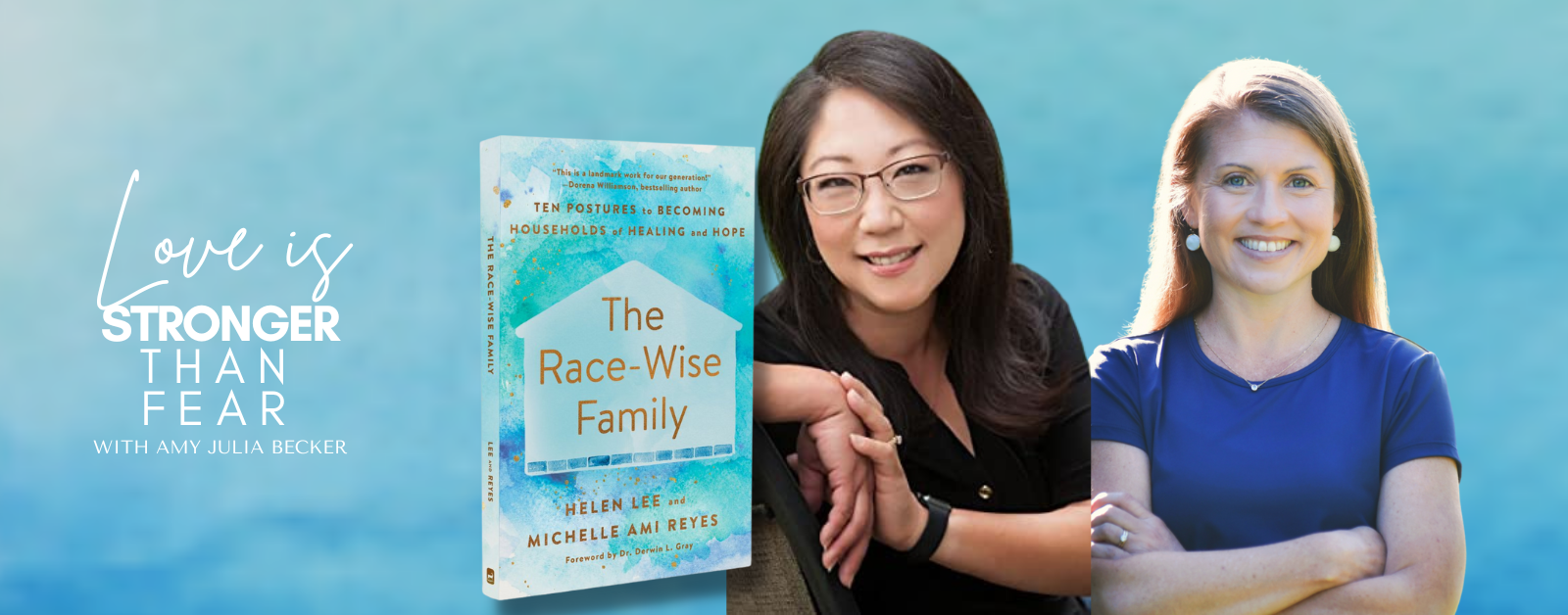

How do we raise children who will stand against racial injustice? Helen Lee, co-author of The Race-Wise Family, and Amy Julia Becker discuss why it’s important for all of us to talk about race, how we can do this well with and for our children, and the postures of celebration and lament.

Guest Bio:

“Helen Lee has been a Christian publishing professional since 1993, when she began her career working at Christianity Today (CT) magazine. She is the director of product innovation at InterVarsity Press, where she formerly served as an associate editor, director of marketing, and associate director of strategic partnerships.”

Connect Online:

- Website: helenleebooks.com

- Instagram: @helenleebooks

- Facebook: @helenleebooks

- Twitter: @helenleebooks

On the Podcast:

- The Race-Wise Family: Ten Postures to Becoming Households of Healing and Hope by Helen Lee and Michelle Ami Reyes

- The Story of Juneteenth by Dorena Williamson

Interview Quotes

“Your faith and your ethnicity are two parts of your identity that can go hand in hand.”

“We try to make it a very consistent thing to talk openly and freely about our ethnic heritage and how it’s a gift. Now, there are things about our ethnic heritage that, of course, you know, there are pros and cons to everyone’s cultural backgrounds, naming that, understanding it, talking about it, owning those things that can be challenging or harmful as well as the blessing of the way that our culture has shaped us—noticing all those things and being willing to talk about it.”

“As we continue to get to know just the range of people’s stories around us…it starts to sharpen our own awareness and our understanding.”

“Even that question of trying to name what is an American culture is a little tricky because it could be very different the way I experienced it from the way you experienced it or someone else experienced it.”

“[Children] may not understand what it means to be in the majority culture versus being someone who’s a person of color and what those distinctions even mean. Talking about it gives permission to be asking those questions and having those conversations. So that’s, I think, an important door to open, even when they’re young, because this question about what does it mean to be an American?”

“And I think that the key thing about lament and why it’s important for us as Christians and as families to engage in that practice and posture is it just softens our heart. It opens us up to become more compassionate to the stories of people around us.”

“[Lament] can move you at a heart level to really start resonating with the injustices and pains and sufferings and evils of the world in a way that your head sometimes can’t quite get there.”

“We don’t often take the time to lament some of the harder parts of our history, the darker parts of our history. And that’s part of our journey of transformation is being willing to be open to seeing the truth, both the good of who we are as Americans, and also the hard, hard parts of our history that…I think we are still reckoning with. That’s an important part of this process of becoming a whole and reconciled people.”

“God does not give us a spirit of fear. He gives us a spirit of power and love and truth. So I have to believe that when we are experiencing fear in talking about this issue, that’s not from God. And I do believe that is one of Satan’s huge weapons that he is using right now in the church to prevent there from being either conversation or progress in the area of racial reconciliation.”

“The issue is not that there’s not resources out there…there’s so much out there. It’s usually just more about initiative and intentionality. So I think if Christian parents just are willing to take that intentional time to look and see what’s out there that would be age-appropriate for their kids in their families, do some learning on their own as well, do a little reading up beforehand—those are things that are anyone can do….It really just is a matter of will and willingness to take the time to prepare and to learn.”

“As you are praying out of the sincerity of your own heart lamenting things you’re seeing on the news, naming some of the injustices and realities where you need and want to invite God’s justice to reign, expressing those moments of lament, expressing solidarity with those who are suffering—as parents, I think that’s incredibly powerful for our kids to hear us being willing, to verbalize those cries of our heart and soul in this particular area.”

“As parents, I think that’s incredibly powerful for our kids to hear us being willing, to verbalize those cries of our heart and soul.”

“The process to becoming a race-wise family starts with parents being willing… to take that time, to open up their own hearts, minds and souls, because it’s not going to always be comfortable. It may actually be painful at points as you start confronting maybe areas of your own bias or areas of your own ignorance or areas where, you know, you need to repent of certain things or you have to own and name your own privilege…So this is not a comfortable journey at times. It’s not, but what’s on the other side of that!”

Season 5 of the Love Is Stronger Than Fear podcast connects to themes in my newest book, To Be Made Well…you can order here! Learn more about my writing and speaking at amyjuliabecker.com.

*A transcript of this episode will be available within one business day, as well as a video with closed captions on my YouTube Channel.

Note: This transcript is autogenerated using speech recognition software and does contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Helen (5s):

I think that’s incredibly powerful for our kids to hear, speak more willing, to verbalize those cries of our heart and soul in this particular area. And being able to acknowledge, you know, God, I don’t know what to do about this. Like, I don’t know what to do by this continuing injustice that’s happening against black and brown bodies or naming those realities. I just being able to do that so that your, your kids can see the sincerity of your own journey. I think that is incredibly, incredibly powerful.

Amy Julia (39s):

Hi friends, I’m Amy, Julia Becker. And this is love is stronger than fear. A podcast about pursuing hope and healing in the midst of personal pain and social division. Today, I’m here with Helen Lee, an editor at InterVarsity press and co-author of a new book called the race Wise Family. I was really grateful for this conversation and especially for me personally, I was grateful for Helen’s description of the practice of lament and why it matters for all of us to learn how to lament as individuals, as families and as communities. And we also got to talk about why talking about race is important and how we can do this well and how we can do it with and for our children.

Amy Julia (1m 22s):

So I hope you, like, I will find some practical ways to become a race Wise Family, as you listened to this conversation today. Well, I am sitting here today on zoom with my friend, Helen Lee, who is the co-author of the recently released a book that so many people who are listening to this podcast are going to be interested in this book is called the race Wise Family, 10 pastures to becoming households of healing and help Helen. Welcome.

Helen (1m 55s):

Thank you, Amy. Julia, it’s such an honor to be with you today. I really appreciate it.

Amy Julia (1m 59s):

Well, I have to tell you, I was ready to end this podcast for the summer and I’m going to do that soon, but then your book came out and I was like, oh, I can’t pass this up. I’ve been waiting for this book for like two years since I think I first learned that you I’m in at the time. I don’t know if I knew you were co-authoring with Michelle res, but I just knew the title of the book. And I knew you. And I knew that I wanted to read it because I know that you have been living out and thinking through all sorts of issues related to race and ethnicity and family and faith. And you’ve been doing that for a long time. So I’m just really grateful for parents like me, who get to learn from your wisdom and your experiences.

Amy Julia (2m 43s):

So I thought maybe as we start today with people, listeners who aren’t familiar with your story, can you talk about how your own experiences, your own background led you into writing the race Wise Family?

Helen (2m 56s):

Yes. Sure. I’ll try. I’ll try to do that succinctly. But when I think of my own journey of faith, I look back particularly in college when I was involved in InterVarsity Christian fellowship and that college ministry had a huge impact on me, but the pivotal moment even amidst that journey was when I met a group of Asian American staff who were the first people that articulated for me that your faith and your ethnicity are two parts of your identity. And he, that can go hand in hand. I had been in this mindset at that point in time where I kind of wanted to reject my ethnic identity. I had had enough struggles with feeling like I didn’t fit in as a Korean American.

Helen (3m 40s):

I felt a little bit ostracized because of my identity. I had been teased and bullied many times as a kid because of the fact that I was Korean. So I grew up not wanting really to have much to do with my ethnic identity. And so it was incredibly healing to meet people who helped me see that God’s intention to create me as I am, as someone with Korean ethnic heritage living in the United States, but, but fully a hundred percent Korean by blood was not a mistake. Wasn’t an accident. It wasn’t a curse, which is kind of what I thought growing up for many, many years, even through college. So that was an incredibly healing healing message.

Helen (4m 20s):

And as I started to really embrace that concept and then start to communicate that out to other students. And I actually stayed at Williams college where I went to school for a couple of years on staff with InterVarsity leading an Asian-American small group that I had started that experience of seeing how God was using that message of like reconciling one’s ethnic identity and racial background with their faith. That turned into an incredibly evangelistic message actually for a lot of people, a lot of students that I got a chance to work with and serve and get to know over time who had never heard that message before. And similarly, similarly, for many of them, they had grown up like me.

Helen (5m 1s):

I can context where they either were one of the few people of color or one of the only Asian Americans or whatever it might be, but that same feeling of tension inside of wanting to kind of reject their own ethnic heritage. So I was glad that I had a chance to learn that message myself. I was grateful, and I’m very glad also to pass that audit. So that’s kind of the origin in some ways that goes back decades, right? But that’s probably for me the beginning of my journey of understanding issues of ethnic identity and one’s heritage and culture. And of course we all have a culture, right? Not just people of color, we all have some sort of ethnic heritage and to, as I continue to move on in my life and professional work, just trying to make sure that I had opportunities to articulate that sometimes we, especially, if we are from like a majority culture or a dominant culture, we might not be aware of our own kind of cultural heritage and ethnic and how important that isn’t our own identity.

Helen (6m 1s):

So I feel like that’s kind of the lens I bring to this conversation is someone who at least for the last three decades has really learned so much about how understanding one’s ethnic heritage on what understand what’s called cultural background, how much that can deepen and enriching your faith journey. And that kind of intersects with all the things that get mentioned in this book to try to communicate that to other families.

Amy Julia (6m 25s):

Yeah. So thank you. I really love hearing that. And I’m curious for you that introduction leads me to two questions. One is to ask how you have with all that in mind raised your sons differently, because presumably there was something about both the faith context in which you were raised and perhaps also the family context, and obviously just the wider American culture, essentially saying you should assimilate, which is to become like the majority rather than embrace and celebrate your distinctive ethnic heritage and what that might actually be as an American, what you might bring to the table, so to speak.

Amy Julia (7m 9s):

But I’m just curious whether they’re intentional ways. And I know in some ways this is what your book is about, but nevertheless, like if you can think of some ways as a mother and as a person of faith that you’ve been like, okay, so we’re going to do this differently.

Helen (7m 22s):

Yeah. So when I grew up, so I’m, I’m the daughter of immigrants. I’m second generation. My parents were the first generation to come over from Korea. And then I was born here in the U S and interestingly, when I was younger, I spoke Korean first, apparently. But then when Mike got into preschool, my parents were actually told by a teacher of course, times are different now. And the way we think about languages and how babies and children can internalize language. But what my parents were told at the time was you need to stop speaking Korean to your daughter. You need to make sure she stopped speaking Korean to you because then she will not be able to stick with us and learn English and be on pace with her peers. And so of course my parents at that point were like, okay, you know, no, you don’t have to speak Korean anymore.

Helen (8m 6s):

We’re going to definitely let you speak English. And so that’s kind of one marker of how I was raised as a kid to almost the very, very beginning, like what I was at preschool or to start kind of separating myself from my own ethnic heritage. And then my parents as being immigrants and busy and just literally trying to survive, you know, day to day, year to year, we didn’t have conversations, never had explicit conversations about my own Korean, this, and if anything, what I absorbed as a kid, it was my eyes that looked almost like critically at my own culture. There were things about it that bothered me. There are things about it that frustrated me a little bit of what I would call kind of the Confucian influence in Korean culture, which led to some paternalistic or patriarchal kinds of cultural markers, which I didn’t want to be a part of my life.

Helen (8m 58s):

Things like that. We had a kind of a very traditional Korean household where my mom did all the housework. She did all the cooking and my dad, his job was to go to work and then come home, eat dinner, then sit on, sit on this couch and watch his favorite television show. So I was just feeling like, you know, I, I, that’s not kind of something I want for myself. So the big joke in our household was that I was, I was never going to marry someone Korean. I wanted to really separate myself from anything Korean and my parents didn’t maybe they didn’t have the language. Of course they wanted me to appreciate my culture, but I don’t think he was on their radar tick, articulate that, talk about it, communicate about it. So I grew up not having conversations really about my ethnic identity, being a gift.

Helen (9m 42s):

So that’s one thing that we changed pretty, you know, right from the beginning, I ended up God’s humor. I ended up marrying someone who was Korean. I married, I married someone who was Korean Canadians. So I didn’t marry a Korean American. I met,

Amy Julia (9m 56s):

I still managed it.

Helen (9m 58s):

I did. Yeah, exactly. So we, from the very beginning, we’re speaking to our kids in Korean. I’m not fully fluent. My husband is more, more fluent in language than I am, but we did kind of the opposite of what that teacher had told my parents, where he would speak to our, our oldest son and when he was born exclusively in Korean for two years. And I spoke to him in English and that’s my most natural natural language. But yeah, from the beginning, we just wove in communication about our culture, appreciation about our culture, just delighting and celebrating in it, right from the very beginning, there’s all kinds of Korean traditions that go along with having kids and celebrating particular milestones when they are a hundred days old, for example, there’s a big party that you usually Korean families will give to their children.

Helen (10m 48s):

Because back in the day, wasn’t always the case that children would make it a hundred days. And it was thought that if you could, if your child could live a hundred days, that gave him more, her more chances of success in life. So many Korean Americans fan families now have kind of adopted that particular tradition. So you’ll see these hundred day pictures and parties and celebrations one year old, all these different kinds of markers are moments you celebrate in Korean culture that I didn’t experience as a kid, but that we started doing, you know, with our own family and just even articulating that explicitly over and over. And I do think repetition is helpful because it’s not the kind of thing that you, and you know, how it is raising two kids. You’ve got to tell them thousands of times sometimes, and it’s still, doesn’t always get through at least in, you know, when they’re kids, hopefully they’ll remember at some point in time when they grow up.

Helen (11m 36s):

But yeah, we, we try to make it a very consistent thing to talk openly and freely about our ethnic heritage and how it’s a gift. Now, there are things about our ethnic heritage that, of course, you know, there are pros and cons to everyone’s cultural backgrounds, naming that, understanding it, talking about it, owning those things that can be challenging or harmful as well as the blessing of, of the way that our culture has shaped us like knit or noticing all those things and being willing to talk about it. That’s a big thing that we try to do in our family. And hopefully we’ve been able to impart that idea in the book.

Amy Julia (12m 10s):

I’m curious also within all of this, like how so you are certainly raising your sons and have kind of, re-imagined not imagined, but re understood yourself as a Korean American and not as someone who’s trying to leave that Korean behind and simply be an American, whatever that means. But I’m curious also though, in this new posture of, as you said, celebrating heritage and going back and saying, we have traditions and we have food and we have ways of being, we have a language, all of this matters. How about the American part of that? Like, what does it mean for you and how are you teaching your sons about being Korean Americans? You know, that, that, that both.

Amy Julia (12m 51s):

And because I know that it’s really, like, I I’ve been thinking about this as someone who is called white, right. Because my skin color and my ethnic heritage, which is a mishmash of European nations way back, like 400 years ago. Right. So I’m one of those people who doesn’t always know what it means to be, have an ethnic identity and I, and how to pass that along to our children. My husband, actually, his dad is a Danish immigrant. So it’s a little bit easier with our kids to actually pass along something that feels distinctive. And yeah, my family has been in Connecticut and Massachusetts for 400 years. And so again, there’s a lot of things that are pretty distinctive about the Northeast that we can pass on.

Amy Julia (13m 35s):

Anyway, I’m just thinking about the fact that it would be like erroneous and wrong and more than just a airway to say that you and your sons are not as fully American as my children and I are. And yet because of the ethnic backgrounds that are different, we also would kind of claim being an American, I think, in somewhat of a different way. So I’m curious how you think about that because it’s not the melting pot where we’ve all become the same. Right. And yet there is also a sense of like, but we’re both Americans, like let’s not, let’s not pretend otherwise.

Helen (14m 10s):

Yeah, yeah, yeah. It’s a, what a great question. So it’s interesting because my kids are Korean American Canadian, right? So they have Canadian citizenship as well. So it, it often comes up in the context of the fact that we have, we have the ease, it’s a unique situation, but that kind of ease of comparing and contrasting American culture and Canadian culture. So that gives us kind of a, a framework and a place to have those conversations. I understand not everybody has, that has that framework of that base, but it gives us something to kind of work with in terms of articulating what is American culture. Because I think for most of us, it’s just the water we swim in. It’s the air we breathe. And so it’s not even something that’s easy to like point to or identify, cause it just surrounds us all the time.

Helen (14m 55s):

So I think there, there is something about, as we continue to get to know just the range of people’s stories around this and see how they think about identifying American culture versus Korean culture versus Canadian culture, et cetera. It starts to sharpen our own awareness and our understanding of the fact that, oh, this, this water that I swim in is, is, is not what everybody swims in this air that I’ve read is not what everyone breathing breathe. And in fact, different ones of us in this water swim in it in a different way, or maybe we’re wearing different equipment, or maybe there there’s something different about our swimsuit that allows us to have a slightly different experience in that water.

Helen (15m 36s):

So even giving language to that, even just by just naming that one basic fact, which I think escapes particularly, I think those who grow up in a dominant culture, it’s, it’s easy to think, oh, just everybody has had kind of the same experience. Everyone has been swimming in the same water. So we were all Americans. So we all kind of experienced that the same way. But I think being able to name that, you know, what our experience of growing up here in America may actually be very, very different, you know, from, from someone else. So even that question of trying to name what is an American culture is a little tricky because it could be very different the way I experienced it from the way you experienced it or someone else experienced it. There are of course, you know, things, I think that times when this is going to sound almost really silly, but I, I think that times when we do things like watching the Olympics together, for example, is a time when you can kind of have some of those interesting conversations.

Helen (16m 27s):

And I think families love to watch the Olympics. It’s one of those great moments of, of getting a chance to see lots of different examples of, of national pride, so to speak and kind of even, you know, celebrate what it means to be an American and how that’s distinct in different, but you can even have some of those conversations and commentaries about, oh, okay. So you see all these different nations. And interestingly, when you look at the delegates from the United States of America, they don’t all look the same. There is a diversity there. Why is that? And this is part of the strength of American culture is the fact that we do have that wonderful, amazing range of people from all over.

Helen (17m 7s):

And that’s not to say that other nations don’t have that at all, but there is something unique about the American context that is different, that those are some things that you can start naming as parents with your kids when they’re very young, which again helps them to clue into these, these big kind of ideas of culture and ethnicity and identity identity with something tangible and visual that they are seeing, they are noticing, but they may not understand what it means to be say in like the majority culture versus being someone who’s a person of color and what that, those distinctions even mean, talking about. It gives permission to be asking those questions and having those conversations. So that’s, I think an important stored, even when they’re young, because this question about what does it mean to be an American?

Helen (17m 53s):

It is complicated. It is complicated, but at least naming that there is a thing as American culture. And there is a thing, it was like dominant culture within American culture and it starts to open up. So some of those doors of conversation.

Amy Julia (18m 5s):

Yeah. And I think so much of your book is really about opening up those doors in both, literally, as you were just talking about that naming and noticing without judgment, without simply noticing, you know, this looks different than that, or tastes different than that or whatever it is. But then also bringing some understanding of why, again, what’s the history of those distinctions, how to different people experience them, all of that is going to grow both compassion. And I think perhaps the possibility of celebration of both and, and of lament. I mean, I guess actually, maybe we’ll go there. That’s another aspect of your book that I thought was really important that you write about, you know, 10 postures and we’re not going to have time to talk about all of them, but one of them is a posture of lament and you write about how easily lament can be overlooked or ignored or just not even known honestly.

Amy Julia (19m 0s):

And especially families that have positions of privilege within our culture. That’s certainly true for me within our family where I feel like we’ve lived with economic stability and relative social ease and prosperity. And so could you speak to people like me in terms of what lament is and why it’s important from a yeah. Why it’s important and then also what that might look like to incorporate lament into a household?

Helen (19m 32s):

Yeah. So lament is one of those words that people might want to try to avoid. It sounds sad. I mean, it sounds like something that, why would you want to lament? And yet he read, if you read, even, especially through the Bible and through the Psalms in particular, you see so many biblical examples of lament. And I think that the key thing about lament and why it’s important for us as Christians and his families to engage in that practice and posture is it just softens our heart. It opens us up to become more compassionate to the stories of people around us. And one of the stories I think I told the story in the book, I don’t remember, but I remember that I was in, I was in an inter I I’ve mentioned InterVarsity before, but I was in an InterVarsity staff gathering.

Helen (20m 18s):

It was a multi-ethnic staff gathering and it was right. I think after the right after the verdict of the Eric Garner murder had come out. So I was in this room. We were, we, we, with all the other staff, people, maybe a couple of hundred staff, people of all different ethnic backgrounds. And we decided for that evening to be an evening of lament based on their verdict. So the worship team just led with very soft and quiet meditative music, and then it was quiet. And then we were just invited to pray in whatever way God was moving us to pray. And as I sat there in the silence of the room, initially, I was sitting surrounded by African-American staff colleagues.

Helen (21m 1s):

That’s I just happened to be in a, in a, in a particular place in the room or a right around me. All the people who were around me were all fellow black staff, men and women. And one after another, I just started hearing them sob like one person after another person after another person just started sobbing and not, not even like gentle tears. I mean, heart-wrenching deeply, deeply guttural sounds like coming from the depths of their soul. And of course, I, as someone of Korean descent person who is Asian American here in the U S I do not have the same experience as my black brothers and sisters. So I cannot fully understand, you know, all the payment habits, every single time we have yet another instance of police brutality and a lost life senselessly lost black life in particular.

Helen (21m 52s):

But as I was just sitting in the myths of all the tears and all the sadness, all the anger and all, some of these tears turned and salves turned to screams and they turned to whales and they just turned to, you know, why God, why God, why God, I mean, very, very, just yelling at the top of people’s lungs. And they just needed to get the weight of their, their sadness suffering, all of it just out. I mean, that, that, doesn’t the thing to me in a way that I cannot fully explain something. Of course I knew in my head how hard these verdicts were. Of course, I, I felt deeply the injustices of those moments, but something about being alongside the lemon stations of my black brothers and sisters, as they were, as they were in those women’s of limitation.

Helen (22m 41s):

Just, I mean, it, I mean, it just broke me it in a way that I don’t think any other words or understanding could have, so that’s what lament can do. It can move you at a heart level to really start resonating with the injustices and pains and sufferings and evils of the world in a way that your head sometimes can’t quite get there. And our head knowledge is important. We like, we need to read, we need to study. We need to learn. We need to engage our minds, but lamination engages your heart. And I think that when it comes to this conversation about race, there’s a lot of opinions. And in the church, there are a lot of opinions and a lot of people who think this way about this, or think this way about that.

Helen (23m 22s):

And we don’t all agree, which is fine in the sense that, you know, somehow God will bring all that to fruition in his unified way at the end. But when it’s hard sometimes to maybe convince people, whether fellow believers or just other people in your circles about some of these issues, but lament kind of breaks through all of the head knowledge and all of the, maybe resistance to this idea, that idea, and it just helps you helps open you up to the heart of God and to the heart of others who are, who are suffering in a way that I think changes, changes minds faster than APS, but lament is a really important practice.

Helen (24m 4s):

And it’s something that we avoid as Americans. When you’re talking about American culture, we are talking about the Olympics. I mean, usually in those kinds of settings, it’s all about celebrating the greatness of America. We don’t often take the time to lament some of the harder parts of our history, the darker parts of our history. And that’s part of our journey of transformation is being willing to be open to seeing the truth, both the good of who we are as Americans, and also the hard, hard parts of our history that we have to, and I think are still reckoning with. That’s an important part of this process of becoming a whole and reconciled people.

Amy Julia (24m 38s):

Yeah. And I’d love to pick up from there in terms of so much controversy we’re seeing across the United States in general, but especially within the white evangelical church, when it comes to the idea of race as a, not just a controversial topic, but a divisive one and one that I think there are parents who are, again, people of faith who fear that talking about race and especially talking about the racialized incidents of violence and brutality and systemic injustice that we see regularly in the news, that to talk about that with their children and in church is like signing onto a secular agenda, or, I mean, I’ve seen kind of that’s my, what I see more recently, I feel like when I was growing up within kind of white evangelicalism, it felt more like racist, peripheral to the gospel.

Amy Julia (25m 32s):

So it wasn’t like, oh no, don’t talk about that. That’s secular and dangerous. It was more just like, that’s not the most important thing. You just need to talk about Jesus. Everything else will kind of work its way out. Like it’s an optional topic for like a session in the afternoon, but we’re going to do the core stuff right now, you know, or whatever. Like, so I guess in either case, whether it’s kind of this like benign neglect of the topic or this direct, no, no, no, that’s a scary or dangerous thing. Could you just speak to like how, why this is so important for parents who are, especially who are Christians to be bringing the conversation of racial distinctions, ethnic differences, diversity, and even the harder stuff like the, whether it’s, you know, George Floyd’s death or the recent shooting in Buffalo, New York, or we could sadly, I mean, just list so many different instances.

Amy Julia (26m 30s):

What would, what would you say to parents who are kind of scared about bringing up those topics for all of those different reasons?

Helen (26m 39s):

Oh, wow. Yes. We, we could probably spend a couple hours trying to, in fact, all those things, let’s see if I can give you a couple of summary statements in response. Okay. So this word, fear, I, it comes up a lot, right? When we were talking about this topic and what I’ve been trying to, even for my, in my own mind, work out and then communicate to others, is that when I, what I see in scripture is that God does not give us a spirit of fear. He gives us a spirit of power and love and truth. So I have to believe that when we are experiencing fear in talking about this issue, you know, that’s not from God. And I do believe that is one of Satan’s huge weapons that he is using right now in the church to prevent there from being either conversation or progress in the area of racial reconciliation.

Helen (27m 29s):

So, so w what are we potentially afraid of or what you’re afraid of authorization with our peers? Are we afraid of judgment from other Christians? Are we afraid of getting it wrong? We are going to get it wrong. So we can just like normalize that. Even I, as a person of color, I feel like I stumble along say the wrong things, make the wrong, have the wrong assumption. So this for one thing, let’s just normalize it. That’s going to be a reality. When you start talking about this, of course, you’re going to make mistakes because none of us have perfect understanding of every other ethnic and racial background here in this country and on this planet. So, so let’s try to not be afraid of that, because again, the spirit of fear does not come from, from Christ as when it comes to, okay.

Helen (28m 11s):

There’s fear because we might get judged from other Christians. I kind of feel like you might, and that may be actually evidence that you are on the right path. You know, if you are getting pushback, if you’re having to struggle, because now your friends and family are upset at you, or just think you’re, you know, out to lunch and you’re going on some liberal pathway really ultimately, you know, God is your judge. And as you sit before the Lord and ask him, why are you the one giving me these kind of revelations and these convictions, like, where is that coming from Lauren? I think you’ll find that he’ll be convincing you and reassuring you that yes, you are.

Helen (28m 53s):

You are moving along a path that truly is about, you know, opening my gospel. You mentioned the word gospel, opening the gospel up to the world, because I think the church has been missing the boat on the opportunity. We have to be able to reflect who our broader culture that we have, the answer, the answer when it comes to issues of race and racism is Jesus. And this is what the secular culture lacks. This is where the conversation outside of the Christian faith will be destined to be incomplete. There is no way that the culture can come up with a solution to racism because they’re not able to name what racism is, which is an outgrowth of sin, of course, in the brokenness of our world.

Helen (29m 39s):

And there’s no way that a non-Christian fully be able to provide the solution, which is Christ and the way that Christ can bind all wounds and bring the kind of healing that can restore the nations. That’s not going to come from any human effort. It’s only gonna come from Christ. And so the more that we can as Christians understand some of those just basic, I think they’re kind of biblical theological truth that we try to articulate as clearly as we could in the put to give parents kind of that foundation. So they could trust that as they have these conversations, it’s not just coming out of some secular wind. It’s coming from scripture. I mean, these directives and these principles and the theology undergoing all of this, this whole conversation, it comes from God.

Helen (30m 22s):

And we just celebrated Pentecost. I know this won’t be published until later on, but as the church recently celebrated Pentecost, which my goodness, I mean, you’re talking about a clear as day example of how God uses the gifts of ethnicity. And I think identity to further his mission. I mean, Pentecost is an amazing story of that. And thousands and thousands of people became Christians as they heard their own heart languages coming from the mouths of people who didn’t even know how to speak those languages to begin with. So your God is using this very particular component of ethnic heritage and identity to further the gospel.

Helen (31m 4s):

So it’s true that culture, ethnicity, these are not the gospel, but God uses them to further the gospel. They are part of God’s message to reach the nations, to bring the world to a reconciling knowledge of him. So it’s,

Amy Julia (31m 23s):

Well, It also seems to me that the story of scripture is one of like particularity and diversity, right? That you have this chosen nation of Israel always meant to be a light to the nations. So there’s that. And then once that starts to be even more lived out through the church, in the sense of we’re reconciling Jew and Gentile, it’s not so that they can become the same in their ethnicity, even in the outward manifestations of that in terms of food practices or Sabbath keeping or circumcision. Right. But actually, so that they can become unified in this relationship, reconciled relationship with God, but retain diverse languages and cultural practices.

Amy Julia (32m 9s):

And in fact, celebrate that so that, you know, we get this sense of that’s harder and it’s more true. It’s like more of a reflection of who God is because of the diversity that re remains. Like there’s more of a sense of God’s own. Yeah. Like abundant and multifaceted being when we are able to not just acknowledge our common humanity or for Christians, a common identity in Christ, but actually also say that’s what allows us to celebrate these diverse expressions of that humanity is actually, there’s like a commonality and the diversity.

Amy Julia (32m 52s):

And I feel like sometimes we like fall on one side of that or the other rather than, than holding that together. And that seems pretty central to me, in terms of what the gospel of like the good news of Jesus coming to say, I’m here to like, yeah. To love, to heal, to redeem. And that’s not to make everyone the same, but it is actually to allow us to not be threatened by each other to open up all sorts of possibilities for receiving one another and seeing each other’s yeah. Distinctions again, not as threatening, but as actually gifts to each other.

Helen (33m 30s):

Absolutely. And I think that sometimes parents get the fact that, I mean, demographically, this is a reality here in the United States and especially more so for our kids. So it’s not like a future reality that America is going to become an Anon a non-white nation in like 20 years or so. It’s actually a reality now for those who are 18 and under that population is already very, multi-ethnic very diverse and majority non-white. So our kids are already seeing this <inaudible> depending on where you live, it changes as to how much they’re seeing it, but they will continue to see it more and more as they grow and head to college. They’ll see it even more and more. I mean, this is a reality for our kids.

Helen (34m 12s):

So the more we resist talking about it and engaging the conversation, the less prepared they will be for the reality that they are actually already in right now. So our kids, depending of course, on their, their age can articulate this more than others, depending on how old they are, but they are noticing even babies notice racial differences. I mean, this is like a scientifically proven fact. And so babies are noticing and toddlers are seeing, but no one is helping to give them language to, again, normalize talking about it. Then, then they adopt whatever is in the water they’re swimming in. And that can be a very dangerous thing depending on what that water is telling them.

Helen (34m 52s):

So the more that we can take initiative as parents to be willing, to try to push against the fear we might have about talking about this, pushing against the concern that we may not know all the answers about this, and I may get it wrong. It’s all right. Yes, you may. And you will, as we all do, but it’s more important that you start and make mistakes and don’t start at all.

Amy Julia (35m 13s):

Amen to that. I’m also thinking about when this podcast episode is released. It’s, we’re going to be kind of coming up along what, to many Americans, especially white Americans is a new holiday, like right. We’re coming up on June 10th, which is now nationally recognized holiday, which is a celebration. And it’s, I’ve been struck in my own parenting. That it’s really important for me to, as we’ve talked about name, the injustices of our present and our past and the ways in which race has played into injustice, but it’s also really important to honor the beauty of diversity and to celebrate the ways in which, whether that’s a historical event like Juneteenth or the history of different cultural expressions within American culture have shaped and formed us.

Amy Julia (36m 0s):

Anyway, I’m thinking about Juneteenth just because of the time of year, but I’m wondering if you have advice for parents who are seeking to explain to know what it means to like observe Juneteenth, if you’re not a black American, like, what are we doing as a nation? How do we do this? How have you done that with your own kids? Or what advice would you give to parents?

Helen (36m 21s):

Yeah, I think whenever you’re facing any kind of cultural holiday marker experience where you’re not entirely sure what the best thing to do is then we want to reach out and learn from those who do know, right. So just, there’s nothing wrong with just even observing and, and seeing, and looking with your kids at the ways that your black friends are celebrating, going on social media and even see how some of your black friends are communicating about it. And, and learning from them is super important. Actually, this is not going to be easy in a podcast, but there’s a book that’s coming out by Dorina Williamson on Juneteenth for children. I’m trying to see what date that is ideal on a podcast for me to be looking at my phone.

Helen (37m 2s):

But in any case, I know Doreena has run a children’s books. Adrena Williamson is a, an author who writes children’s books. She’s written the book, colorful, graceful, the celebration place for IVP. I just, some just a small number of the books. And I think her book with Juneteenth is also with IVP, but I’m not a hundred percent sure. So anyway, looking for flux and resources for children, of course, super, super helpful. I always find I’m biased. I think books are great, especially children’s, especially children’s books, right. Are a wonderful way to, to just read with your kids and learn alongside your kids. Because again, you know, we, as adults are also learning and growing as well, we are usually the issue is not that there’s not resources out there.

Helen (37m 46s):

There’s usually plenty whether it’s a book, whether it’s a video, whether it’s YouTube, whether it’s a television series, there is, there’s so much out there. It’s usually just more about initiative and intentionality. So I think if Christian parents just are willing to take that intentional time to look and see what’s out there that would be age appropriate for their kids in their families, do some learning on their own as well, do a little reading up beforehand. Those are things that are anyone can do. I mean, there’s nothing hard about it. It really just is a matter of will and willingness to take the time to prepare and to learn.

Amy Julia (38m 22s):

Well, thank you. And I’m curious, I mean, this is, you know, just kind of coming to the end of our time. And we, as I said, you’ve got 10 postures in the book and not only do you have 10 postures, but then at the end of each chapter, there are a of, you know, a good handful of different practices and activities, many, many resources, just like you just answered as far as books and other ways for parents to be in conversation with their kids. I took away just even the watching the news together and then discussing it at the dinner table, just having various, I mean little things that can be incorporated into family life. But I’m curious if there are one or two practices that you as a family have really come to value when it comes to becoming race-wise one or two things that you would just leave us with as far as the things that have been helpful for you as a parent.

Helen (39m 19s):

Yeah, I think, And this it’s going to sound so basic. I wish there was

Amy Julia (39m 23s):

Basically because okay. Sometimes that’s all we can handle.

Helen (39m 28s):

Yeah. We, as a family during, especially this was during the pandemic, we actually spent most of our Sundays, you know, worshiping at home like many people did, but we actually did our own scriptural study as a family. And then of course, and at every single time of study with just open prayer and their prayer, such a great way, I think that we can not just communicate with God, which of course is the primary purpose of prayer. But it’s also a way that our kids can learn from us as parents as to how we engage with God on some of these challenging topics. So as, as you are praying out of the sincerity of your, your own heart lamenting things, you’re seeing on the news, naming some of the injustices and realities where you need and want to invite God’s justice terrain, expressing those moments of lament, expressing solidarity with those who are suffering.

Helen (40m 22s):

I mean, as parents, I think that’s incredibly powerful for our kids to hear us being willing, to verbalize those cries of our heart and soul in this particular area. And being able to acknowledge, you know, God, I don’t know what to do about this. Like, I don’t know what to do by this continuing injustice that’s happening against black and brown bodies or naming those realities. Like just being able to do that so that your, your kids can see the sincerity of your own journey. I think that is incredibly, incredibly powerful. So really the process to Becoming a Race Wise, Family starts with parents being willing. And we’ve used that word intentionality already, but just being willing to take that time, to open up their own hearts, minds and souls, because it’s not going to always be comfortable.

Helen (41m 9s):

It may actually be painful at points as you start kind of confronting maybe areas of your own bias or areas of your own ignorance or areas where, you know, you need to repent of certain things or you have to own and name your own privilege. As you mentioned, that said posture, we talk about in the book as well. So this is not a comfortable journey at times. It’s not, but what’s on the other side of that is the more we open up our hearts and our minds and our souls to the realities around us and where we can open up our eyes to see the injustices and be willing to name it and talk about it. The more our kids will begin to see the water more clearly, you know, around them. And that’s, I think super, super important, especially if you’re someone who is, you’re a family that’s growing up in the dominant culture.

Helen (41m 54s):

I mean, the world is changing. And so that water is going to change and continue to change in the future. The more you can be aware of it, talking about it, naming it, normalizing conversations around it and normalizing it in your prayer time. The more your kids will start to pick up on that and learn from that as well, but how to be race-wise themselves.

Amy Julia (42m 14s):

Helen, thank you so much for your time today. Thank you for your book. Thank you for your stories. I really appreciate it.

Helen (42m 21s):

Oh, it was my pleasure. Thanks for having me on Amy, Julia

Amy Julia (42m 28s):

Thanks. As always for listening to this episode of Love Is Stronger Than Fear. You can check out the show notes for more information and be on the lookout for one more episode this season, next time I will be talking here with theologian, John Swinton about health and DISABILITY and healing. I’ve already recorded that conversation. So I can tell you that you will not want to miss it. I was so blessed by that as always. I’m grateful to Jake Hanson for editing this podcast to Amber Beery, my social media coordinator. And I’m thankful to you for being here. So as you go into your day to day, I hope and pray that you will carry with you.

Amy Julia (43m 8s):

The peace that comes from believing that Love Is Stronger Than Fear.

[podcast_subscribe id=”15006″]

Learn more with Amy Julia:

- To Be Made Well: An Invitation to Wholeness, Healing, and Hope

- S5 E10 | How Kids Can Fight Racism with Dr. Jemar Tisby

- S3 Bonus | Talking with Our Kids About Race, Justice, Love, and Privilege

If you haven’t already, you can subscribe to receive regular updates and news. You can also follow me on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Pinterest, YouTube, and Goodreads, and you can subscribe to my Love Is Stronger Than Fear podcast on your favorite podcast platforms.