, but it’s always a return forward. And I think about that a lot in connection with the liturgical calendar and the church calendar where You know every year we go through advent and Christmastime and epiphany and Lent and Easter, and you kind of keep living the life of Jesus over and over and over again. So it’s, it’s cycle like. But on the other hand, we and I are different every single time we relive it.

James (42m 58s):

And so we are hearing and attuned and attentive and maybe broke open in new ways that now finally some aspect of God’s grace and redemption sort of makes its way into us. And so we need the repetition to actually keep inhabiting the story.

Amy Julia (43m 17s):

Amen. Yeah. I am astonished. Especially for me, the advent season is a time of every year I’m like, really? There is more to know, there’s more to understand, there’s more to receive. Are you kidding me? Because it’s such a rich time of, again, returning to a pretty simple story and one I’ve known for a real long time. And yet yeah. Just being able to receive more,

James (43m 44s):

Always some other, the always the profundity of such simplicity. Hmm. It means that you, you could literally spend an eternity dwelling in that mystery and confronting new aspects and seeing how it intersects with your own life and your own story and where you are now when you are now. Yeah. And so I, that’s why I think it’s a gift.

Amy Julia (44m 5s):

Hmm. I I absolutely agree. Well, I have one final question that goes back a little bit to the kind of Spiritual Timekeeping time management side of things. But I know you’re someone who’s written a lot both in this book, but elsewhere about habits, about liturgies, about the ways in which how we move through the world, shapes what we believe, who we become. And I’m curious about any practices that you have found that actually help you be someone who is a Spiritual timekeeper Yeah. And not a person You know trying to urgently respond to the distraction of the moment.

James (44m 41s):

Right. I, I will say I do, we were just talking about the liturgical calendar. I think letting the, the liturgical calendar sort of frame how you spend your days is, for me is a real sort of, kind of guardrail that channels you into a certain way of attention that also kind of pushes back on other default modes of Timekeeping in our culture, consumer calendar, the academic calendar, whatever it might be. Yeah. So I, I do think that that’s kind of a big macro influence for me on a micro level. Yeah. It’s a, it’s a good question. I should have a better answer to it, except that I, I think it’s probably just the Rhythms of my marriage.

James (45m 27s):

Hmm. But I have to say there that we You know, we’re kind of like still feel relatively new empty nesters. And so I think Deanna and I, I, I, let me put it this way. I have Rhythms that are not just dependent on my choices and my decisions. They are sort of givens in our life that we take as the framework that we are living in. And so You know the way we started mourning the way we close a day, the way we sort of spend time together doing things that we could do more efficiently apart, but nonetheless we commit to that time together. There’s, there’s something about, I think we’ve signed up to waste time in a good way because we’ve refused efficiency Yeah.

James (46m 16s):

As the, as the overarching good. It, it’s not a great answer to your question, but I, I think I should, I should think about that more carefully.

Amy Julia (46m 24s):

Well, I think it’s good to, I mean, again, I agree with you on the liturgical year and even your comments about like the, the quote unquote wasting time. I think about, again, back to our daughter Penny. I wrote a piece for plow I think a year ago about an experience I had with her where we were in a national park and the rest of the family was just gonna move more quickly. And so we, I said, go ahead, I’ll stay back with Penn. And we were still hiking through a beautiful forest, but we, it was one of those things where the way I almost expected the narrative of that day to go was that because we walked slowly, we saw more beautiful things, and the others You know ran ahead kind of the, what is it, the rabbit in the tortoise or whatever.

Amy Julia (47m 8s):

Yes, yes. You know, like in the race. Right. And the bottom line was like the rest of the family saw the more spectacular views. And we didn’t, but I also realized that what I received that day was my daughter. Like I got her, I got love, I got presents. And not that the rest of the family didn’t, it wasn’t and either or, but, but there was was this sense of, my expectation is if I quote unquote waste time, I’m gonna be given more of it some. And it’s like, no, no, no. Like it is that, in that being present to someone else Yes. and that to everyone else, again, there are limits on that and you still got work to do. And, and that’s fine. Yes. But whether that’s a weekly date night or as you said, slowing down in the morning or the evening to just listen and attend to one another, or I think the practice of Sabbath is another Spiritual Timekeeping practice.

Amy Julia (47m 57s):

Right. And then the liturgical year, I mean, I think that gives people plenty to go on.

James (48m 1s):

Yes. I I’m so glad you, you highlight That’s a, that’s a wonderful reminder too that when we’re talking about wasting time, Marva Marva Dawn wrote a book on worship called A Royal Waste of Time, which I, I think is really, really brilliant. We’re talking about wasting time relative to what a cult of efficiency tells you. Yes. And we’re always talking about quote unquote wasting time with others. Yeah. I think it has to be. Yeah. And, and in that sense, I guess I think the other thing that we have in our lives are sort of Rhythms of friendship keeping that are their own modes of Spiritual Timekeeping like we have with our, our dearest friends.

James (48m 47s):

We have You know, I think now a 17 year tradition of Wednesday night wine. Wow. Right. And that’s just sort of like, that’s just a, an appointment.

Amy Julia (48m 56s):

That’s the

James (48m 56s):

Main thing that we keep. And, and there are times when that has been a table in the wilderness You know it’s been, but it is, I, I think the more we imagine our Timekeeping tethered to friendship tending, the more we will sort of learn How to Inhabit Time faith.

Amy Julia (49m 18s):

Mm. I love that. That’s a perfect place to end our conversation too. So thank you so much for your time today and for your wisdom.

James (49m 27s):

Thanks for your thoughtful questions. I really enjoyed it. Thanks so much.

Amy Julia (49m 32s):

Thanks as always, for listening to this episode of Love is Stronger Than Fear. And I would love to hear from you at the end of this year, as we’re looking ahead to 2023, what are some of the questions or thoughts that this conversation prompted for you? Are there other people you would love to hear on this podcast in the future? Let me know. My email is Amy Julia Becker writer gmail.com. I always wanna give thanks also to Jake Hanson for editing this podcast to Amber Beery, my social media coordinator. And I also always want to end with a sense of blessing and prayer. A prayer and a hope that as you go into your day to day, you’ll carry with you the peace that comes from believing that love is stronger than fear.

Learn more with Amy Julia:

- To Be Made Well: An Invitation to Wholeness, Healing, and Hope

- S5 E22 | Disability and the Speed of Love with Dr. John Swinton

- S6 E5 | The Healing Work of Rest with Ruth Haley Barton

If you haven’t already, you can subscribe to receive regular updates and news. You can also follow me on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Pinterest, YouTube, and Goodreads, and you can subscribe to my Love Is Stronger Than Fear podcast on your favorite podcast platforms.