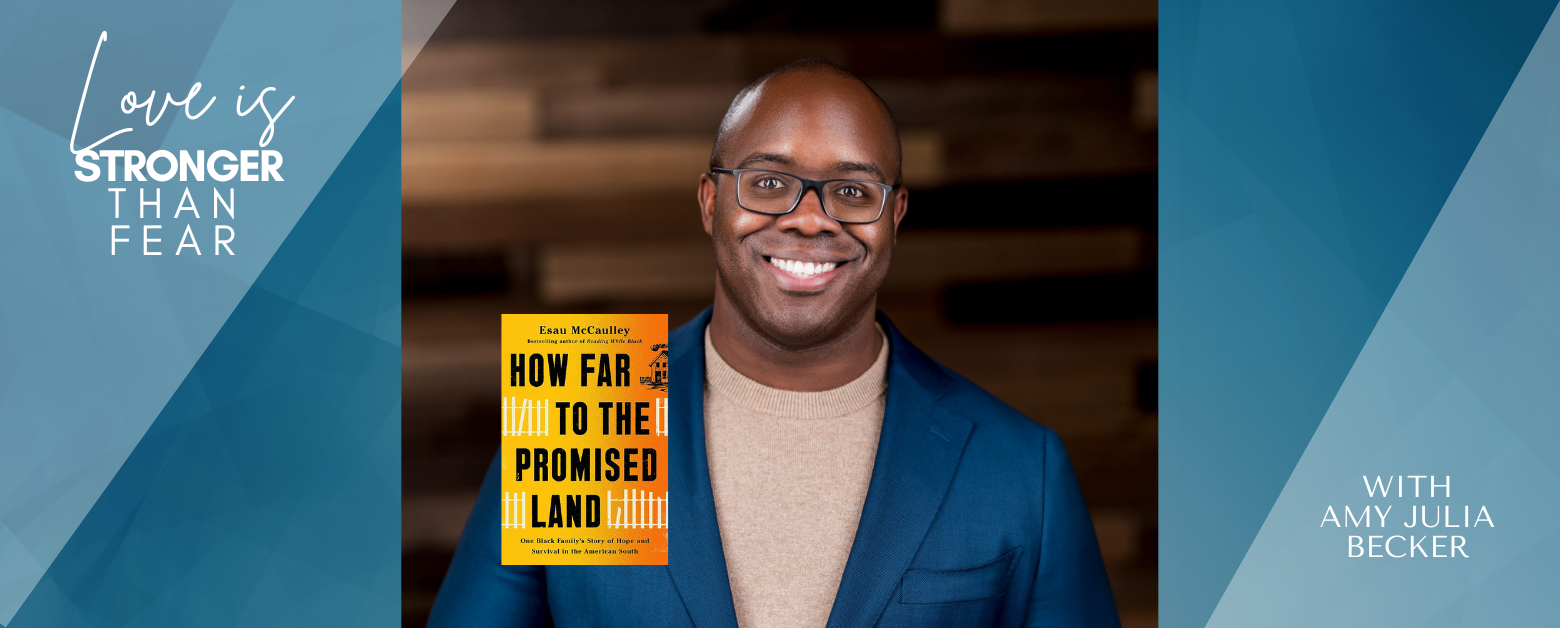

“Whose stories matter?” Esau McCaulley, author of How Far to the Promised Land, joins Amy Julia Becker for an honest, hopeful conversation about:

- being Black in America

- honoring the messiness and complexity of our humanity

- holding on to hope in the goodness of God

Guest Bio:

“Rev. Esau McCaulley, PhD is an author and associate professor of New Testament at Wheaton College. His writing and speaking focus on New Testament theology, African American Biblical interpretation, and Christian public theology. His new memoir How far to the Promised Land, questions the narrative of exceptionalism that he, and other Black survivors, are conditioned to give when they “make it” in America. His book Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope won numerous awards, including Christianity Today’s book of the year. Esau is a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times. His writings have also appeared in places such as The Atlantic, Washington Post, and Christianity Today.”

Connect Online:

- Website: esaumccaulley.com

- Instagram: @esaumccaulley

- Facebook: @OfficialEsauMcCaulley

- Twitter: @esaumccaulley

On the Podcast:

Season 7 of the Love Is Stronger Than Fear podcast connects to themes in my latest book, To Be Made Well, which you can order here! Learn more about my writing and speaking at amyjuliabecker.com.

*A transcript of this episode will be available within one business day on my website, and a video with closed captions will be available on my YouTube Channel.

Note: This transcript is autogenerated using speech recognition software and does contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Amy Julia (7s):

Hi friends, I’m Amy Julia Becker and this is Love. is Stronger Than Fear. We are back for a new season. I’m really excited to share lots of conversations with you and I’m particularly excited about getting to start with my guest today, Esau McCaulley. I would like to gush for a moment about him and about his new book, and let me tell you this title. Okay? How Far to The Promised Land One Black Family’s Story of Hope and Survival in the American South? So this is one of those books that I started out reading in my Read it for the Podcast pile and it moved very quickly to my read it before going to Bed Pile because I just liked it that much.

Amy Julia (51s):

I just wanted to keep reading. So that’s pretty much the highest praise that I can give a book, especially a book by a scholar. Dr. McCaulley is an associate professor of the New Testament at Wheaton College. He’s the author of the critically acclaimed bestseller Reading While Black. He writes regularly for the New York Times and he’s also just a great conversation partner and an academic who is able to translate big ideas into very accessible stories. So this is a conversation about being black in America about honoring the messiness and complexity of our humanity and about holding on to hope in the goodness of God.

Amy Julia (1m 32s):

I am thrilled to be sitting here with my friend Esau McCaulley. Esau, thank you for joining us today.

Esau (1m 38s):

Thank you for having me. I’ve been on, this is my second time,

Amy Julia (1m 41s):

This is your second time. So I feel very honored whenever I have a repeat guest listeners to the Podcast might remember, but also could just go back, you wrote a book a couple years ago that was a bestselling account of really a scholarly account of reading the Bible. It’s called Reading while Blacks, right? Yeah. Am I getting the title right? Yes. Yeah. So, and in some And there are hints in that book that you might head in this direction of where you ended up, which is more of a memoir called How Far to the Promised Land, which, oh, there hint,

Esau (2m 15s):

We’re talking, I didn’t know that There’s hints.

Amy Julia (2m 18s):

Yeah, you have a tone in reading while Black of just, you’re able to tell personal stories even in the midst of that’s a more scholarly book, but there’s still an accessibility to it and an ability to recognize that we don’t come to faith and we don’t come to the Bible just from this like kind of clinical academic objective perspective, but also with our personal stories. So it didn’t don don’t know, it didn’t feel terribly surprising to me that you would end up here, but maybe, maybe I’m alone in that. don don’t know. No,

Esau (2m 51s):

No, no. I mean, I’m glad I didn’t know if people would go, what’s this new Testament scholar trying to do some kind of memoir, tradey kind of book. So I’m glad that there was some hints of different things that were in me and so I’m glad that you saw it there.

Amy Julia (3m 8s):

Well, and I’ve also followed your work because you’ve written don Don’t Know pretty regularly for the New York Times. And again, in that context, I feel like you are taking personal stories and using your training as a scholar to help me understand the church in America being black in America, these kind of bigger, almost sociological things that are happening. And I see a lot of that in this book as well. So I think you, you weave it all together and it, it all makes sense, at least from my vantage point.

Esau (3m 43s):

Yeah. So there is kind of like two to, I mean when reading Why Black came out, it was obviously a little bit more on the academic, but it kind of balanced academic and more trade stuff. And since then I’ve done some things that are a little bit more accessible. I wrote a children’s book, Josey Johnson, the Holy Spirit. I wrote a book about Lent and obviously I’ve done basically a, a little over once or twice a month is what I write for the New York Times. So obviously those pieces are much more in a, an accessible voice. And so this book is actually more in the New York Times voice than it is some of my more technical scholarship.

Amy Julia (4m 20s):

Yes. And I, I wanna agree that you have made that your story a very accessible one, but it’s also one where it’s not surprising to find out that you have academic training just because it’s so deeply thoughtful. And I, I will start though by asking you, there’s a really early on you share an anecdote And, you write, I learned early on to tell the story America requires from its black survivors. And then you go on to essentially say, but I’m not gonna tell you that story. Right? So I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about the story that America requires from its black survivors, but also the story that you want to tell instead.

Esau (5m 2s):

Yeah, I call it, and my, my, my editor would not let me use this as quip. They took it out. So I’m gonna slide it in right now. I call it a Horatio Alga story. And so what that mean is that we love to hear the story of people who grew up in poverty who overcame tremendous odds to make it to the middle class like the Promised land. And there’s something about telling that story that does a lot of things for the reader. So it allows you to kind of condemn the racism and the poverty ’cause you, you’re rooting for the protagonist. Like, oh, they should experience those things. And so you kind of go on the emotional journey with the protagonist, but You know they’re gonna live because they wrote the book, right?

Esau (5m 44s):

And so the danger that you yes feel isn’t actually real. And when you get to the end, those books can can not all of them, they can say, well look, if you work really hard you’ll make it. And so yes, America treats black people poorly, but some of us make it. And if enough of us make it, then America is can’t be so bad. You gotta see this thing all the time. Look at this successful black person, how can America have problems? And what I wanted to say is first of all, those stories can normalize the req, the requirement for exceptionalism, like real progress and just being able to survive as a normal person without climbing through all the things people to climb through. But the second thing is it has a wrong definition of success.

Esau (6m 27s):

And, there are tons of people who were in my life who did not become successful as society defines success, but their lives matter too. And attending to their stories yeah, teaches us something about America as well. And so it’s not just that I want to question the exceptionalism narrative, that’s part of it, but it’s like, well Whose stories matter and what, and what tends to happen is people who the exceptional person passes along the way are simply object lessons that teaches the hero things they need to know for their journey. I wanna say no, no, no. It isn’t just what this person taught me that matters. Their life in and of itself is beautiful and important and it teaches us something about what it means to be human, even if they don’t make it all the way to the Promised land.

Esau (7m 14s):

And so it’s, it’s really a way of saying if you’re gonna tell a story, the hero isn’t the only person who matters. It’s the people who are around these, around someone who makes them who we are. We’re all shaped by community. And so when it came time for me to write a memoir, the only thing that felt true to me was not to tell my story, but to tell the story of my community, my church, my family, my neighborhood, my city the South as a way of getting at the truth of things.

Amy Julia (7m 51s):

Yeah. And I really appreciated that you directly addressed that very immediately within the book because there is a tendency, I was actually, I was just having a conversation with a faculty member at the school where my husband works, a black faculty member about kind of school teacher hero narratives, movies like Stand By Me and oh there’s one with Michelle Pfeiffer. So we were talking about that and how tempting it is for both of us. He’s like, don don’t know, he’s probably a 30 year old black man and I’m a 46 year old white woman. We both get hooked by those stories and yet they perpetuate a narrative both of like in those, in the Michelle Pfeiffer case like white saviorism.

Amy Julia (8m 35s):

But in either case of just like exceptional heroes as opposed to both what you’re saying like community support in terms of what matters and also that sense of like it’s who we are that matters. And if we are gonna hang our hopes on individuals overcoming against ridiculous odds, that should never be ridiculous in the first place. I mean, You know you just do a really good job of gently but firmly knocking down I think some of those expectations as a reader that I am just going to kind of celebrate with you as you leave behind all of the You know. ’cause you also do a good job of every aspect, every aspect of your story is complicated in what I would say is a good way.

Amy Julia (9m 22s):

Like in a way that’s where you say we’re not having heroes and villains here, You know whether that’s like a dad who is kind of haunts you in some ways throughout the book and also You know You are able to really reckon with what’s going on with my dad who was not the dad I wanted him to be. And yet also how can I understand that and honor him as a human there. And there’s so many, he’s probably the most prominent character in that role. Yes. But there, there, there’re plenty of them. And I thought I might ask you a question that maybe we’ll get at that a little bit. One of the things that fascinated me throughout the book as I was reading was your name.

Amy Julia (10m 2s):

So we learn as readers that you are, your name is Esau Daniel McCaulley Jr. Are you junior?

Esau (10m 9s):

Well that’s a question, isn’t it? Could

Amy Julia (10m 11s):

You tell us the story of

Esau (10m 12s):

Your,

Amy Julia (10m 12s):

Could you tell us the story of your name? Yeah, tell us about your name.

Esau (10m 17s):

It’s really interesting because that is a story that I have been sitting on for most. I mean, I’ve known them my whole life, but I’ve not told people this story anywhere in print. And most of the time if you meet me, I don’t tell you their story. So people oftentimes ask me, how did you get your name Esau? This is like a question that like I get, it’s like the sec, if you, if You know the Bible, the first question you ask is like, why are you named Esau not Jacob Or, or what happens when people meet me? They, they, when they meet me again, they always change my name to a slightly more acceptable Biblical Cal character. So like, Hey Eli or Elijah or You know, they kind of go Enoch, it’s gotta be somebody better than Esau, right?

Esau (11m 0s):

And and I kind of go, Nope, it’s Esau and I in the story. I mean it’s kind of hard to will

Amy Julia (11m 8s):

You just for any

Esau (11m 10s):

Yeah,

Amy Julia (11m 11s):

For people who don’t, will you just tell for any listener who doesn’t know? Like if people don’t know Esau from the Bible, will you just tell what that story is?

Esau (11m 18s):

So there’s two brothers in the Bible, Esau and Jacob. Jacob is the chosen brother who becomes the founder of the nation of Israel. Like from Jacob comes the 12 traps. And so Jacob is the chosen one and Esau is the, is the Unchosen one. And Jacob steals Esau’s birthright. So Esau is the older of the two twins. He’s supposed to inherit all of his father’s stuff, but Jacob kind of steals it from him. And so Esau is kind of this myth fit character who can never really get himself together throughout most of the Biblical narrative. And he becomes the founder of this group of people call the, the mites who are Israel’s kind of arch enemies as the story goes along.

Esau (12m 2s):

And so in the story then everyone names their kid Jacob. There’s tons of Jacobs all running around because Jacob is the chosen one. Esau’s like the Unchosen one. It’d be almost not equivalent to but like this name your kid Judas. It just doesn’t happen very often. Right? And so how did I get my, how did I get my name? No shade of the Judases out there, but I’ve never met another Esau in person except for my father who shares my name. To make a long story short, I’ll tell the first part of the story. They gotta read the book to get the whole of the narrative. But my, my father, my father’s father was illiterate, but he was a pastor.

Esau (12m 42s):

He was a minister at the time. And so he opens the Bible and he points at a word to pick a name for his son. And he, according to the family lore, he opens the Bible and points to the name and the name that he points to is Esau. So he gives his father, he gives his son the name Esau. And then, so my father’s name is Esau McCaulley. So my father wants his firstborn son to be named Esau as well. But my mom’s also the child of a pastor And. she knows that Esau’s kind of a, a misfit in the Bible. So she says, well we need to give him a better Biblical name to balance it out. So she gives me Daniel as a middle name and Daniel’s this heroic character who it’s faithful to Israel under exile.

Esau (13m 25s):

So, so I’ve become Esau Daniel McCaulley. And so my father for most of my life is Esau McCaulley and I’m Esau Daniel McCaulley. And that changes later on in our life. But that idea of, for a long time I used to have this fear ’cause Esau at this key moment in his life makes a a bad decision. He trades his birthright for a pot of stew. And I used to always think that one day I’m gonna make some huge mistake like my namesake that kind of ruins ruins my future. And along the story at the end of the book, me and my father finally have a conversation about my name and the name that we share and its meaning and it’s a really important part of the book.

Esau (14m 11s):

And so I don’t wanna spoil it for people. It’s kind of weird to say like, you should read that part. But that’s one of my favorite parts in the book. And as a matter of fact, no, but I

Amy Julia (14m 18s):

Agree

Esau (14m 19s):

That’s, that’s one of the last parts that I wrote. I edited, I, I wrote, I I sent that in as a part of the last edits. So that’s the, that was the like I gotta have this in there and I put it in at the last minute.

Amy Julia (14m 34s):

Well I’m glad you incorporated it because it was, it’s a complicated thing for any of us I think, to share names with our parents. And that’s a complicated thing for you, which you also write about in the book then it’s complicated by this sense of nobody else’s named Esau because no one would want to be because of the story in the Bible. And then I will, I’ll give a little bit of a teaser for re for listeners to go by the book that the way you do resolve all of that doesn’t let go of that complicated history, but it is really a redemptive reading of your own life and of your relationship with your dad and of, and of Esau in the Bible.

Esau (15m 16s):

Yeah, one of the, one of the interesting things about it, my public life versus my private life is that most of my family, like my growing up, they all call me Daniel because that was how they knew me and my father was Esau. But just because of I was scared You know they ask you your name at school And, you just kind of shout out, they just use your first name And you, you’re afraid to correct them. So it’s really, it’s been really interesting that most people who’ve known me since I’ve been an adult call me Esau when all of my family calls me Daniel. And so wrestling with, because my father, as you’ll find out in the book my father leaves, when we our children, we kind of left to our own devices.

Esau (15m 59s):

And so Esau is kind of seen as the bad name and Daniel is seen as the good name. And so being even as an adult, for everyone to know me by the name Esau has always been a little bit complicated for me for a variety of reasons. And so people ask me a lot, which I get, like I said, tell me the story of your name. Often say, well you didn’t know me well enough to know the story of my name. And that sounds like it’s arrogant, but it was just like I couldn’t process really quickly all of that stuff. And so in the book I finally feel like I make peace with the name, which seems like a strange thing for everyone to be like, everyone seems like I’m just, I’m who I am.

Esau (16m 39s):

But. for me that name and carrying that name was complicated. And, and I’ll tell you, it’s interesting that you said that I don Dunno if you said it during this recording before that, that you kind of saw the future of this book in reading while black here’s something I would tell you that I think is, is a sneaky bit. So if you, once you, you’ve read it and you’ll understand how complicated my, the ne my relationship with my father was. He leaves when we are young and we are not really, we don’t have a relationship until the last few years of his life before he passes away. But reading Why Black is actually dedicated to my father. And so when people saw that dedication, it says this book is dedicated to the memory of Esau, Daniel McCaulley Sr, whatever else you’ve made me, I am your son.

Esau (17m 26s):

And so everybody was was saying, oh this is so sweet. You must have had a great dad and things are great. But I was actually my way of beginning to process the, the influence he had on me both like by his own absence. It was my way of saying, dad, I forgive you. And so how far to the Promised land, which is probably a weird thing to say, could be seen as a very long explanation of the dedication and reading why black in the sense of how do the people who we love, who hurt us shape the kind of people we become And, how do we make peace with that? It’s something I think a lot of people Yeah.

Esau (18m 8s):

Might struggle with. And so there was a sense, which I didn’t know it at the time, but I began writing this book when I pinned the dedication of reading Why Black after the book was finished and I dedicated it to him.

Amy Julia (18m 23s):

I love that story and though I think it leads into one of my other questions, which again is kind of a through line throughout the book that yes, this is a memoir and it’s a memoir about your family and it’s a memoir being black in America, but it’s also a spiritual memoir and all of those, those three elements, family and blackness and your story, but also the spirituality are somewhat embedded within the story of your name. Right. And so I’m curious about the faith aspect of that. Like could you just speak to not just growing up within the church, but like what does it mean? I know there’s a point in the book where you kind of surprised yourself by being asked who you are And, you say, I am a Christian.

Amy Julia (19m 8s):

And just what did it take for you to get to the point of like claiming Christianity as identity of Christianity becoming like a major orienting force in who you are? Yeah,

Esau (19m 22s):

Thank you so much because you did a good, you you get a gold star Amy as someone who read the book. Well oh, look at that and understood what was going on. Yeah. So a lot of times people want a, they, they want you to summarize your story and say tell me what this book is about in a soundbite. But our lives aren’t soundbites. We’re a bunch of things. And part of what it meant for me to grow up is to figure out what it meant to be black and cr black in America. But another part for me was to deal with the fact that my father left me, left our family when I was young and had a definitive impact on who I was. But those two, and we didn’t have a lot of money so we were poor.

Esau (20m 4s):

So I was black, I was abandoned by my father and I was poor. But the question that I was asking in the midst of all of that yeah, is where is God in this question? And so one of the things that I really respected is they allowed this book to be as Christian as I wanted to be, where that was relevant and not Christian at all in other parts. And what I mean by that is not the guy was absent, it’s just that like at every moment of my life I wasn’t processing things theologically. And a lot of times you just kind of lived And. you kind of live And, you kind of live, and of course God is there through all of it, but you’re not processing it through theological lens. But then you come to these places in your life when you say, no, no, no, the last five to seven years that have happened to me, where has God been?

Esau (20m 52s):

And so the freedom to tell an authentic story that weaves in all of them and and and ultimately And, you can put it this way, there’s two characters who aren’t on every page but who are on every page are both God and my father. And their absence is a presence in places. And so the the freedom to tell that kind of story where a significant sense of making sense, a significant part of making sense of who I was, was figuring out the God question. And I know there’s a lot of books to talk about how you found your way to God. There’s tons of books like that and there’s tons of books about being black in America.

Esau (21m 34s):

There’s tons of books about poverty, there are tons of books about dealing with like parental abandonment. But all of those things that want a stor something I wanted the freedom to tell. And I’m really proud. There’s something that excite me, that excites me about this book that makes me, that makes me proud to have written it. It is, hmm, I think that the, the spiritual part of the book that is crucial to my, to to, to who I am comes through and it’s, it’s, it’s how and and, and, and maybe I wanna put it this way. I didn’t wanna do something simple as how did I make it through?

Esau (22m 15s):

I made it through because of God. I mean it’s way of saying it, right? That’s true. But what I want to say is that God was there in the midst of all of it and he was there even when I didn’t recognize him as such. And so when I come to these points in the book where I talk about that they may even feel like eruptions. ’cause there isn’t like a slow build, it’s just chapter, chapter, chapter God and then chapter, chapter chapter God. But that’s how my life was, right? And if You know me, if you hang out with me, you don’t hear God. Every other sentence, I might be talking about the Lakers or LeBron James or whatever. And sometimes I You know the God bit comes out of me.

Esau (22m 56s):

And so to have an authentic book that allows the complexity of my life to come forward, that gives other people a reason to be complex because some people think I’m either talking about God or I’m talking about race, or I’m talking about poverty, I’m talking about injustice. I’m talking about spirituality. But we don’t get to carve our lives up like that. We’re a a jumble of things. And hopefully my story gives people permission to be a jumble of things.

Amy Julia (23m 21s):

I think it does give that permission. And I wanna ask you a question about one moment where maybe that will maybe bring this alive for listeners a little bit because there’s a scene where it’s your junior year of high school, And, you blow out your knee in a football game. And so You know that the prospect for playing division one football in college and getting a scholarship for that like have just become slim. And it was pretty clear that that was going to happen. So I’m gonna read this is part of your prayer that night you wrote that this is what you prayed to God. Surely you wouldn’t leave me with a useless knee and broken dreams. You owe me, I can’t end like this. And then you also write that your mother prayed a different prayer that night.

Amy Julia (24m 5s):

Yeah. And I’m just curious now you’re an adult, you can look back on your story and see what happened in some ways as a result of your knee not being what you wanted it to be. Yes. How do you, how do you see those two different prayers now and and what do you think about them?

Esau (24m 23s):

Yeah, so to put a little context, when I tore my knee up, that was my, my chance to go to college I thought was through athletics. And so the prayer was for a miraculous moment of healing. ’cause I’m from a tradition where people like God is a miracle worker. He can do whatever he wants. And so I’m thinking to myself, if everyone sees me tear three ligaments in my knee and then the next day I run or the next week I run back out onto the field, look how God’s gonna get glorified by me being healed and returning to my former glory. So I prayed that prayer. Yep. And then I said, okay, God, I’m now gonna walk like you take your mat, you like take up your mat and walk. And so I put the, the, the, the, the crutches to the side and try to put weight on my knee and it collapses.

Esau (25m 13s):

And I’m just like, I can’t believe God didn’t answer my prayer. And my mother is praying for a different thing. She never prays for my healing. She prays for a doctor because we don’t have an insurance. She prays for a doctor who can do the surgery for free. ’cause we couldn’t afford to have the surgery. And God actually answers my mother’s prayer And, she and God doesn’t answer my prayer. Hmm. And there a doctor kind of shows up miraculously and I get free rehab and all of these other things. But what I learned is like sometimes the miracles don’t take away the problems. The miracle is that God allows you to live another way. The miracle is, is like manna in the wilderness to kind of keep you until you get to where God wants you to go.

Esau (25m 56s):

And I can say now in Providence, I can see God’s wisdom. If I don’t hurt my knee, then I don’t go to the college that I go to. I don’t meet my wife, I don’t meet don don’t have the spirit spiritual experience that I have to make me to the person that I have. I never discovered that I’m a writer, writer. And so there are tons of ways in which, what’s that God re God used my injury to dramatically change the course of my life in such a way that I’ll be more useful to him and to become a better person. And so God used that tragedy to fulfill his purposes.

Esau (26m 41s):

And I couldn’t see it at the time. And, and, and if, and if you had told me that, that this is gonna be the outcome, then I would’ve said, sure God, I will do it. But at the time it felt like God had ban abandoned me. And, and, and the thing that I wanna say is the miracle is not that I returned to my former glory. I never became that athlete again. The the miracle is that like the future that I had planned for myself wasn’t the future that God wanted me to have. And God in his mercy used the tragedy. I’m not saying he costed to be used the tragedy to make me into the person he wanted me to be.

Amy Julia (27m 26s):

Well, and that’s something that comes up at that section in the book. And again, I think you do this in a really deft way in terms of exactly what you just said. Not trying to look back and be like, oh God, You know, reached down and snapped the ligaments or something like that. but you do write that one of the things, one of the things you recognized at that time was that you were more than a black body. You had a black mind. And it seemed like that was really important because up until that point you’d gotten good enough grades to be able to survive in school from what I can tell. but you had not kind of turned on your intellect. And that, and I, I’m sure there were multiple factors going on there, but I’m curious about like why it was so important for you to know that you were more than a black body and then also just at the same time you also knew that you wanted to go to college and the way to get there was through sports.

Amy Julia (28m 19s):

So there’s a little bit of a tension there at the same time that, so yeah. Can you just talk to about that a little bit? Yeah. So

Esau (28m 26s):

A lot of times people try to think about athletes as being people who are chasing this, this very unlikely dream of becoming a professional athlete. A lot of people who I knew who yeah. Wanted to use sports to get to college. And because we knew other people who had used sports to get to college, that was a clear path. And at my school, for example, nearly half the seniors on the football team actually probably closer to three quarters, but people will say I’m exaggerating. So I’d say half the seniors on the team who started got scholarships. So if you went to that school, And, you started on the football team, you, you were started for two years at the end you normally got a scholarship.

Esau (29m 11s):

So it was a pretty secure path to college. Yeah. And I knew people who had gone to college, so I said, okay, I can go to college. And since I was a reasonably good, the the bar for a football player is pretty low. You have to kind of have a minimal G p A and a and minimal grades like a two, five or something to get into college. So I said, okay, I know that I’m good enough to go to scholarship, only have to get this grade. So it’s all I ever tried for now, because I was a decent student, I actually was an above average academic athlete. So I could get recruited by places like Vanderbilt, like kind of slight like nerdy football.

Esau (29m 52s):

But it was still a combination in my head of my athletic ability and my brain. I never thought, well why don’t I just cut out the middleman and put the football aside and just do better and go to Vandy. I was like, oh, if I do well here, I can even go and do like, or an Ivy League school. There’s these ideas that basically I didn’t have the grades to just apply to an Ivy League school, but for a football player I did pretty well. Now once football was gone or I thought it was gone, I ended up, I ended up playing in, in college. I don don’t know why. I just didn’t click in my head until then. Well now the only way for me to get there is through my intellectual ability.

Esau (30m 33s):

Yeah. And it was that moment of having sports taken away from me for a season that I really had to see what I could do intellectually. And I discovered much to my surprise that I was a better student than I knew. And, and, and for me that idea that I was more than just a body that You know who, who was just, who’s willing to do You know to, to run into people and to throw people on the ground to get to, to, to get to college, that I could think my way to college was something that was important to me. But, but I, but I guess, yeah.

Esau (31m 13s):

And it seems like in, in that story, I want to say though, it’s easy to dismiss this unless you live in a community where you don’t see very many college educated people, And, you don’t see the path to get there that this really straightforward, you say, why didn’t you just do your work? Well, who was I gonna, who, who did I know who is this college educated person living in my neighborhood? I was the first male from my family to graduate from college. My sister who’s two years older than me was the first person to graduate from college. Not just amongst my si like amongst my extended family. And so we didn’t have a picture of it, but I knew people who had gotten scholarships.

Esau (31m 57s):

And so for me it was profoundly logical to put all of my hopes in sports.

Amy Julia (32m 2s):

Yeah. And I think it’s an interesting, on the one hand, it’s like can be reductionistic, right? To only see yourself or have other people see you as valuable because of what your body can do on a field. Yeah. On the other hand, it’s really expanding your possibilities to have a way to imagine going to college. And so there’s a, there’s a both and happening there. And I think we just want to create more and more conditions where the imagination is shaped by possibilities. Whether that’s intellectual and physical one or the other, both. And, but You know you want, you want more and more of that for more and more kids who are in a situation where they might not have that in their family, but it still is actually possible.

Esau (32m 48s):

I called it a gateway drug. And so I wasn’t the only person who, right?

Amy Julia (32m 52s):

Yes.

Esau (32m 53s):

Used forces gateway drug into education. There’s tons of people who, who stayed in school just to play football or basketball or baseball. And then because you gave them something to hope for, but in the process of staying in school, they found themselves. And so when we dismiss athletics, we don’t, because of the long odds, we don’t see it as a way to give people hope. So there’s tons of people who didn’t become few. Like there’s two people from my school who in the N F L three, maybe I think three in during the 2015 years that I was around in Huntsville or, and, and so of course 15 out of You know hundreds and hundreds of athletes is not very many, sorry, three n f l players out of hundreds and hundreds of athletes.

Esau (33m 40s):

Yeah. Aren’t very many. But how many of us stayed in school because our coach said, you have to, you have to stay eligible. Then they got to their senior year and they said, oh, I might as well graduate. And then they say, oh, I might as well go to college. And so it was a way of keeping us invested until we found ourselves. And I just found myself in a much different way than I expected. But I don’t think I would’ve ever gone to college had I not been an athlete first. ’cause it was athletics that, that had my imagination for such a long period of time.

Amy Julia (34m 13s):

Hmm. I love that. Thank you for kind of spelling that out, like weaving those pieces together. I wanted to ask actually as a follow up about hope, because this is a book that has You know instances of trauma and pervasive both kind of casual and more systemic racism throughout it. Fatherlessness, you’ve already told us a bit about that experience with your dad. And yet there I I think this is also a profoundly hopeful book. And so you’ve spoken a little bit about what it means You know for a high school student to have hope, but what for you is what gives you hope? Like what, what keeps you not in some sort of like false or toxic positivity stance?

Amy Julia (34m 59s):

Yeah. But in a place where you can actually hold the real sorrow and loss while also remaining hopeful in I think the goodness and love and purposes of God,

Esau (35m 14s):

You would gold star number two because the only common word, so this is between reading why black title Reading, why Black African American Biblical interpretation is an exercise of hope And the subtitle That’s right, yes. For how parts of the Promised land is one family searched for hope and survival. And so I have been for most of my life, obsessed with the idea of hope because for so long I couldn’t figure out what hope was there. The odds were seen to be so long You know they say you, you’re gonna end up dead and in jail. Yeah. That’s the kind of stuff they said about us in our neighborhood.

Esau (35m 54s):

You’re the kids who aren’t worth anything and you’re not gonna become anything. And, but for some reason I’ve always had a sense of hope that my past didn’t have to define what I became. And I’ve tried to find ways to articulate why that’s the case and what I, I found, and I’m still, there’s another hope related book somewhere in the back of my head that I wanna talk about right now. What I found is I think that hope and honesty are inextricably linked. So sometimes people find hope by shrinking the problem.

Esau (36m 40s):

It’s not that bad, therefore I can have hope. But that to me is a false hope. Hmm. The only kind of hope that God can provide for us. It’s a solution to the problems that we actually have. And so until you face the darkness, you can’t find the light. And so what makes me willing to tell my story as plainly as I can is because it is precisely into that world that God speaks as a word of love and kindness and care. There is no other world for God to come to, other than the world that does this to people. And so the hope that I provide that God gives to me is a hope in the face of real difficult circumstances.

Esau (37m 25s):

So on one level I could just say hope is just my confidence in the power of God. But another thing that I would say is hope is my belief in the power of God to be there with me through the midst of my actual problems, not the ones that I lessened to make it better for God to manage. You know we have this, this, this subtle idea and I, I mentioned it in the prayer that if you kind of hold back And, you can ask God for big things, right? That you don’t wanna bother God all the time. You like, okay, God, I only need two or three big asks for my life and this is where I need you to show up. And that’s what it means to have hope. But no like God is actually not just there during the big ask, but God is always with us through every part of our lives.

Esau (38m 15s):

And I’ve just concluded as a Christian that I believe that the Christian story is true. And if the Christian story is actually true, if Jesus died for our sins and three days later he rose from the grave, there is no problem bigger than the power of God. So we can always tell the truth. We can always tell the truth. And I think that one of the problems that the church as a whole has is that we’re terrified of the truth. We can say, okay, if we’re honest about all the ways that the church is complicit in racism and misogyny, then what kind of Christianity can be there on the other side.

Esau (38m 55s):

But if, if the Christian story is true, then we can be honest about the feelings of the church with the trust that God can solve those problems by his power and by his goodness. And so I’m always trying to help us to trust God enough to tell the truth and to trust on the other side of that truth. Telling is more goodness that God doesn’t exhaust his goodness in solving small problems that God’s goodness is, is abundant. You know there there’s a passage. You gonna met the new Testament scholar in me, that he’s a rich in mercy. God doesn’t have a little bit of mercy, right?

Esau (39m 36s):

He doesn’t have like, oh, I spent all my mercy and grace last Tuesday. Mercy payday isn’t for another two weeks, then I get another friend back. He has a ton of the stuff right? And so my hope is simply, like I said, in the power of God. And I have not found another story or another person that had just captured my imagination and inspired me like the story of the birth, death, resurrection of Jesus as the climax of the Biblical narrative and a point towards the future. That is my hope.

Esau (40m 16s):

And that’s the basis by which I try my best to live my life. And I’m imperfect like any other Christian.

Amy Julia (40m 23s):

Hmm. Thank you so much for that. I, my most recent book was about healing and one of the places I kind of landed in looking at Biblical Healing was that the movements towards healing are honesty, humility, and hope that those three, not always in that order, but are kind of the, like don don’t know if necessary preconditions is to say it too strongly. But that healing comes when we are honest about what is painful and hard and broken and all of those things humble about our inability to fix the problem and that we have needs from God and from one another.

Amy Julia (41m 3s):

But hopeful that that story is true. That those things can actually, that healing is possible, that change is possible. And that when you put honesty, humility, and hope together, healing does begin to happen. And I’d love to maybe end with one more story. And, you can tell as much or as little of it as you want to. But I was really struck by, again, a hopefulness that I saw as a story of healing towards the end of the book. When you tell the story of your wedding And, you write about, this is a quote, the church doing its work. And I wondered if you would be willing to talk about the ways you’ve seen the church do its work, perhaps sometimes in unexpected places and through unexpected people.

Esau (41m 50s):

Yeah, it’s funny, it’s, that’s one of my favorite chapters. It’s about, it’s called Fools Fall in Love. And it’s a story. It’s,

Amy Julia (41m 59s):

And I told you I wept while reading it. It was so good.

Esau (42m 5s):

It’s, it’s, it’s like I Amy I’m just, at some point I just, I was just being ridiculous in this book. And what I mean by that is there’s a chapter on police violence and then there’s a love story right in the middle of it. You know, like, like in the book, like I was like, okay, well that’s

Amy Julia (42m 21s):

Also your life, right?

Esau (42m 23s):

It’s my life, it’s my life, right? These are things that happen. And so I’m once again begging the audience’s indulgence where I tell a love story in a chapter and it’s called Fools Fall in Love. And it tells the story of how I met my wife and what you, what you have in mind is when we were getting married, we didn’t have any money to pay for the wedding. And we, the church kind of surrounded us during that moment. I was just a broke youth Pastor And, she was in medical school, so she was just a student. And so it was this, it was this tiny white, all New England, sorry, all white New England church and all of the ladies at the church, ’cause we couldn’t afford, what do they call it?

Esau (43m 11s):

Catering. And so all of the ladies at the church brought their old New England fine dining, fine China. And each one of the tables, yeah, in the church were decorated with the fine China from all of the families in the church. And the food that was there were the old church ladies who went and made a bunch of casserole and all of the food and their best meals. And so the food from the church was actually the food that the, that the congregation cooked the wedding cake. My mother had flown in for the wedding was the German chocolate cake that I used to eat as a child. And so my mother flew in the day before, made the German chocolate cake as the wedding cake.

Esau (43m 54s):

And even the flowers, we couldn’t afford the floral arrangements. And so it was in the England church used to force sunny of advent. So there’s like these red poinsetta that are often around. And then in New England they had this thing called the greening of the church where they kind of put extra greenery around to make the church beautiful for, for Christmas. And so they actually put the greenery on a few days earlier. My, our wedding anniversary is a few days before Christmas. And so the church is decked out and like this beautiful red points at us from, from Advent and it had like the greenery getting ready for Christmas and then like it, it, it’s like it’s, it’s, it’s a evening wedding.

Esau (44m 38s):

So we walk from one part where the chapel is onto where the food is. It’s like snowing in New England And. you go in and it’s just this candlelight dinner of all of this fine China and it looks amazing, but we’re all broke. Like we, we didn’t pay for any of it. And it was to me, a and we like we’re both southerners and like I’m this black guy and this all white congregation really showed me and my wife the love of Christ. And it was one of the times where it was the first time since I had been in Huntsville, Alabama at the ba, black Baptist Church that raised me, that I felt like I was in a church that was an actual family.

Esau (45m 23s):

And that was in a totally different context. I remember when I first got there, they couldn’t even understand me and I didn’t understand what they were talking about. I’m gonna, I wanna do a bad Boston like in the car and get some chowder. Like it was like, and I was like, what’s going on with your southern accent? You know talking about, I never forget they, this is a complete, so this is a deep New England cut, but they had this place called Gloucester and if You know how Gloucester spelled, it’s called Chester. And it’s like, I’m like, where is Chester Whatcha talking about? I was like, no, it’s, it’s, it’s, it’s Gloucester. And so it’s just like there’s this whole time where like we didn’t know what to do with each other, but we became a church family there.

Esau (46m 6s):

And, and, and that, that moment to me has always struck me. I think everybody thinks that wedding is the best wedding, but I’m gonna argue that if you read it, you’ll say that our wedding was the best wedding and everybody else, y’all just gotta have to feel bad and, and, and wonder why your church didn’t do y’all like we would die.

Amy Julia (46m 26s):

I love that story so much and I really did like cry when I read it because I am in one of those You know essentially all white New England churches with lots of little old church ladies and who can seem kind of like they’re not up to date when it comes to politics and You know, trying to have conversations about racial justice might not go very far. And yet there is a sincere love for Jesus and for people and a willingness to like really go all out in order to honor people well and I just love that picture of your mom there with her German chocolate cake and the You know little church ladies with their China and that sense of really being received and celebrated for who you are and and for who your family would become.

Amy Julia (47m 18s):

’cause you and Mandy have gone on, have four kids and I’m sure that those ladies are happy about it.

Esau (47m 23s):

Yeah, I was nervous about that chapter because once again, you don’t expect a love story to, to break out in a book like this. You want it to be all sad and somber and And you getting there. And if people read that chapter, they will see that that’s the story’s more complex than I told here. But giving yourself space to talk about once again, something that’s important to you. And what was important to me is the fact that I fell in love and that I’m married and that I became a father and I then had the opportunity to to, to chart a different course for my family and my children.

Esau (48m 5s):

And that is an important part. And I’m not, I understand that people can be healthy and happy and whole apart from being married. I’m not talking about like marriages, the completion of one’s life vocation. I’m not saying any of that at all. God, can God bless you if you’re single? God bless you if you’re married. That’s not what I’m saying. But I’m saying is that in my narrative, the the, that my relationship with my wife is an important part of the story. And and getting space to tell that kind of complicated story is once again a part of what it means to be human, right. Who, who do we, who do we spend our time with and how do we make sense of the sacrifice that comes with meeting someone who is different from you has their own own hopes and dreams.

Esau (48m 50s):

And now that collision of two different hopes and dreams and ideas of the future, out of that, out of that collision comes something like what we might call a life in a marriage. And so I, yeah, I really like fools fall in love. I’m glad that you liked it. I’m glad that you liked it. Oh

Amy Julia (49m 7s):

My, my gosh, I loved it. I I literally, I took pictures of some of the pages and sent them to my husband just as a, like this is what marriage is all about. I loved it. But I also think what you just said speaks to And. we don’t have time to get into this, but I’m just gonna leave it as like a teaser for listeners. but you also do a great job of insisting the, the story of being black in America is not only a story of travail, right? It is also a story of joy. And that’s really important. And I think that’s something you’ve done well, not only in this book and in telling the celebratory moments, but also in the New York Times when you’ve written there. And I think of, I go to a camp in the summer with my family, You know our oldest daughter has down Syndrome.

Amy Julia (49m 47s):

And so it’s a camp for families affected by disability and on the last night of camp that they Host something that they call a Luke 14 banquet based on the parable in Luke 14 when all the people who are not expected to be invited to the wedding banquet are invited. And they come in and sit down together. And one of the things that happens at that banquet is that they serve dessert first and the hosts of the camp who have, in one case Catherine had a stroke and has a disability And, she says, yeah, we’re eating dessert first because we want it to be clear in the midst of a life that for many people here is filled with suffering and hardship. Do not wait to celebrate. We’re gonna celebrate right now for the life you have right now.

Amy Julia (50m 31s):

And we’re not denying the suffering in it, but we are also going to celebrate together. And I think that story of your wedding is, and, and just speaking and writing about black joy, all of those things weave together into this what you were talking about when it comes to hope, that it’s very honest and yet it also insists and continues to insist on the goodness of God and on a story that is not, has not been finished yet, that we are all a part of. So I just wanna thank you for giving us your time today, for giving us your words in this book. And yes, if any listener has not already stopped this podcast and gone out and bought your book, I’m gonna tell ’em they should do that right now because I got an early reader copy and I, the only reason I was annoyed about that is that I couldn’t buy it for friends and hand it out left and right.

Amy Julia (51m 18s):

But I’ll do that when it actually comes out.

Esau (51m 20s):

Thank you. It comes out I think in September, September 12th.

Amy Julia (51m 25s):

Yeah. So we’ll, we’ll air this podcast closer to when it’s coming out. So it’ll be available either very soon after this podcast airs or it’ll already be available ’cause we’re gonna, we’re gonna hold it until September.

Esau (51m 36s):

Oh, thank you. So I wanna say you are a good interviewer because you took the time to read and to think about the book And, you helped me understand some of the things that I was doing. I didn’t even notice a thing about my, my name and how it carries a bunch of different themes in the book until you said, I was like, oh, that’s actually correct. All of these things are tied together. So thank you for being a careful and generous reader. And stories are complicated and, and the vulnerability of our stories are complicated And, you share a little bit of yourself in the hope that it helps other people find themselves.

Esau (52m 21s):

And so if I managed to succeed in doing that and, and in the course of finding themselves, hopefully find themselves a little bit closer to God, if I managed to succeed in doing that, then it was worth the effort. And so thank you for reading it. Thank

Amy Julia (52m 34s):

You. Thanks as always for listening to this episode of Love is Stronger Than Fear. We rely on you to spread the word about this podcast and that happens anytime you share it with a friend or give it a rating or review. And that’s especially true at the beginning of a season since we are about to drop the Podcast very regularly every other week for the duration of the fall. So now is the time, and gosh, I mean this conversation is the one to share with people. So I’m just gonna urge you right now to take the five seconds that it would take to pause and hit that little button and text it to a friend or put it on a social media page and let other people know about what’s happening over here.

Amy Julia (53m 20s):

Or this is like totally going the extra mile I know, but actually heading over to the Podcast itself and rating or reviewing it. I would love that. And I would also love to hear from you directly. My email is Amy Julia Becker [email protected]. So next time I’m going to be talking with Curtis Chang about his new book, the Anxiety Opportunity, and just a little bit of a preview. I’ve got more conversations about hope and healing throughout this season with guests lined up like Kurt Thompson and Tish Harrison, Warren Warren, and other just wonderful conversation partners. As we conclude today, I always wanna thank Jake Hanson for editing this podcast, and Amber Beery my social media coordinator because she makes everything happen and I’m so grateful for her all the time, every day really.

Amy Julia (54m 10s):

Finally, as you go into your day today, I hope you’ll carry with you the peace that comes from believing that love is stronger than fear.

[podcast_subscribe id=”15006″]

Learn more with Amy Julia:

- To Be Made Well: An Invitation to Wholeness, Healing, and Hope

- S6 E22 | Why Stories of Hope Subvert Racism with John Blake

- S6 E4 | The Beauty of Life Together with Willie James Jennings

If you haven’t already, you can subscribe to receive regular updates and news. You can also follow me on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Pinterest, YouTube, and Goodreads, and you can subscribe to my Love Is Stronger Than Fear podcast on your favorite podcast platforms.