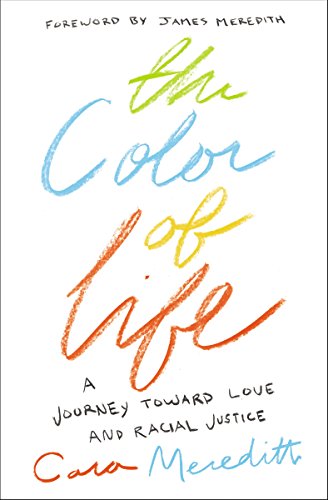

Cara Meredith’s new book, The Color of Life, is a memoir about race, justice, and love. I so appreciated Cara’s story—her marriage to James Meredith, a black man who came from a prominent southern family, and her journey to understand racial identity and love as they began their own family together. Cara writes with candor and grace. I hope you’ll check out her book. Here’s a short glimpse at some of the ways she has sought to make small changes, in this case, in terms of seeking out friends who come from different ethnic backgrounds than her own:

It was just another night at our dining room table, or so I thought. Three other couples gathered with my husband James and me for an informal night of friendship and conversation. We ate taco soup loaded with and cheese and crumbled tortilla chips; we clinked glasses of wine and laughed so hard tears rolled down our cheeks.

A funny thing happened that night, though: I began to notice those sitting around the table with us, maybe for the first time. James wasn’t the only person of color in our home that evening – instead, a Latinx couple, a black couple and a white couple gathered with us. We shared a commonality of being new to the institution of marriage, new to unearthing simultaneous feelings of exhilaration and loneliness that come with saying yes to the one who holds your heart.

But in that noticing, I also felt a kind of exclusion, the majority for once becoming the minority, at least for a single evening. As I write about in my new memoir, The Color of Life, that night changed the way I interact with the world around me, for I saw firsthand the common bonds of injustice:

“Theologians and philosophers often call it a commonality of oppression. If I were to dust off an old book from seminary, I’d remember that in liberation theology, the eyes of culture always count, for the oppressed are always on the lookout for a redeemer, a liberator, a savior of spirits and souls. As we ate together that night, soup dribbling down our chins, the stories that rang solely of injustice to me became a common, binding experience for those who shared their pain aloud. The “I” became the “we,” the tangled roots of oppression and injustice the stuff of shared experience.

“As a white woman who lives and breathes a predominantly white existence, I have never – nor will I ever – experienced oppression, at least not because of the color of my skin. I might see the effects of racial oppression firsthand because my life is intertwined with a man who has fought against the grave realities of injustice, but I will never fully experience what it means to be slighted for having darker skin” (81).

I started noticing something new that night – a noticing of who was and wasn’t sitting at our table, a noticing of who had and hadn’t been invited to join us for a meal. Years later, I would read about a study from the Public Religion Research Institute that confirmed the normalcy of my friendships. Although the study is nearly five years old now, the report mirrored my experience when it reported that “in a 100-friend scenario, the average white person has 91 white friends; one each of black, Latino, Asian, mixed race and other races; and three friends of unknown race. The average black person, on the other hand, has 83 black friends, eight white friends, two Latino friends, zero Asian friends, three mixed race friends, one other race friend and four friends of unknown race.” My own journey, one of equal parts comfort and ignorance. I suppose that’s when I began to notice who hadn’t been sitting at my table all along.

So, I started to do something about it, because when it comes to taking steps toward combating racism and fighting injustice, noticing matters, but doing something about this noticing matters even more.

After all, if we only fill our tables and our living rooms and our backyards with people who look and think and act mostly like us, then we miss out – for we know and we are changed by the stories we hear, by the accounts we read and by the tales we absorb.

And I don’t know about you, but I’m hungry for a little bit of change to happen in my heart and in the world around me.

If you enjoyed this post, I highly recommend that you read Color of Life. If you are interested in other books on race and breaking down barriers, you might enjoy my book, White Picket Fences. If you would like to be exposed to different perspectives, check out this book list.

This Post Has One Comment

Hello Cara and Amy Julia,

It’s good to hear your thoughts. I don’t have anything concrete to base this on, but I lean toward believing that the white women of our country are the voices that may have the power to speed up change more rapidly than the rest of us. This is because the place of the white male is still firm at the top. He has no reason to be enthused about giving it up. The minorities of the country continue to scream in order to be heard even a little. Ahhh… but the white woman, who has white husbands, brothers, fathers, etc., and who is worshipped by them, may have a chance to be heard… if she is brave enough to come off the pedestal where she’s been placed, and to open her mind to formulate her own opinions, as opposed to following those of her mate.

All generalizations here, of course. I see this mostly in my many white women friends who are older than 50, as I am.

Hmmm…