Note: This transcript is autogenerated and does contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Amy Julia Becker (00:05)

Hi friends, I’m Amy Julia Becker and this is Reimagining the Good Life, a podcast about challenging the assumptions about what makes life good, proclaiming the inherent belovedness of every human being and envisioning a world of belonging where everyone matters. Welcome to 2026, my friends. It has been quite a start to the year already. If you are listening in real time, which is to say early January 2026,

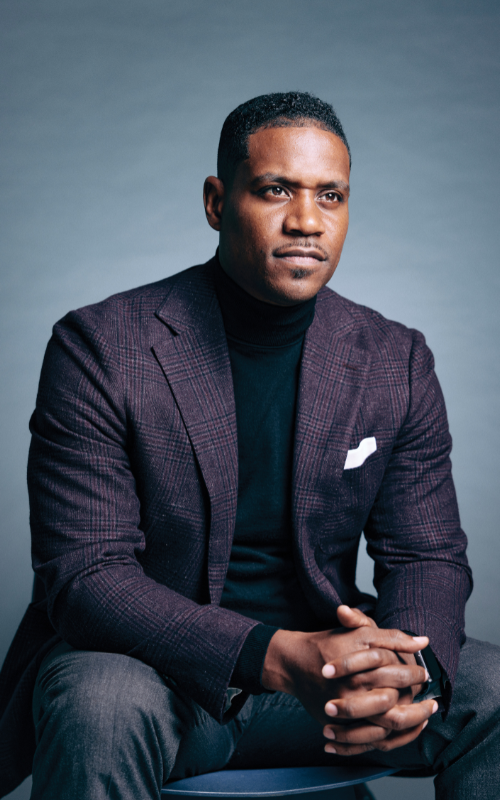

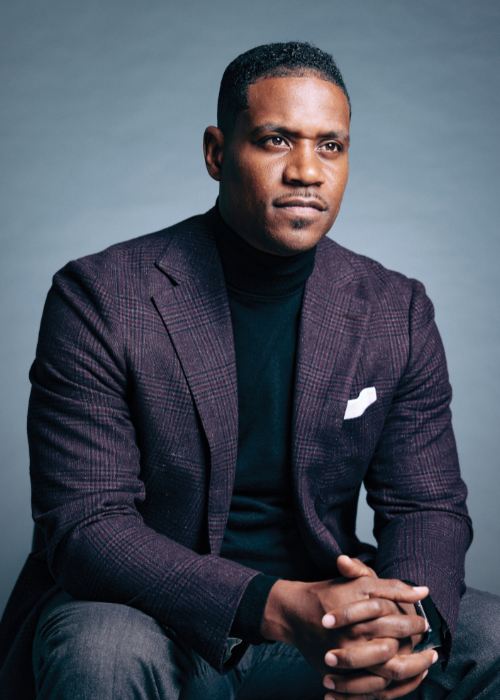

You know that the United States has arrested Nicolas Maduro, the president of Venezuela, and there’s a lot of international political instability that could lead to all sorts of outcomes in the months ahead. It’s very uncertain. On the domestic front, we continue to see high levels of discontent, political polarization and unrest. It is not an easy time, no matter where you fall on the political spectrum. And it is for exactly these reasons that I am so grateful for my guest today, Justin Giboney.

Justin is an author, an ordained minister. He’s an attorney and a political strategist. And he’s the founder and president of the AND Campaign, a Christian civic organization focused on raising civic literacy, promoting civic pluralism, and equipping Christians to engage politics with the love and truth of Jesus Christ. And if that sounds vague or abstract, then this conversation is really for you because he puts

Hands and feet on what I just said. Justin is the author of Don’t Let Nobody Turn You Around, how the Black Church’s public witness leads us out of the culture war. I love Justin’s combination of realism and hope when it comes to the public square. He is honest about the challenges we face as a nation while also offering an invitation to a faithful public witness. I hope you are as encouraged and challenged by this conversation.

as I am.

I am sitting here with Justin Gibeney and I’m so glad that we are getting to talk here today. Thank you so much for joining us.

Justin Giboney (02:08)

Amy Julia, thanks for having me. I’m excited about the conversation.

Amy Julia Becker (02:12)

Well, you have written a great new book and it’s called Don’t Let Nobody Turn You Around. I’m really excited to talk about it. In the beginning of the book, and then actually with this sweet photograph at the end of the book, you really pay homage, I guess, to your grandfather and your grandmother. So their names are Bishop Thomas L. Cooper and Willie Faye Cooper. And I wanted to just start with them. Could you tell us a little bit about your family?

and your grandparents in particular and how they shaped you and influenced your words in this book.

Justin Giboney (02:44)

Yeah, sure. mean, obviously some of my earliest memories are being with my maternal grandfather and grandmother. And I think for the family, they gave us just a foundation of faith, of belief in Jesus Christ and an understanding of his character. And so when I think of my foundation, I really do think of the lessons that they gave me. And, you know, they were part of the civil rights generation, which is a really big part of the book.

Yeah. And as I look at the polarization in our culture and in our politics, I think about the lessons and the principles that they had and how we might apply those today. And the more I started thinking about it, I began to realize they actually had some of those answers and we’ve lost those. But I think it’s a time for us to retrieve them.

Amy Julia Becker (03:31)

Can you speak a little bit to that, ⁓ the things that they had that we’ve lost when it comes especially to this idea of ⁓ being in the public square?

Justin Giboney (03:41)

Yeah, I mean, as we know, know, going both of those, both of them were from the South went through Jim Crow were raised by some people who actually had been enslaved. So they were aware of very tough and harsh situations. One of the things that always stuck out to out to me about them though, is they never were bitter, right? They didn’t come off as having a bitter spirit was I sometimes today, you know, somebody calls us a name or they say something we don’t like or we get insulted and we

you know, we just kind of fall apart and you know, our whole perspective is based, is dictated by how someone else thinks of us or talks to us. And I think because of their faith, because really survival demanded that they have a certain resilience. ⁓ that’s one of the things that, that really sticks out along with how they viewed themselves and viewed their neighbors in a much different way than we do today.

Amy Julia Becker (04:34)

There was one place in the book where you were writing about bitterness and you said, you know, it doesn’t have to do with your social position or the amount of power or wealth that you have. And you give the example of ⁓ King Herod being bitter and then Mary, who was essentially just a really poor and vulnerable young woman being able to sing praise to God and rejoice in her circumstances and the life that she was given.

I just thought that was such a powerful contrast, those two biblical characters, but as a way of pointing out what you just said, that there’s a resilience and attitude, like a posture towards the world that can come not from our material circumstances at all, ⁓ but from these very different places. And what you think that, like what shaped and formed your grandparents and what could shape and form us in a way?

that is going to enable us to live in that place of rejoicing and gratitude rather than bitterness.

Justin Giboney (05:35)

I think it’s the promise of the gospel, the understanding that God is always with you, He never abandons you, and even when you’re going through tough times, there’s meaning in those times and you glorify Him by having hope. And so one of the things that they always had was hope and also a belief in the redemption of even their opponent. So they believed

Today we can kind of come about it, whereas our opponents, if you do something really bad or have a really bad belief or hurt people, and sometimes that really does happen in real ways, then you’re somehow irredeemable or purely evil. That is not biblical. Although I may need to oppose you, I may need to make sure that you, you know, kind of are publicly, your ideas are publicly shot down and that some of the things you do, you’re held accountable for. That doesn’t mean that I feel that you as a person are irredeemable.

and can’t do good or that there’s something that you can contribute to my life. That’s a very different perspective than you see ⁓ in our public square today. And it all had to do with the faith and taking the words of Jesus seriously, love your neighbor, love your enemy. It doesn’t mean you let people get away with things that hurt others, but it does mean that you see their human dignity even beyond their insult.

Amy Julia Becker (06:54)

I so appreciate that and ⁓ I love that connection between these kind of ancient texts, which obviously as Christians we believe are still alive today, but nevertheless were written in a different culture in a different time that are kind of taken for both on this personal level, but also that lead to a different public witness. And I wanted to speak to that next because you’ve got this subtitle to your book, which has, I think, a promise embedded within it. So the subtitle is…

how the black church’s public witness leads us out of the culture war. And I want to talk about all of the ⁓ aspects of that, but I thought maybe we could start by just asking you to explain what do you mean the black church’s public witness? And you’ve already mentioned the civil rights movement, so we could talk more about that, but also, you know, the decades since then, what is the black church’s public witness?

Justin Giboney (07:46)

Well, I think a big part, so a public witness in general is your testimony to the world. What you believe is right and wrong. What you believe is a good and bad moral and immoral, right? This is through your words, but not just your words through your actions, what you believe to be true and who, and who you serve. ⁓ and, and because of a lot of the struggle that the black church and black culture just in general has been through, I think one of the primary

messages or the primary witness that we have given ⁓ America is one of hope and resilience and finding a way to push back against negative things or to push back against evil without becoming evil. Now, I want to be very clear. This book isn’t just an exaltation of the black church. In fact, it actually challenges the black church of today in ways that it actually has fallen short of that legacy.

And I also would say that, you know, the good parts of the Black church’s legacy belong to Christians in general, because this is all inspired by Jesus, inspired by the gospel. So I do want to make that very clear. ⁓ The question I’m really answering is how the civil rights generation as the crown of the Black churches witness, how they would react to the polarization of today based on the principles that they maintained in those ethnicities.

Amy Julia Becker (09:11)

I really appreciated you ⁓ repeating this here, but it’s also in the book that like this, the best of the black church is the best of its owned by or should be embraced by all Christians. This is not just a matter of the black church in particular, although it is also instructive for all of us, ⁓ black and white and all the others right now to be looking at what was it that actually enabled. And you do a wonderful job, not only of lifting up, ⁓

Dr. King, but so many other men, but also women of the civil rights era, and not just talking about what they were able to accomplish when it comes to legislation, but actually where that came from as far as that personal faith that really animated and kept them going the way they did. I thought it might be also helpful to ask, how is that public witness different than ⁓ progressive social justice movements?

that we see today. Because I think again, there’s some overlap, but there’s also some real distinctions.

Justin Giboney (10:16)

Yeah, and that’s a very good question. One of the reasons that I wrote the book is because I do think there’s been some revisionist history when it comes to the civil rights movement or just that public witness where you see conservatives try to co-opt it to create some colorblind movement that kind of fits their narrative. And then you see progressives make it less about religion and some of those in scripture and more just about social justice by itself.

And it was much bigger than that. So when I look at today’s kind of progressive activism or kind of just the social gospel, I think what it misses is the true belief that they had in the authority of Scripture and the whole counsel of God. So what that means is they thought that justice was very important, but justice alone wasn’t everything. You also had to be righteous.

You also had to understand the value of moral order and morality. So it wasn’t just about going against society and societal structures that were bad. It was also about looking in your own heart and seeing the bondage in your own heart from your own sin. And I think the biggest problem that I see kind of with progressive activism is that it can’t really reconcile individual sin because it sees kind of truth coming from the individual rather than coming down from.

from God. And that’s a major difference between the, you know, the, the civil rights movement and some progressive movements. ⁓ It impacts how they actually see freedom. It impacts how they actually see absolute truth. Because on a progressive side, a lot of people would say there is really no absolute truth. And my question will be, well, how do you, how do you tell somebody else to do justice? Because if I say, Hey, AJ, you have to do justice.

Well, that means that I’m giving you a unconditional standard that whether you agree with it or not or understanding it or not, you have to abide by it. Well, that means that it’s an absolute truth. And so those things go together. I think that’s why there’s some holes in the way I think progressives and sometimes even social gospel focused people engage with very important issues of justice.

Amy Julia Becker (12:32)

Yeah, and I love there was a place where you wrote the prohibition on hate was just important, just as important, if not more important than the command to do justice. like justice is a part of this broader ⁓ moral imagination, which we will get back to the idea of a moral imagination, but that was carried by these civil rights leaders and that there was that if we only are talking about justice, we’re actually not only going to reduce

what we’re called to in an unnecessary way, but ⁓ we might even allow ourselves into these postures of hatred or of cynicism. Like it makes it all too small. ⁓ And it also might again just perpetuate division and a culture war rather than actually being ⁓ a movement of healing for the entire culture.

Justin Giboney (13:22)

Yeah. People like Fannie Lou Hamer made it very clear that once you hated even somebody who was acting wickedly, you lost because at that point you disconnected your movement and your behavior from God. You can’t love God and hate your neighbor. and so I, we tend to think today that if somebody does something bad enough, if they, they question my human dignity or whatever we want to say at that point, I can cut them off and have contempt for them.

It was very clear. There was no question that that could not happen. And that’s one of the differences. We talk about the differences with kind of progressive activism, but I think that’s one of the differences with ⁓ black secular activism that this movement had that you had to maintain your righteousness and you had to believe in the redeemability of your enemy. You could not hate and insult and all those things. And I think even unfortunately in some Christian

engagement today, it’s become more secular than a reflection of that legacy.

Amy Julia Becker (14:26)

I find that even ⁓ so often there’s a lot of attention paid, I think back to like when Dylann Roof massacred a Bible study of ⁓ men and women, you know, I guess 10 years ago now in Charleston, maybe a little bit longer. And then there was a public witness of forgiveness offered by many of the family members of the victims.

And the way it was written about and still is often written about is that the forgiveness was for the sake of the people doing the forgiving so that they would not be bound by hatred to this young man. And there’s a truth there. But I think what you’re getting at is actually the truth goes a lot deeper than that and has to do with believing that he also is made in the image of God. And to not forgive is actually to go against something that is true about

all of us as humans ⁓ and that is bigger than just me feeling better and not being weighed down and held by unforgiveness. And I just often read the descriptions of forgiveness that I think is often born witness to in public by ⁓ various people, white and black, but I’ve seen it often through kind of the witness of black Christians. And I feel like that, again, it just makes it

too small what’s going on there. Like the forgiveness is not just so that I am okay ⁓ and I can be freed of hatred for this person, but actually so that I can image something of who God is in the way that I’m conducting my life. Does that ring true to you?

Justin Giboney (16:07)

Yeah, I think, I think it is, it is at very least twofold in that way. When we forgive somebody, it releases us from being bound by hatred or contempt for them. But it also recognizes that not even Dylan Roof, who comes into a church after being welcomed in and shoots everybody, not even he can make himself irredeemable. That’s a power, that’s a Testament to who God is and the Testament to how God sees us, but we have to practice it.

Because it’s way easier to hold him in contempt and to act like what he has done is unforgivable than to in this moment after your family members have been killed to actually say, forgive you at the hearing where he’s being sentenced. Now this isn’t to say he shouldn’t be sentenced, but I think a lot of people would say, well, if I say this during the sentencing, this might actually make them go easy on him. I’m not going to say that. That’s not the stance that they took.

Amy Julia Becker (17:06)

I really appreciate just bringing that deeper level of, ⁓ yeah, of no one is irredeemable and the hopefulness, but also the like, gosh, that is a really powerful and really, you got to really believe it to be able to live that out, to really practice that. Well, I want to talk about the culture war for a minute. We’ve talked about public witness, but the culture war also comes up in the title of your book. And one of the ways I think you

are one of the invitations of the book is a different way, a different way than this culture war left versus right, conservative versus progressive. And so I wondered if you could, ⁓ and you’ve done this already a little bit, but give us a few examples of how a Christian public witness might be able to just defy conservative versus progressive culture war issues.

Justin Giboney (17:58)

Yeah. Yeah. And so just to back up a little bit, if you don’t mind, just so people understand what the culture war is. The culture war is a fight between conservatives and progressives for the values of America, who will kind of dominate what America is about and what we value. So it’s been going on for a long time, probably starts in the twenties and it moves on from there. One of the things about the culture war that I think makes it so toxic

is that it is seen as ⁓ a battle between good versus evil. And once I have said that my side is purely good and the other side is purely evil, one thing that happens from there is I don’t examine my side, right? I can’t say that my side has done anything wrong because that would hurt our narrative. But what that means is that I become extremely dishonest and I allow my side to get away with things that it shouldn’t get away with. So let’s say honestly, my side is

right on seven out of 10 issues. Well, I may have a reason to lean that way, but on those other three issues, if I don’t call them out and if I’m not honest about it, then I’m not being truthful and I’m allowing people to get hurt because I just want to make sure that we win. And so I think one part of the Christian perspective is saying, no, no, no, my witness and letting people know what is right and wrong on all these issues, not just a few of them that fit with me.

is more important than winning. Now I’m a political strategist. I don’t ever strategize to win. I mean to lose, but as a Christian, I have to be willing to put my witness above this temporary win. That’s one of the major differences ⁓ that you see. But here’s the thing, because I think to a lot of people, the way of going about this in the civil rights legacy can seem kind of Pollyannaish.

But the truth is it was far more effective than a lot of the more belligerent ways of going about it that you see. Is it really effective to go out and call people names and tell them how stupid and evil they are? Or is it more effective to be like Dr. King and do the hard work of trying to persuade people who disagree with you, trying to inspire them to take another route? That’s hard work, but it’s actually more effective work than just going out and getting patted on the back from my tribe because I

came up with some quips that made the other side look smaller.

Amy Julia Becker (20:25)

One of the things you write is that in our contempt, we not only hate our opponent’s vices, but we also begin to hate their virtues. Many on the right can’t appreciate the work the left has done for women’s rights, and the left can’t appreciate the culture in some white evangelical circles of adopting children from all over the world. Like you just give these examples of ways that we not, I thought that was so interesting that we might not only hate each other’s vices, but actually our virtues as well. And so we

create these caricatures of the other side instead of engaging as real humans who have common human concerns. And again, we might really be right and wrong about certain things and there might be other things where we’re trying to just figure it out. We’re just trying to actually ⁓ achieve a similar goal and we think different ways are gonna get us there. ⁓ So I guess how do you think overcoming those types of… ⁓

dichotomies, like where does it start and how does it start?

Justin Giboney (21:26)

Well, it can’t just be about the scoreboard. The reason that we end up hating their vice, their virtues is because we can’t admit that their virtues otherwise are narrative that they’re purely evil would die. And so we have to let go of the pride that comes along with the culture war. ⁓ we have to have a, a, a level of intellectual honesty that says, even if the truth doesn’t seem to be in my immediate best interest, even if it hurts my narrative, I love the truth.

more than I love being right at this moment. And so I have to admit when they get something right, because that’s good. And otherwise I become exactly what I say that I’m fighting against. And so that’s where it starts. think it starts with humility, intellectual honesty, and again, a willingness to examine oneself. And let’s be honest, whether you’re on the left or the right, one thing the custodians of the culture don’t want you to do

is examine them and examine yourself and your tribe. And that’s where the boldness of all this comes in, that you have to do it either way and be willing to be misunderstood.

Amy Julia Becker (22:38)

I really appreciate all of that. I want to ask you a little bit, going back to the civil rights era, thinking about the advances that were made in the 60s and how there were these other, women’s rights was happening at that time in a different way than it had perhaps ⁓ before. You also had what is now called the sexual revolution. And I think in the way we think about those or taught them in school, they’re all of a piece, right? Like they are all… ⁓

Yeah, coming maybe even from the same source or the same types of ideologies and ideas. I’m curious how you see it. Like, do you see those as being kind of intricately related to each other or as like really separate movements that might have, you know, things that might be ⁓ able to be critiqued about them separately?

Justin Giboney (23:27)

Yeah, what they share is that often they were pushing back against the same ⁓ group. So I think, you know, your kind of traditional conservatism, you see the civil rights movement pushing back against them on race, you see women’s rights and others pushing back on them on based on other things. So there is there is that connection. But but in some ways, that’s where the connection ends. Because I think when you look at the sexual revolution and you look at

the civil rights movement, you have two completely different conceptions of freedom. One is a freedom for self-fulfillment, a freedom of kind of pleasure seeking and all those things. The other is more of what I would say is an Exodus, in the Bible, Exodus motif freedom, which is a freedom not just to do as thou wilt, but a freedom to worship God, a freedom to have the rights that God has given you.

to pursue God better, to pursue human flourishing. I don’t necessarily think pleasure seeking is the same as pursuing human flourishing. And that doesn’t mean that everything that had to do with those movements was wrong. Certainly not with women’s rights, but it came from a different route, had a different ethic and also a different ⁓ objective. And that’s what I mean when I think nowadays we kind of combine all of them as if they were coming from the same perspective. But if you actually read,

what people in the civil rights movement were saying, it’s not true. And in fact, when you see this split between white America starting in the twenties and beyond between conservatives and progressives, the black church is watching. If you read their, ⁓ you know, the denominational periodicals and things like that, they’re watching what’s happening, paying attention to what’s happening and commenting on it. And basically what many of them are saying is, I see this split, they’re going in two directions.

And we can’t follow either of those directions. Because if we go to the right, we lose our bodies because there’s no justice. If we go to the left, we lose our souls because they’re not following scripture and not trying to be righteous. This is what they’re looking at and saying. so for organization like mine, the and campaign, which really doesn’t go to the left or the right, think there’s different way to do it, a better way to do it. We’re coming from that route.

and from that observation of the beginning of the culture war.

Amy Julia Becker (25:56)

That is fascinating and I have not ever read those periodicals or known that piece of the history. Will you actually ⁓ tell us a little bit about the and campaign, which again, I’ve kind of followed for a while, but we haven’t mentioned it here and I think that listeners would be really interested to know more.

Justin Giboney (26:14)

Yeah, sure. So the ANCAMPAN is a Christian civic organization. And one of the main things that we want to do is we want to help Christians engage based on biblical principles and not the false binary of the culture war. So many people, when they look at politics, they feel like I have to either go to the left or I have to go all the way to the right. And that makes them uncomfortable because they see things wrong on both sides. And we want to say, that tension is good. We think that the left is sort of missing

the truth and convictions that you need to engage as a Christian. We think on the right, their mission, the compassion ⁓ and the justice in some instances that we need to do. And so we shouldn’t ignore that just to fit in with one side. We should have, as we would say, compassion and conviction. There shouldn’t be social justice Christians on one side and morality Christians on the other. All Christians should care about justice. All Christians should care about morality because they add our

they interact together. And when you don’t have ⁓ morality, you’re not going to have very good justice and likewise. So that’s how we come about it. The and literally means compassion and conviction, love and truth, justice and moral order instead of choosing one or the other. So that’s really what we’re about.

Amy Julia Becker (27:31)

And how does that like play out? Like what do you do, you know, with that, that and how do you do it?

Justin Giboney (27:39)

Yeah, so we put out a lot of content. So we have the Church Politics podcast that comes out every week. I write articles in Christianity today around once a month, just helping Christians understand how to apply the principles that we’re talking. We don’t want to just put principles out there. We want to help with the application based on things that are going on today. We also, for Christians who want to run for office or want to run campaigns, we have a cohort that we take them through, a 10-week cohort.

to learn how to better engage. A lot of Christians are interested in politics, but just don’t know how to really get started. And so we help with that. We ⁓ talk to pastors and other leaders about how to address issues from abortion to religious liberty, just tough issues that they may not know how to address. We want to really about equipping Christians to engage in a faithful way and also to have a respect for people who believe differently. So we talk a lot about civic pluralism to say,

Christians aren’t the only ones with good ideas. There are people who we may really disagree with on some serious issues that we still need to listen to and need to defend their right, defend their human dignity and defend their right to disagree with us as well.

Amy Julia Becker (28:51)

I love that. Thank you. Well, so I want to talk, as I mentioned earlier, about this idea of the moral imagination. You know, we’re in a podcast called Reimagining the Good Life, and I think a lot about the imagination. Could you explain what you mean when you say moral imagination?

Justin Giboney (29:07)

Yeah. Moral imagination is what keeps us from being captured or arrested by the moment. Moral imagination is the ability to see not just what kind of has been in the past, what’s what is in the present or what is likely to be in the future. It’s the ability to see what ought to be in the moment and what will be based on who God says that we are. So if moral imagination allows me to look at somebody who’s cursing at me and throwing insults and not hate them back.

because I see something bigger. It allows me to be in a very polarized and toxic moment and not be polarized myself because I’m transcending the moment while still dealing with that. And I think that’s one of the greatest attributes that ⁓ Christians can have is the ability to see past what’s going on. Cause any moment at any given time, and we see this, there’s always something that that particular moment is hiding from you.

And people can get really hurt if there’s not an agent in society that’s saying, hey, this isn’t all there is, we’re missing something. We have to see that there’s more than just what’s in front of us in the moment. And that’s what moral imagination is about, not being captured or not allowing the circumstances to dictate who we are, making sure that it’s our values and our beliefs that dictate who we are.

Amy Julia Becker (30:34)

So what does it look like to cultivate a moral imagination? What are habits or practices or ⁓ ways of thinking and seeing that are going to actually allow us to get into a tense and intense moment and transcend that in some way?

Justin Giboney (30:52)

Yeah, I think it’s forcing yourself to see the redeemability in others. I mean, that’s one of the major things forcing yourself to say, as bad as this looks, how can I look at this group of people and find something that I can learn? Is there a virtue there that I can capture, which I can allow to say, okay, it’s bigger than just how they’re approaching me right now. Right? Again, this does not mean having a more imagination does not mean I don’t hold people accountable. Here’s one of the strongest things about the legacy that we’re talking about.

is they had tenacity and grace. And sometimes we think in order to be tenacious, in order to really fight for justice and fight for what’s right, then we can’t have any grace. It’s just not true. And it’s actually more effective. What grace does is it, I don’t just want to defeat you. the highest goal is not to destroy you, it’s to redeem you. And I think that’s the key to it. So I think looking at others and refusing

to be hateful, refusing to reciprocate some of the things that they push on you is an exercise that builds moral imagination.

Amy Julia Becker (32:01)

What are the influences right now in our culture that are going to deform our moral imaginations?

Justin Giboney (32:09)

That’s a good question. With social media the way that it is, I think we have what’s been called, and this isn’t the term I made up, but I think it’s very helpful, ⁓ conflict entrepreneurs. Conflict entrepreneurs are people that have made an industry out of the division. And so they benefit when we cut other people off. They benefit from us wanting to hear the worst things about other people and justify everything that we do.

And if we keep listening to people who are always pointing out the worst of other people, always showing them as characters, you know, always kind of, ⁓

mocking them, you the Bible talks about scoffers, then eventually you do start hating your neighbor. You start thinking your neighbor is every bad thing that somebody that looks like them has possibly done. And that is extremely dangerous. So I think what one of things I’ve been telling Christians to do is be honest with yourself, go over your social media.

and start identifying the conflict entrepreneurs that you follow. These are people that are only really going to say good things about your identity group. Anything else is going to be negative, especially about the people that they see as your opposition. Those people are not healthy. They’re not being honest. They keep you enraged and you should never trust an influencer or leader that keeps you enraged. trust, you trust influencers that inspire you.

Because the ones that keep you in raise are going to get you to the point where you look at people in the wrong way or you do something that you’re going to regret.

Amy Julia Becker (33:52)

That’s really helpful. I think so much of, know, again, social media can be certainly used for good, but the ways in which it can also, as you said, like capture our attention and ⁓ also disassociate ourselves. I mean, I’m just so struck when I post something that is ⁓ for whatever reason, politically controversial at the ways people who don’t know me respond.

as if I am not a human. I mean, just like as if there’s no personal story, as if there’s no interaction. Because most of the time, if I’m posting something online, it’s only going to people who do know me because they followed my work for a while. And then every so often, usually if it’s political, it tips. And it’s like, there are 200,000 people seeing this thing. They clearly don’t know me. And that’s when I start getting these really, really contentious.

usually kind of thoughtless and mean statements coming back. And it just shows how easily that can start to happen. That sense of like, ⁓ I don’t have to really think about the other human on the other side of this, which I think goes back to just what you were saying before about like, we have to like practice believing that other people are redeemable. Like that there is something good to be seen and attended to ⁓ rather than

simply the caricature or the flattening of who they are, ⁓ where I get to demean their point of view. ⁓ And yet to your point also, like standing strong in saying, no, that’s not right. Doing both of those things just is, I think, increasingly difficult in our social media universe right now.

Justin Giboney (35:42)

Yeah, it’s speaking the truth in love. Ephesians four says we should be able to speak the truth in love. Right. And that’s a big deal. One other practice that’s helpful is when you’re listening to somebody you don’t like, even people who are wrong and they may very well be wrong. Most people aren’t purely malicious. So there’s some good that they’re trying to get at. may, you may disagree with their conclusion and how they’re getting there, but I think it is important to be able to identify what that good is and articulate it.

until you can do that, you can’t really have a constructive conversation with them because you, don’t understand what they’re trying to get at. And then the other big thing is not for not forgetting that people are all just going experiencing the human condition. So the person that looks mean or that’s tearing you down, maybe they’re just handling the bad things that are life the wrong way. I mean, these people are dealing with addiction. They’re dealing with abuse, abandonment, all the things that all of humanity deals with.

And when we cut that off, when we stop recognizing that they’re dealing with that too, it allows us to treat them in ways that, that, honestly cause tragedies.

Amy Julia Becker (36:54)

Yeah, I really appreciate that. And it is something that I have found when I’ve been able to engage with people in these kind of contentious moments. If I can say with sincerity, thank you, or I appreciate, you, you know, like that’s a helpful corrective about something that they’ve said. And then say, and here’s why I disagree about this other thing that it often does humanize the whole exchange. It’s like both of us become

a little bit more able to see each other. And that’s obviously on a very personal scale, talking about what you’re writing about, I think on a much broader scale, although, you know, we all are interacting with each other mostly as individuals, not as these, you know, we think in terms of these big groups, but then we actually have conversations one-on-one ⁓ with each other. And so if we can’t do that on an individual level, we probably can’t do it on a group level either. Which I guess brings me to, ⁓

I only have a couple more questions for you, but one is just, you know, for people like me, white Christians who are wanting to live in this place of more in the and campaign way than in the polarized way, ⁓ you know, but I do come out of ⁓ both white mainline and white evangelical churches. The ⁓ church we’re in now is slightly more ⁓ culturally diverse than, you know, where I’ve been for a lot of my life.

But I don’t have the backing of like the Black church tradition other than what I have visited or read in books ⁓ and have been really grateful for as a Christian, the witness of the Black church for sure. But what do you say to people like me who want to be engaged in a redemptive way in politics? And yet also, again, I don’t have that ⁓ same foundation as far as my…

family and the elders and the people around me who’ve had this like strong public witness. I’ve only been able to, yeah, kind of see it from afar or read about it in books.

Justin Giboney (38:57)

Yeah. Well, in addition to reading the book, because I do really think it is helpful in connecting you with the history. Because one of the problems that I think many white evangelicals have had is an inability to really reckon with and accept that history. That’s the first part. And I’m not one those people that says once you read it and understand it, you have to feel terrible about yourself for the rest. That’s not what it’s about. And that’s not the spirit of the civil rights movement. That’s more of a secular

Point of view. I want you to know it. I want you to try to process it, pray on it, and then try to connect with people and build relationships from there. Just because somebody’s a black Christian doesn’t mean that they get the legacy and that they’re really, you know, prayed through it and process it either. At the end of the day, it’s about us trying to understand each other and the best parts of our traditions and our religion and trying to

make sure that others see it. something else that I think is incumbent upon all of us is when those around us get it wrong in a gracious, but you know, a firm way to say, no, this is not how we should look at it. This is not how you should treat people because people have suffered and will continue to suffer if we do. That’s really important to do as well. So it’s the awareness, the acceptance of the history and then moving forward.

trying to fix things, whether it’s volunteering, it starts with relationship, but goes into actually doing the work, which is the fruit of our faith.

Amy Julia Becker (40:32)

Which kind of leads me, I think, to my last question, which is what happens in us and through us if we live out of a moral imagination that is shaped by God’s Word and God’s promises? And so I’d love to just hear from you, like how you’d respond to that and just essentially like, what is your hope in terms of the work that you do?

Justin Giboney (40:56)

My hope is that we would see the circumstances differently, that we wouldn’t be, as I talked about, arrested by the circumstances, that we would see our brothers and sisters in Christ differently. ⁓ Even when they have an opinion we disagree with, we might have more patience. Also see our neighbors differently. But really that the church would be able to rally around this legacy that belongs to all of us to engage in a better way. To say, yes, you know,

Conservatives and progressives in the world can’t get along, but Christians on both sides of the aisle can because we have too much in common and the world needs to see us do it. And so be willing to put aside our differences, examine ourselves and our tribes to come together in the unity that God has called us to come together on. ⁓ I think we’re getting too close to a place where we’re giving up on each other and that’s never an acceptable outcome.

Amy Julia Becker (41:53)

Thank you for the work that you are doing. ⁓ You’ve certainly done in this book, which I’ll say the title again, Don’t Let Nobody Turn You Around, but you’ve also are doing it in ongoing way through the And campaign. ⁓ And yeah, the Church Politics podcast, which I listen to. And again, for any listener who is listening here, I think one of the things you do there so well is that work of the And, right? The compassion and critique and… ⁓

and all the things we’ve been talking about. So ⁓ I hope that many people will just continue to follow along ⁓ and get some of the practical ways that we can all be living out of a different way because I think so many of us are really, really hoping and ⁓ needing that.

Justin Giboney (42:40)

Thanks AJ. I appreciate the opportunity and enjoyed the conversation.

Amy Julia Becker (42:45)

Thank you.

Thanks as always for listening to this episode of Reimagining the Good Life. If you want to learn more about Justin’s work through the And campaign, check out his book, check out his podcast, the Church Politics podcast. You can go to the show notes for links. His voice is a great one to carry with you into this new year. I also have an announcement to make. If you are a regular listener to Reimagining the Good Life, you’ll know that this podcast usually releases more or less all year round, except during the summer.

But for this season, we are going to only release one more episode. So I will be talking with Makoto Fujimura about his latest book, Art Is a Journey into the Light. That will be the final episode of this season. And then I’m going to take an extended break. And the reason I’m doing that is to work on my other podcast, Take the Next Step. So a couple of things. First, please stick around for that conversation with Mako.

Second, if you are interested in staying in touch during the pause in this podcast, there are a couple of ways to do that. You can certainly follow Take the Next Step, the other podcast. That will be released weekly. ⁓ And you also could sign up to receive my weekly Substack newsletter. That’s another way to stay in touch. And I would love to be in conversation with you. Again, show notes will give you links to do all of those things. Third, thank you for being here.

Thank you for listening. Thank you for sending me your thoughts and comments along the way. It means the world. I really love having these conversations one-on-one with my guests, but I also love having the conversations with you, the listeners. So thank you for that. And finally, I want to thank Jake Hansen for editing the podcast and Amber Beery, my assistant, for doing everything else to make sure it happens. I hope this conversation helps you to challenge assumptions, proclaim the belovedness of every human being, and envision a world of belonging.

where everyone matters. Let’s reimagine the good life together.